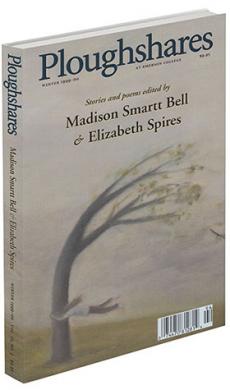

rev. of In the Surgical Theatre by Dana Levin

In the Surgical Theatre

Poems by Dana Levin. The American Poetry Review, $14.00 paper. Reviewed by Susan Conley.

Dana Levin’s first book of poetry,

In the Surgical Theatre, resonates with the dual imagery of pain and healing, scalpel and angel. The poems move swiftly and seamlessly from the literal drama of the operating room — its stark lights and surgical knives — to the larger domestic theater of family abuse and emotional bloodletting. Winner of the inaugural APR/Honickman First Book Prize, selected by Louise Glück, this fiercely intelligent book is grounded firmly in the realm of American confessional poetry, but Levin wisely and skillfully manipulates conventional boundary lines.

The “future of the body” is in question here, and the rich symbolism of this corporeal and spiritual investigation supports this volume in a complex architecture. Lines between truth and fiction, history and autobiography, continuously blur in the book’s dark, elliptical explorations, where we see “the limbless, the fractured, / civilians and factions / spilling out of its cornucopia of grief and divide”(“First Cradle”).

“On February 9, 1965 I was slit through the belly / without anesthetic,” the speaker of “The Baby on the Table” flatly declares. The poem then demands of the reader, “Have you ever been hurt, have you ever been cut, is it only / physical knives?” Earlier, in “Body of Magnesia,” the speaker asserts unequivocally, “I was solid, I hurt, my wings could be broken, / it was joy, I was living in it, I bled, I cried.” Clearly this collection is not for the squeamish or faint of heart. Levin’s gaze is unflinching, and the reader is implicated and challenged at every turn.

In the collection’s title poem, the disembodied speaker watches her father get cut down the middle and asks of the wound: “Do you want it to be stars, do you want it to be a hole to heaven, / clean and round?” The speaker then ascends to the realm of angels to watch the ensuing performance: “I came up here, to the scaffolding above / the surgical theatre / / to watch you decide. / Can you go on with this mortal vision?” What amazes in this collection is how various speakers hover over bloody bodies, over wreckage of nuclear families and inconsolable anger, and still choose to go back into the body because they “can’t bear not feeling” (“Door”).

A patriarchal father figure storms in and out of poems like a tornado: “And then we were in the cellar, / in the darkness with the jam jars, while he roared and tore past our doors” (“Wind”). The speaker is so disgusted with her father, “his sagging face of an idiot / struck dumb by grief,” that she won’t talk to him. Just when these themes of domestic revenge and hate feel too familiar, Levin broadens the agenda to include transgressions of a global scale: “the medics, the nurses, the mothers and fathers, generals and presidents, / hovering above the stink of ripeness and death” (“Personal History”).

Levin’s syntactical innovations are impressive: the lines sprawl and roam over the page, and then become tight and internal, almost as a defiance to convention. Enjambment speeds the poems up and helps in the difficult task of weaving the vast surgical metaphor from stanza to stanza. Yet, it is often the device of the angels that holds these disjunctive, wildly disparate poems together. Much is asked of these harbingers of life. Angels instead of surgeons handle the scalpels in the title poem, presiding over the sick, “perched quietly / on the rib cage . . . on either side of the hole like handles / round a grail . . .” They work furiously behind the curtain to “cocoon you, / to give you a stage . . .” Like Rilke’s angels in the

Duino Elegies, Levin’s angels know pain and despair, but ultimately they are transcendent witnesses who give this fine book its wings.