Uncle Jimmy

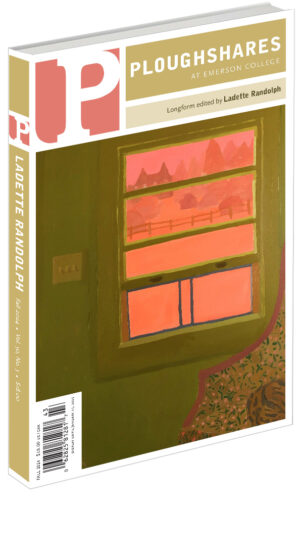

Issue #161

Fall 2024

Janelle is my oldest friend, but the word “friend” is outdated. We are sitting in a diner that smells of old oil and toxic cleaning solution. My personal chef prepared a salmon benedict an hour before we got on the...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.