Chucking “Art for Art’s Sake” – Writers and Social Impact

One morning in late September, I found myself backstage at the “Annual Day of Peace” in Covington, KY—an event that kicks off October as Domestic Violence Awareness Month. I’d been asked to perform a song I wrote about my family’s history of domestic violence, and was listening as speakers urged the young audience to find—and use—their voices to prevent violence. I wondered how many listeners were writers, performers, artists, and how many might go on to use their art as voice, changing their communities in the process.

Leaving that day and re-entering the media binge on the word “shutdown,” I couldn’t help thinking about writers around the globe: how we use our voices; whether (and how) we’re heard. I also couldn’t help thinking of Audre Lorde:

We lose our history so easily, what is not predigested for us by the New York Times, or the Amsterdam News, or Time magazine. Maybe because we do not listen to our poets…

Creative writing has the potential to change perceptions, elevate public discourse, inform, protest, and/or bring awareness to difficult issues and situations. Could we do more with this potential? Should we?

Before anyone gets politi-scared, hark! I don’t believe writers should start “politicizing” all our work, or Woodie-Guthrie-ing our poems for the greater good. But I do believe that if we’re moved by any current economic, cultural, political, and/or social suffering, there’s a place for us—and our craft—in the fray.

But how? Where? If you’re interested in finding your writerly place in this kind of work, here are three steps even non-“activist” writers can take to dive in:

- Identify Our Stories

- Re-imagine “Going Public,” and

- Chuck “Art for Art’s Sake.”

1 (a). My Story.

So, the song I performed at that Day of Peace event: several years ago, I wrote it for my mother, and for my partner’s; both women had been victims of some type of domestic violence. I never planned to release or perform the song. It was too personal, and the topic felt too heavy to bring up during a show. But on a whim one night we threw it onto our set list. Confession: I cried my way through it. And I assumed I’d made an ass out of myself.

Which I probably did. But afterwards, and in the years since, that’s the song everyone wants to talk about. Listeners regularly share their own stories of abuse with us; sometimes it’s the first time they’ve old anyone. People tell us they’re grateful there’s a public “forum” for a topic our culture shutters. They want to buy the song and send it to people they know who’ve been victimized. They invite us to participate in benefits and awareness campaigns. They wonder who they know who might be suffering, and how they can help.

This experience speaks far less to any (accidental) activistic prowess on my part than to the power of sharing stories, and of connecting those stories with overarching issues. It’s taught me that as a writer, I’m most relatable when most vulnerable, and that I can complement my songwriting by being “vocal” in other ways: public speaking, tweeting, blogging. I couldn’t have predicted my listeners’ responses when I wrote “You Did Everything Right,” but they shaped what I believe about art’s role in society. I can’t get rid of the knowledge now that poetry makes things happen.

1(b). Your Story.

“Making thing happen” doesn’t mean writers have to go for overt activism. My song wasn’t attempting to “raise awareness” or protest violence. But now when I perform it, I talk about the situations that inspired it—and the cultural silence surrounding domestic violence. By doing so, the song becomes a catalyst for action and for conversations about silence, victim-blaming, and the ubiquity of violence.

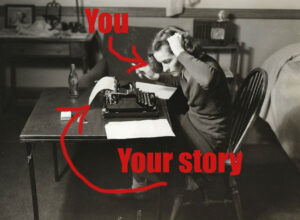

So if writing about an issue feels silly, lame, or daunting, start with your story. Your experience. Let yourself write naturally in response to the social/community issues that make you crazy, hopeful, depressed, or enraged. Social impact may be less about how we approach our writing (“Imma be an activist!”) than about what we do with our work when it’s finished. So: what can you do with the emotions your work incites? with paratextual material? with the thoughts you share via social media?

2. Going Public.

This post-writing work is partly about finding creative ways to go public. Writers can’t control whether we “get published,” but there’s no need to wait for a gatekeeper. How else could your work get out? Where might a specific poem or story be effective?

For example, although I released “You Did Everything Right” on an EP, most of the attention the song received resulted from connecting it with womens’ crisis centers and campaigns regarding social silences and/or violence prevention. These connections aren’t going to get me a book (or record) deal, but they put the song where it’s deeply-heard, and relevant. So think unconventionally: Who are the readers who might immediately resonate with your content? Where are they? What do they read? What sites do they visit? Put your work there.

3. “Art for Art’s Sake Doesn’t Really Exist for Me.” (Audre Lorde)

This public reaching toward social impact only works if we feel confident giving our art this kind of role. For that, Audre Lorde—successful poet, essayist, public speaker, activist, and general defier of categories—provides a great model. Her description of protest—“a genuine means of encouraging someone to feel the inconsistencies, the horror of the lives we are living”—feels approachable for many of us, even if we don’t consider ourselves “protest authors.” It signals a commitment not to politicization, from which we may recoil, but to the power of human emotion to effect change. Lorde’s wielding of this power for the sake of protest seemed natural to her:

“[T]he question of social protest and art is inseparable for me. I can’t say it is an either-or proposition. Art for art’s sake doesn’t really exist for me.”

Following Lorde’s lead, throwing out “art for art’s sake,” at least for a while, may generate creative, risk-taking work. We should of course avoid manipulation, salesmanship, and poems that read like brochures. But that doesn’t mean we have to avoid placing our art in the service of an overarching goal.

Lorde influenced her political and social environment because she sought to do so. We too can write what moves us, and then work energetically, publicly, and proudly to connect it with a wide (and broken) world.

“How do you deal with things you believe, live them not as theory, not even as emotion, but right on the line of action and effect and change?” (Audre Lorde)

Give Us Advice! Links! Comments!

- Got advice for getting started in the realm of advocacy, silence-breaking, social change? Please share!

- Have you seen (your) writing have a positive public/social impact? Where/when? Post a link so we can check it out!

- What activist/protest/advocacy writing are you loving lately? Link to a sampling if you can.

- Other ideas for “supplementing” our writerly work?