The Bet I Won

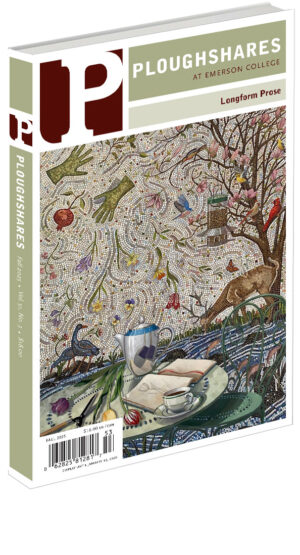

Issue #165

Fall 2025

When I returned from the front, I took the most direct route to the hotel room that Cora, the preacher’s daughter, had booked for us. No, that’s not one hundred percent true. The taxi stopped at the marble stairs leading...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.