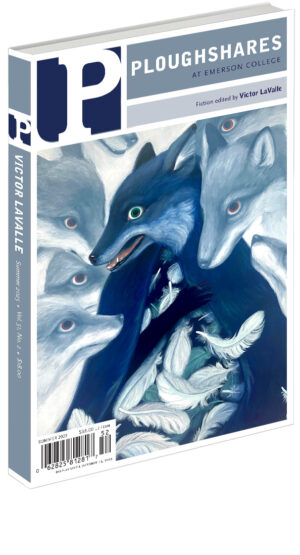

She No Longer Fears Him

Issue #164

Summer 2025

Rochelle isn’t exactly sure where to start or what to Google. “Male prostitutes”? “Male escorts”? Do people still say “prostitutes” and “escorts”? She types “male sex workers” in the search bar. The results include a Wikipedia page; an Out magazine interview series...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.