Winter, 1979

Issue #95

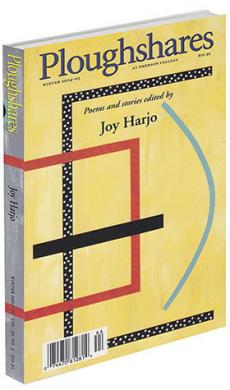

Winter 2004-05

I squeezed the trigger, and another steel beer can wobbled off the fence post with the dull ping of a shiny copper BB. Cocking the gun again, I heard Monkey Tail and Cookie far off. Their sounds came at me...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.