Etymology as Pedagogy: How Words Teach Me to Live

When I learned, not long ago, that the word “daisy” comes from the Old English word “day’s eye,” referring to how the petals open at dawn and close at night, I was delighted. Here was proof that the English language can be governed by a beautiful logic. It was a happy reminder, too, that what I thought belonged to me did not. The words I use have been elsewhere, passing from mouth to mouth, me just a mouth in between.

A little later I learned that the word “squirrel” comes from Greek words meaning “shadow-tailed.” More delight. This was evoking in me, I realized, the same adolescent wonderment of discovering that my parents were not parents all their lives, that they were proud participants of the sexual revolution and also shoplifted more than once. What I thought belonged to me did not. It became clear that words are very much like people.

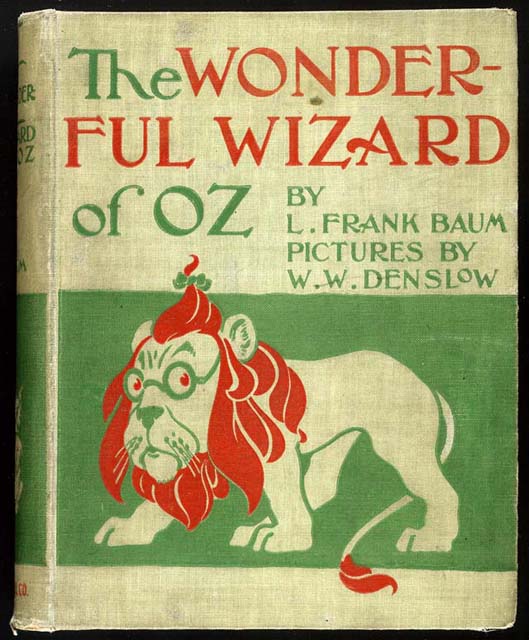

John Ciardi wrote that words are four things: they are a picture (an image), a feeling (a denotation as well as a connotation), a sound (they involve the muscles), and a history. Isn’t this true of people? We sense and feel–and weren’t we given breath by forces beyond our control? I became interested in words being made, leaving, and coming back changed, for better or worse. I made a list of words we know today as joyful that had viscerally dark, violent beginnings long ago: “enthrall” comes from words meaning “enslave”; “rapture” comes from “abduction”; “astonish” comes from “thunderstruck”; and “ravish” comes from “rape” (how can we ever refer to another body as “ravishing” again?).

All nouns, of course, have their origin stories: objects, and ideas, and beliefs are no exception. Here’s one example out of infinity: High heels were elite riding footwear for men about four hundred years ago. (How can we ever refer to pumps as unmanly again?)

Because people don’t come with dictionaries, we must learn each others’ etymologies through other means. Writers often make the best listeners, and enough close listening reveals that we’ve all had some degree of darkness in our beginnings, that we’re all products of upbringings, none of them exempt from turbulence; it’s just that words’ troubled upbringings can be centuries long.

In this way, my love of words has made me more forgiving of people. I can’t help but think of a bully as someone who must have suffered unimaginably himself. Or a strange person as someone who’s lonely, or scared, or just plain weird–and so what? Weird is a good thing. This is not a saintly perspective; this is a literary one. I think most writers believe, quixotically, that both words and people are perpetually in their formative years, that the survival of both depends on change, and that both can be changed for the better.

Reading fiction enlarges our sense of empathy, is the most popular contemporary buzz-sentence, and also one I believe in. But I’m talking here about the units of fiction, the words themselves. My concern with language has made me, if not more empathetic, then at least more aware that trying to be empathetic is both good and possible. If this is living the writer’s life, then I hope it never ends, and that it never stays the same.