The Woodcutter’s Daughter

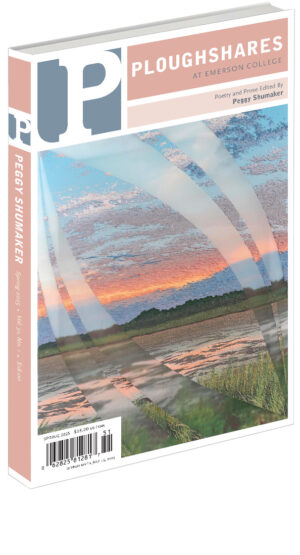

Issue #163

Spring 2025

For as long as I can remember, my mother wanted to get back home. She delighted in many things (Elvis Presley, migrating birds, black raspberry ice cream, figures of women and birds sculpted from stone) but for eighty of the...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.