Seven Urns

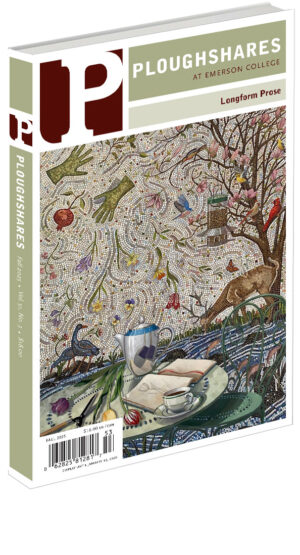

Issue #165

Fall 2025

Subramani knows there’s no getting around phoning Coleridge’s family now that he’s dead. She tastes the sour truth of it almost the moment the call informing her of his death disconnects, right after that little click like a scolding aunt,...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.