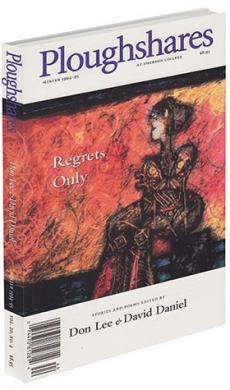

rev. of Igloo Among Palms by Rod Val Moore

Igloo Among Palms

Stories by Rod Val Moore. Univ. of Iowa, $22.95 cloth. Reviewed by Don Lee.

Selected by Joy Williams for the 1994 Iowa Short Fiction Award, Rod Val Moore’s

Igloo Among Palms proves to be a highly original and engaging collection. Set in dusty towns on both sides of the California-Mexico border, the seven stories are peopled by odd, refreshingly innocent characters who daydream of change, but feel doomed to inaction and inconsequence.

Tod, delivering dry ice to a supermarket, encounters a hitchhiker and a teenaged girl, both of whom end up having more romantic potential than Tod could ever imagine for himself. Tyrsa, a Mexican schoolteacher, impulsively sneaks across the border and accepts a job as a housekeeper, then tries to rescue the daughter of a door-to-door evangelist. Catalina’s parents own a motel in Mexico, where her mother’s hobby is découpage, pasting magazine cutouts onto plywood to make clocks, and where her father, a Peruvian weight lifter who insists on being called The Inca, drives around town with speakers on top of his car, broadcasting advertisements. Claudette and Tina decide to move in together, only to discover, after a bat drowns in their swimming pool, a basic incompatibility. Brad and Tyler, students at India Basin College, set out for Mexico on a marijuana-induced lark, but get stranded at a campground, where they are convinced to sell their plasma.

Not all of these stories are entirely successful as individual pieces, but collectively they build in power. Moore’s language is lyrical and at times incantatory, and he has a true gift for the comic and bizarre, creating a primeval but beautiful desert landscape in which misperceptions lead to whims and a desperate desire not to squander opportunities, exemplified in

Igloo Among Palms’s best story,”Grimshaw’s Mexico.”

Covering roughly twenty years, the story first shows Grimshaw, a police sergeant, driving his wife to a clinic in Baja for allergy treatments. Intent on exploring the town and taking in the culture, he instead falls asleep, and upon awakening, finds that his six-year-old son, Timothy, playing baseball with some Mexican kids, has miraculously learned to speak Spanish with near fluency. However, Timothy grows up to be an academic disappointment. Grimshaw encourages him to make a sheet-metal skeleton for a high school science fair and ultimately, pathetically, takes over the project. Later, after retiring from the police force, Grimshaw returns to Baja with his wife. Sitting in an outdoor café, he watches an old man with a battery demonstrating his ability to withstand the electricity fed into two rods he holds in his hands. Suddenly, Grimshaw stands up and grabs hold of the rods: “Here at last, he thought, squeezing the metal, here was the chance to do as Timothy had done, to play some Mexican baseball,

to learn to speak Spanish in a moment, and he waited for the furious shock that would stand his hair on end, turn his body transparent, as in a cartoon, to show the glowing, aching skeleton underneath.”