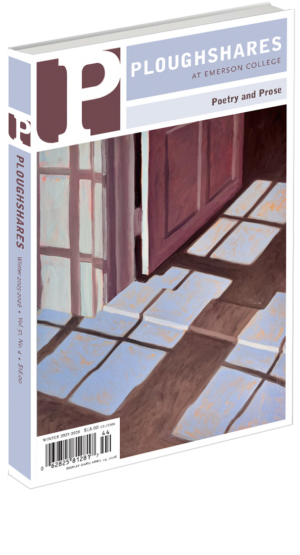

What the Snow Brings

Issue #166

Winter 2025-26

In Sheboygan, toward the end of eighteen months spent stevedoring before disillusionment put him back on the boats, one of the men Tom worked alongside was crushed by a crate when a crane’s strapping gave way and the cargo had...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.