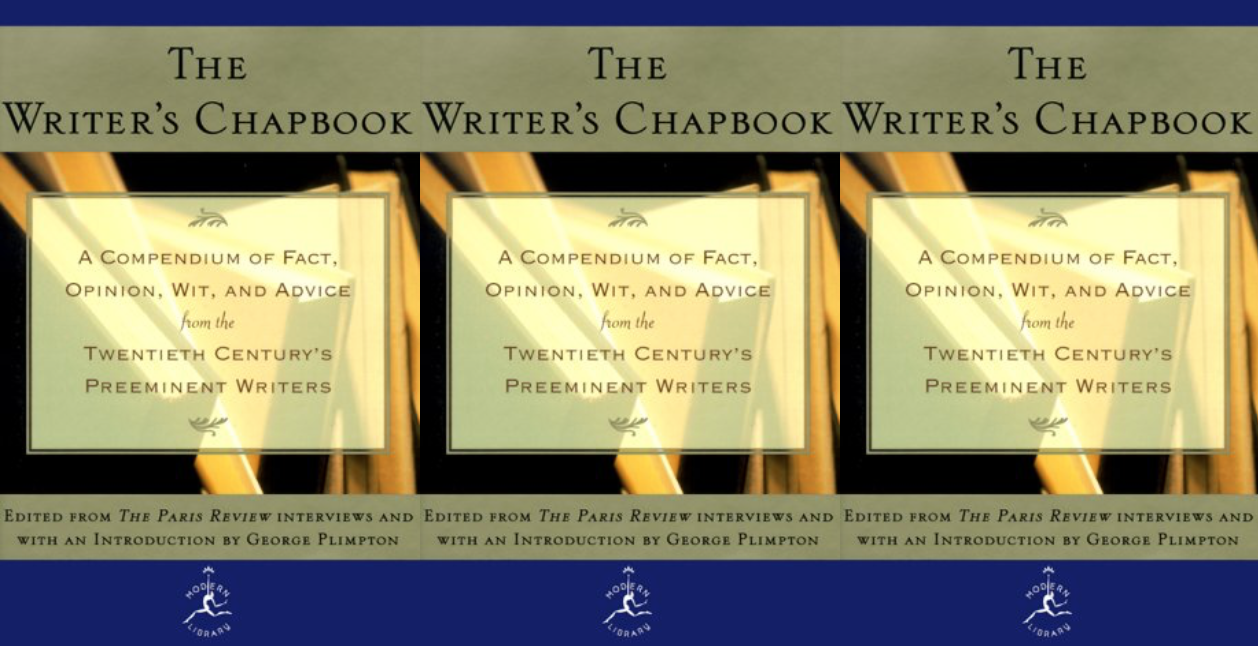

Why I Reread The Writer’s Chapbook

I love The Writer’s Chapbook. Compiled by the late, great George Plimpton from the Paris Review’s Writers at Work series, this volume is a collection of wisdom from 20th Century writers about anything and everything literary, from first efforts to children’s books, from sex to writers’ colonies (which often go hand-in-hand). The section on technique is useful to me as a teacher, since I can pull helpful quotes about dialogue, character, plot, etc. and feel the support of the ages as I deliver some basic information.

I love The Writer’s Chapbook. Compiled by the late, great George Plimpton from the Paris Review’s Writers at Work series, this volume is a collection of wisdom from 20th Century writers about anything and everything literary, from first efforts to children’s books, from sex to writers’ colonies (which often go hand-in-hand). The section on technique is useful to me as a teacher, since I can pull helpful quotes about dialogue, character, plot, etc. and feel the support of the ages as I deliver some basic information.

One of my favorite parts is “On Reading,” where writers list other writers and works they admire. I enjoy, for example, learning that Auden’s favorite childhood collection of poetry was Harry Graham’s Ruthless Rhymes for Heartless Homes, an excerpt of which follows:

Into the drinking well

The plumber built her

Aunt Maria fell;

We must buy a filter

We also discover that Mailer read Forster, that Pasternak read Faulkner, that Marquez, not surprisingly, read Kafka. Other sections detail motivation, work habits, revising, critics, giving readings. In a way, it’s like what going to AWP might have been before writing programs existed—without any of the discomfort that Joseph Heller describes in the section called “On Social Life”:

I don’t think writers are comfortable in each other’s presence…There’s always an acute status consciousness relating to how high or low a writer exists in the opinion of the person he’s talking to.

“On Inspiration,” is a section I often return to for the way it describes the many sources of story: Faulkner began The Sound and the Fury with only a mental picture of Caddy’s muddy underwear; Doctorow began Ragtime by describing the wall of his house in New Rochelle; John Irving begins with the truth, with real people who morph into more interesting characters.

The section on critics reveals the unsurprising information that most writers struggle with reviews, whether it’s Cynthia Ozick, stung because Time added a year to her age, or Irving who insists that what reviewers criticize is often the best thing about the work.

But my favorite section by far is called “On Performance,” which includes, mostly, great laments of writers about writing, and is very comforting to me. Roth says “beginning a book is unpleasant” and Robert Stone says writing is “goddamn hard. Nobody really cares whether you do it or not.” Edmund White reveals that he wishes he were “more at home with writing. I can go a year or two or three without picking up my pen and I’m perfectly content. The minute I have to write I become neurotic and grouchy and ill; I become like a little wet, drenched bird, and I put a blanket over my shoulders and I try to write and I hate myself and I hate what I’m writing.” I have many writer friends who love, love, love what they do, and I always listen to them rhapsodize with a kind of despair—the kind of despair I might feel if, while enjoying a dinner with a group of people at a fancy restaurant, I realize I can’t pay for my share. I sit there like White’s little drenched bird, trying to pretend everything’s okay while disasterous exposure looms. This book, thankfully, reminds me that there’s a whole other silent camp of folks who want to love writing but are, perhaps, more likely addicted to setting up a torturous, unnecessary task so that one can feel relieved after having accomplished it.

This is Angela’s seventeenth post as a Guest Blogger.