My Ideal Bookshelf* (*For Today)

The package arrived earlier than expected, its corners sharp, its weight hardbound. I tore open the seal and inhaled its out-of-print mustiness. This was the book with all the answers. This book contained all I needed in the world right then.

Giddily, I flipped through photos of crosscut saws and ox-sleds loaded with staggeringly huge logs.

Hooray, hooray for The Wisconsin Logging Book (1839-1939)!

It was just like the day weeks earlier, when my library notified me that my book on Victorian post-mortem photography was in, and I rushed to study the somber sepia-tones of parents cradling dead infants.

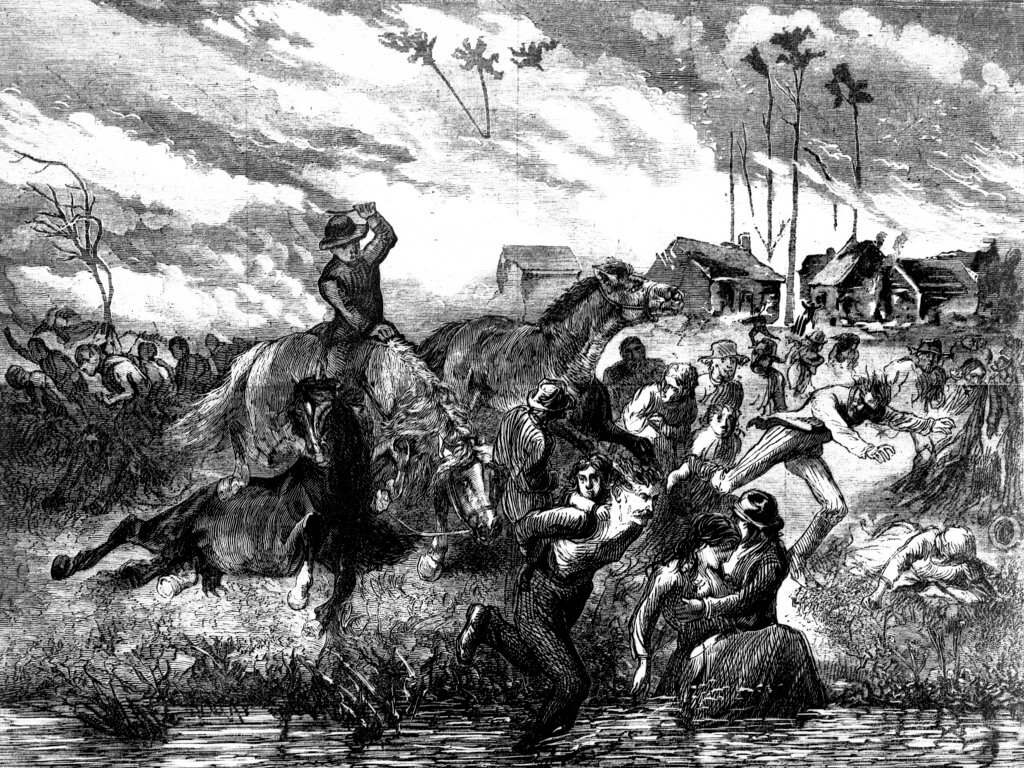

These are not the kind of thrills you can share with just anyone. But they are mine: the thrills of a novelist stacking her ideal bookshelf in preparation to write. For my first novel, I’m researching the means of living, and the arts of dying, in Wisconsin in 1871. This was the year of the Peshtigo Fire, one of the deadliest fires in U.S. history. It’s an event that you’ve probably never heard of. Until I moved to Wisconsin ten years ago, I hadn’t either.

That’s because October 8, 1871, is more famously known as the night of a different fire, the Great Chicago Fire, which killed an estimated 250 people and destroyed millions of dollars of property. The Great Chicago Fire is immortalized in the song I learned in Girl Scouts: Mrs. O’ Leary put a lantern in the shed, and when the cow kicked it over, she winked her eye and said, “There’ll be a hot time in the old town tonight…fire fire fire!”

