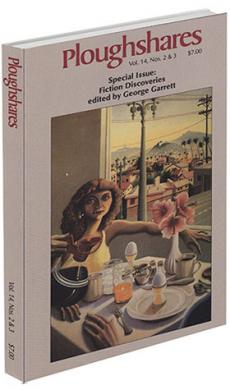

R.V. Cassill’s Clem Anderson

I first read this tremendous book in 1961, when it was published, and recently read it again after an interval of twenty-six years. Both times it has struck me as the best novel I know on the subject of writing, or on the condition of being a writer: and that alone seems marvelous because so many other novelists have found only embarrassment in the same material.

Even the most faithful readers of Thomas Wolfe must sometimes wince at his rhapsodizing about Eugene Gant's genius; even the most abject admirers of James Joyce might wish he had confined his tone of special pleading for Stephen Dedalus to

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, where it belongs, rather than letting it spill over and weaken whole sections of

Ulysses. But Cassill's central character is thoroughly convincing all the way: Clem Anderson is a writer in his blood and bones.

He isn't very nice. He is arrogant, irresponsible, overly remorseful and self-lacerating. He hardly ever stops talking (in the Army he's called "Open-throat Anderson"), and often says one thing while meaning another. People who love him, or try to, must always allow for his dark moods, his reckless drinking and his "demons"; perhaps his only consistent virtue is the purity of his belief that he is the only writer in the world.

Anderson's life is short — he will go terminally crazy and destroy himself at the age of forty — but it makes a very long story as told by Dick Hartsell, also a writer, who has been his closest friend since their university days.

The novel is divided into six parts, each with a flexible narrative pattern that can take the reader back and forward in time without depending on strict chronology, so that the whole of it is made to evolve in the effortless richness of memory. And it seems to me that the author has chosen exactly the right beginning for the book: a point when Clem Anderson's career is almost finished but nobody knows it yet.

The year is 1953 and the place is a Midwestern college where Dick Hartsell, now settled as a teacher and family man, has arranged for Anderson to come out from New York as a guest lecturer. Anderson is thirty-seven and apparently going strong: his highly regarded books of poetry and short fiction are behind him; he has published a successful first novel, though he regrets having allowed his publisher to make substantial cuts in it, and he is currently revising his first play in readiness for a Broadway production.

He is drunk on arrival in the college town and brings the young Hartsells some sharply upsetting news: he has broken with his wife Sheila, of whom the Hartsells have long been as fond as they are of him, has left her and their two small children, and now plans to marry a celebrated movie actress named Susan Hunt.

It is a troubling visit for the Hartsells' eleven-year-old daughter, too. Her parents have told her that collecting semi-precious stones is an "important" thing to do, but today there is so much baffling, impenetrable grown-up talk around the house that she feels her collection is mocked and ignored; she throws all her stones away into tall weeds and angrily turns on her father. "I only want to get it straight once and for all," she tells him. "What's important and what isn't? Once and for all you'd better tell me. You'd

better!"

At home again that night, after taking Clem to his train, Dick finds his wife constricted with grief over the Andersons' divorce, if not over the terrible uncertainty of life itself.

"I want to howl!" she says, and he can't console her. All he can do is turn away with a silent, eloquent cry of the heart that seems to sum up the helplessness of every husband and father:

Oh, my ladies, my darlings, what are you going to have

of us? That once and for all we tell you want is

important and bide that guess out to the end of time?

Early in the next section, Hartsell sifts though a great many pages of manuscript that were sheared away from the published version of Clem Anderson's novel as being "too autobiographical," and so we're permitted to read of Clem's early life in Clem's own words. These pages, amounting almost to a novel-within-a-novel, present a thickly textured, evocative story of rural Midwestern small-town life and of a troubled boy growing into a rebellious, precocious adolescent (at fifteen he impregnates an older girl who is sensible enough to arrange an abortion without his help). We learn a great deal about Clem Anderson and where he comes from, with ideas and images that resonate through the rest of the story — and we no longer have to take it on faith that he is a writer of uncommon brilliance.

Back in the more familiar cadences of Hartsell's voice, we follow Clem's eccentric progress through a big state university — his falling in with a scrappy literary crowd and soon becoming its most admired poet; his love affair and engagement to Sheila; then his reluctant involvement, with most of his generation, in the Second World War.

Clem's personal war in Europe is brief: in his first spate of combat he does very well as a soldier and is promoted to sergeant, but he must later spend twelve weeks in an army psycho ward — our first sign that his lifelong craziness can have clinical consequences.

