Mooning for Jack London: A Surprise Crush

Jack London was one of the last dead authors I expected to charm me. I associated him with wolves (because of the familiar The Call of the Wild book cover) and, unfortunately, Disney movies (because of the adaptation of his novel, White Fang). Of course, I had never actually read him.

Now, I wish I hadn’t waited so long. I was terribly charmed by The Valley of the Moon, a 1913 gem I found in the farthest, dustiest corner of my favorite used bookstore. Maybe because it was January and I was itching for a trip west. Or maybe because winter leaves the trees so bare and the sky so gray that London’s depictions of the plush Sonoma Valley readily fed my ache for sun.

Or maybe, it was simply London’s storytelling.

The premise of the novel is this: a newly married couple (Billy and Saxon) leave troubled Oakland (where the labor strike is wreaking havoc on lives, including their own) and journeys through central and northern California—on foot!—to find land to farm. The novel’s title comes from an evening conversation where Saxon describes their dream land to friends. I know just the place, her host says, leading her to a telescope on the veranda where “she found herself looking through it at the full moon.”

“I’ve been showing her,” her friend explains when they join the others inside, “ a valley in the moon where she expects to go farming.” Billy and Saxon see the humor, but are undaunted.

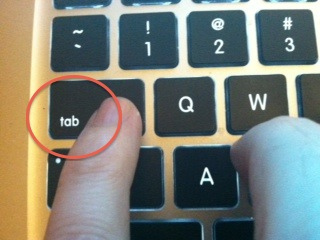

It’s a long, winding journey—530 pages!—so London and I spent quite a few nights curled up together. And it’s a lonely thing, I’ve come to believe, to read a creaky old book with no wobbly underlines, no !!!s, no turned down pages or passionate inscriptions. I’d hoped the book’s previous owners would communicate something to me (if I’m honest, that’s part of what I wanted to see more of in my personal travel through these hundred-year-old books)

But no, with this novel I was journeying alone, which in some ways is incredibly ironic since the novel is hardly an isolated, lonely narrative. It’s been called the “road novel fifty years before Kerouac.” And it’s got all the makings—quirky characters, scenic lands, poetic situations and movement. Though one of London’s lesser known works, the novel is still in print today (the modern-day cover doesn’t even come close to being as cool as the 1913 version.)

Several of London’s personal interests seem to wind through this narrative. And I’ve been fascinated to know the writer more in how he uses those particular interests to flesh out this story.

Here’s a quick list:

Boxing

Billy, the husband, is a much-admired boxer, but by the time he meets Saxon, he’s given it up. He explains why on their first date.

“It ain’t the fightin’, it’s the fight-crowds. Of course, fightin’ hurts a young fellow because it frazzles his silk outta him an’ all that. But it’s the low-lifers in the audience that gets me…. It makes me cheap.”

Billy was referring to an audience who just wanted a blood-bath, not a sport. London felt the same way. He, too, was an amateur boxer and regularly kept up with the sport. He especially loved the science and art of it. Billy’s boxing history pops up throughout the novel, sometimes because he takes on a fight, other times because he’s talking about the art of it.

Valley of the Moon

It’s actually closer than the moon. London had a ranch in Sonoma Valley and believed that the Native American word sonoma meant valley of the moon. He was drunk off the region:

“The grapes on a score of rolling hills are red with autumn flame. Across Sonoma Mountain whips of sea fog are stealing. The afternoon sun smolders in the drowsy sky. I have everything to make me glad I am alive. I am filled with dreams and mysteries. I am all sun and air and sparkle. I am vitalized, organic.”

In many ways, The Valley of the Moon is a love letter to land that he loved. As Billy and Saxon round the bend toward what will be their new home

“they were suddenly enveloped in a mysterious coolness and gloom. All about them arose stately trunks of redwood. The forest floor was a rosy carpet of autumn fronds. Occasional shafts of sunlight, penetrating the deep shade, warmed the somberness of the grove. Alluring paths led off among the trees and into cozy nooks made by circles of red columns growing around the dust of vanished ancestors…”

Experimental farming

Billy and Saxon know absolutely nothing about farming, though they are convinced this will be their new life. Part of their journey involves meeting scores of folks who farm well using unorthodox methods for their time. Saxon, especially, is good at observing and asking questions, a trait she and London apparently shared.

By 1913, London owned more than one thousand acres on Sonoma Mountain. Here, he farmed and raised livestock using methods he gleaned from astute observations, research and his travels. Some of these methods hinted at the organic and biodynamic farming that are more intentionally used today.

I’m still bound by winter on the East Coast, but I’m dreaming of Sonoma Valley. Mental trips are better than nothing, and the internet helps, too. So consider taking your own road trip. Visit Jack London State Historic Park in Glen Ellen, California. I’ll even send you my copy of London’s novel with all the page markings, cracked spine and all.