In reality, fire burned in three states on the night of October 8, 1871. Coincidentally, the buildings that blazed in Chicago were framed with lumber milled in Peshtigo, Wisconsin. And coincidentally, due to a convergence of factors— an unusually dry year in the Midwest, tornadic winds, and the routine practice of clearing land with fire — on the night Chicago burned, so did the town of Peshtigo and multiple settlements in Wisconsin and Michigan. All told, across Wisconsin, between 1200 and 2000 people died.

My ideal bookshelf — an idea I borrow from the wonderful book of the same name by Jane Mount and Thessaly La Force —contains the facts of the Peshtigo Fire: histories culled from survivor accounts, testimonies of meteorologists and Governors’ relief committees, stories of the fire’s peculiar devastations. For each mill worker identified only by a wristwatch in a pile of ash, there were entire families found untouched, as if sleeping, wherever they’d sought shelter — inside hollowed logs, deep in wells, huddled in open fields. Victims also included suicides and homicides. Weeks after the fire, the body of a lumberjack fell from one of the still-standing trees.

Yet there are stories of survival, too. Babies were born on the banks of the Peshtigo River that night. Parents saved children by burying them in the earth. Hundreds of people stayed afloat in rivers, dunking their heads as flames whipped overhead, keeping clear of logs or cows (yes, cows) rafting by.

But however gripping, a bookshelf full of facts doesn’t leave much room for fiction. To find my own space, I’m scrutinizing the narrators of these tales, the details they emphasize or obscure. As Toni Morrison describes in an interview with The Paris Review, it’s a search for “the kind of information you can find between the lines of history. It sort of falls off the page, or it’s a glance and a reference.”

So as I read the Eyewitness Account of the Peshtigo parish priest who survived to write — and sell — his story to raise funds for a new church, I wonder: Whatever happened to the money? In the agonizing letter about a village where nearly every resident died, I linger on the closing lines, where the village founder admits he doesn’t know the names of two entire families. Why not? I’m dazzled by the image of a lumber camp-manager who emerged heroically out of the charred forest at dawn. When he appeared, whose heart leapt in relief?

Who loved that man? Who loved any of them? This is where my ideal bookshelf gets interesting.

Before the fire, and in its aftermath, the characters I imagine had to love, hate, work, loaf, misunderstand, agree, scheme, and hope. To understand them, I’m reading between the lines of books on Wisconsin gardens, lumberjack lingo, Belgian recipes, lumber barons, whorehouses, railroad routes, circus acts, and Menominee Indian folklore. While most accounts of the fire were penned by men, these other books offer glances of the dour village matriarchs, willful teenaged daughters, and wry Menominee wives I can create.

At this point, my ideal bookshelf is more like an ideal bookcase. And this doesn’t include all the shelves of fiction I’m using as guidebooks.

Ten years ago, while writing a story collection about present-day Midwesterners, my ideal bookshelf was different. Nightly, reverently, I’d study the collections of Richard Bausch, Antonya Nelson, Jean Thompson, Lorrie Moore, and Dan Chaon. Reading those books taught me how to create well-intentioned loser characters, how to shift narrative time and space, and how to shock a reader with a gesture that is actually intrinsic and foretold.

Now, as I write a novel centered on an actual disaster in history, I need to learn how to write chapters, connect multiple narrative arcs, and make characters authentic without delivering lectures. My current ideal bookshelf includes novels by E.L. Doctorow and Louise Erdrich, masters at interweaving storylines and placing humor. I seek Andrea Barrett’s guidance for how to make science intriguing and tighten the winch of tension. Hopefully, Emma Donaghue and Edwidge Danticat can show me how to enter the consciousnesses of ordinary people left voiceless in the pages of history. From Don DeLillo, I seek permission to invent the truths that serve my story. On every ideal bookshelf I save a place for Toni Morrison who, as always, reminds me to be brave.

The authors of The Ideal Bookshelf discuss how our inspirations change: “It’s a snapshot of you in a moment of time. You could build an ideal bookshelf every year of your life and it would be completely different. And just as satisfying.”

Today, right now, this is my snapshot. What is yours, and why?