During the early postwar years, as young married men, the two writers pursue their varying ambitions-and their lives continue to touch at many points and in several places. The action centers mostly around New York but there is a tense and disruptive summer in Acapulco, then a long season in Paris, where Clem accomplishes more in the way of serenity and daydreams than of writing.

On returning to the States for work on his play, Clem agrees first to participate in a summer writers' conference in Kansas ("it smelled like home out here") — and in that prosaic setting, overstimulated by admiration and alcohol, his nerves and mind begin to unravel. His eager group of students refer to themselves as "disciples" and tell him they've been "crying in the wilderness and predicting that the Second Coming is at hand."

Holding seminars every day in a local bar, he enthralls "his people" with an endless flow of poetry, of literary discourse and literary nonsense. Once, asked if he is "on his way to the Cross or to the asylum," he answers, "Presumptuous of me to say I am on my way to the Cross. But if that is the will of things, tell it in Gath and Ascalon that I was seen to be dragging my feet."

An impressionable girl named Marianne Luce goes happily to bed with him, and later says, "I'll love you forever" — a promise she will keep until the end of his life.

But Clem develops a more compelling attraction for a frivolous young married woman who entices him drunkenly into the acreage of a game preserve one night, then thwarts all his carnal advances ("I thought I wanted you," she said in the voice of a tragedienne, "but Clem, we're both married").

A sane man might have been able to dismiss this woman as a tease, but for Clem she has become the "shadow of a merely substantial woman projected by his desire on some cloud bank beyond the world. Futile to try to embrace this projection, and yet a man would be a damn fool not to try. What can the human heart love as much as the projections of its own desire?"

Wandering alone and rejected in the game preserve that night, he endures a vivid, elaborate hallucination:

Something more than moonlight illumined them

as, two by two, the animals came to take their prearranged

places on the stage of the clearing. . . .Along

with them came all manner of exotic creatures. . . .

Bengal tigers and arctic bears sat down. . . .Lions with

goat heads, dragon-winged horses. . .Hippogriffs and

unicorns and combinations never named came padding

softly to their places. And waited.

After them came figures like Egyptian statuary,

yet obviously of flesh. There were among them hawk-headed

females with human bodies, cat-headed ones

with an etched filigree of whiskers. . . .In order of

appearance that suggested greater eminence came the

holy baboons with snaky, trailing phalluses. They

looked blue-green in this light, as if carved from some

blue, translucent stone. Yet they were flesh. All these

waited too — the great lords of what the imagination

has conceived to be the animal kingdom, more wondrous

in their combination of animal features with

human than a simple human would appear. . . .The

order of their appearance suggested that a place had

been left open. Clem knew they were waiting for the

King to come.

In a modulation of light the Great Bride appeared,

essentially human in form. . . .And the Bride

was big. She must have stood twice the height of an

ordinary woman, a giantess superior in every way to

the beasts. . . .Something, like a voice speaking

from outside Clem's mind promised that the King

should be among them and the harmony of ritual

begin.

. . . In a moment, when all the spectacle faded,

a transcendent guilt seized Clem. It same as an indistinguishable

component of the knowledge that he was

not going to be allowed to volunteer as King. . . .He

had known what the King must be. And that was all.

It is not quite all. A few days later the young woman's husband arrives at the writers' conference and beats Clem Anderson senseless in a jealous rage.

But even after his recovery, when he is home with Sheila and the children again, the vision of the game preserve continues to haunt him as the genesis of a long new poem he now feels he must write, which he plans to call "Prometheus Bound."

"In a deadly serious caprice," Hartsell tells us, "he set out to create a new barbarism, destructive and self-destructive, from which alone, he believed, might come the language for the great new poem that demanded his services."

This is the period of Clem's career when he is expected to be working on revisions for his play, but he confides in a letter that he's "now doing the play with my left hand."

It is also the time of his breaking up with Sheila and pursuing Susan Hunt, the movie actress. "Susan would throw the same shadow of Collective Woman on the air for him to run at and try to embrace. In fact. . . .hadn't the projection of her shadow been effectively and materially accomplished by the wondrous Hollywood machine?"

When Hartsell visits the newlyweds Clem and Susan in their luxurious apartment, he is surprised to find that Susan is a likeable, simple girl — surprised too, and dismayed, to discover that Clem intimidates and bullies her in ways that Sheila would never have tolerated.

"The difficulty," Clem remarks in a letter to Marianne Luce, "of course presents itself when the lights are out on Susan and me. I rather miss the rest of the audience and the smell of popcorn, but it is some comfort to know that I am frustrating the desires of millions when I am unwilling or unable to do their office between her sheets."

Clem Anderson's play, meanwhile, has been so many times revised to suit real or imagined commercial requirements that it emerges finally as a "well-made" little drama that fails expensively after a token Broadway run-though it is quickly sold to the movies in a deal requiring Clem's employment as its screenwriter.

While on a Mexican vacation from Hollywood, Susan Hunt dies suddenly of an ectopic pregnancy — and Clem, who seems scarcely to grieve for her, quits the movie studio at once to go back to New York and devote himself wholly to his poem.

Marianne Luce, the Kansas girl whose love of Clem has by now withstood an unsuccessful marriage of her own, decides at last to visit him in New York and stay with him there. But she is terribly disappointed. Clem has become an almost completely idle man, forever talking about "Prometheus Bound" rather than writing it. He lives surrounded by people she considers worthless: other admiring girls, rich women. "old business associates" and literary parasites. Within a few days she is able to define him accurately as "an alcoholic liar," though he is still capable of talking "with incredible sweetness" — and very soon after that he is dead, in squalid circumstances.

Dick Hartsell is commissioned, by the editor of a weekly book review section, to write "an extensive critical memorial" for Clem; and he accepts the assignment but finds himself stymied in draft after draft of it. When the article appears in print he knows it's not right; then a friend suggests that he "write it as it was and take your chances," and so he sets himself the task of writing a novel to be called

Clem Anderson.

Reading the book again after so many years, I have found it holds up beautifully. It's as overpowering a story as I'd remembered and as funny a story too, in parts, for all its tragic structure.

And this second reading has brought new rewards in a greater understanding and appreciation of Dick Hartsell. Like Conrad's narrator Marlow in

Lord Jim, or like Fitzgerald's Nick Carraway in

The Great Gatsby, Hartsell serves as far more than the author's instrument for telling the story. He is a character who gathers philosophical momentum through the course of the book.

It seems relatively easy for Hartsell, along the way, to acknowledge that his friend was mad. Here, though, in his summing-up, he lets us in on a more difficult admission:

It came to me that the issue in my friendship with Clem

had always been whether I could be just to a man I

knew to be my superior. I had trembled often enough

to think that efforts at justice would only reduce him to

my smaller measure. Now, with his death, justice had

been given its classic sanction to look back along the

tracks of memory for the noble content of a life not at

all comprehended by its shabby end. . . .For a while,

I fell into the habit of thinking Clem had been as great

as he might have been. But that was not quite justice,

either.

So at last I prefer to rest my appraisal of Clem as

an artist on the poem that was never written. . . .

Irrationally I believe in it, but I am not so distracted

as to affirm its existence. . . It is uncreated,

though the very nature of Clem's fall created the conditions

for it. . . .

I have had intimations, thanks to him, of what a

man may endure of the self-knowledge that nature

seems to forbid us, and if my faith in that still unknown

plowland of dreams were to mean my exile from

reason itself, I would have to pronounce myself irredeemable.

It is my duty to teach those whom I can that

though the word may fail us, beyond the word is the

word. The fact may fail us yet again, but beyond the fact

is the fact. The Promethean legend is true enough. The

legend lives our lives, and it ends truly in a bondage

cruelest for those who dare most. The vulture and the

worm and the cliff overlooking the empty sea are not

inventions but heritages, and the grief of the hero who

risks them cannot be diminished or increased by the

acclaim of any public we know how to define. . . .In

describing [Clem's] bondage to the unreliable word, I

have accepted my own deepest commitment to it and

to all the humiliations we must suffer from time and appearances.

And yet by writing at this length — too long, not

long enough — I have made some progress from grief

toward the conviction that the bondage may be joyful

enough for the creatures we are.

Dick Hartsell's voice, it seems to me, is that of a man we can trust. It may even be a voice able to tell us "once and for all, what's important and what isn't — and to bide that guess out to the end of time."

It's only the voice of a character in a novel — but without it the novel might never have been worthy, in wisdom, of its author.

R.V. (Verlin) Cassill has published many novels and collections of stories over the years since 1950. When

Clem Anderson appeared in 1961 it won general acclaim as the author's first "major" novel, and its hardcover sales were substantial. Then four successive paperback editions kept the book alive until the midseventies; but the last of that series, with its tiny typeface and trashy-looking covers, was allowed to go out of print almost fifteen years ago.

Plainly, the time is long overdue for a new publication of Verlin Cassill's masterpiece.