Round-Down: On Women Writers And the Fallout from ‘Confession’ in the Digital Age

Social media is in the spotlight—or crosshairs, as it may be–in the literary landscape this week. Several articles and author interviews have touched upon both the benefits and the tremendous costs known to an author maintaining their online presence, none of them coming to a firm conclusion about whether it’s better to be Harper Lee or Hanya Yanagihara, Cheryl Strayed or Elena Ferrante when promoting a book. All of the attention being paid to how we market ourselves online has me asking: Does social media pose yet another disadvantage to women writers? Or is it a blessing that gives us easier access to mainstream audiences? Women are particularly vulnerable to the lure of public confession that the internet seems to demand—and they are most likely to be the ones to suffer fallout from it.

After Laura Bennett’s piece in Slate raised the question of whether publication of personal confessions is exploitative, The Guardian interviewed a variety of editors for outlets that often publish gone-viral first person essays. Curiously, all of these editors were themselves women and not all of them agreed on whether women were more likely to write confessionals than men.

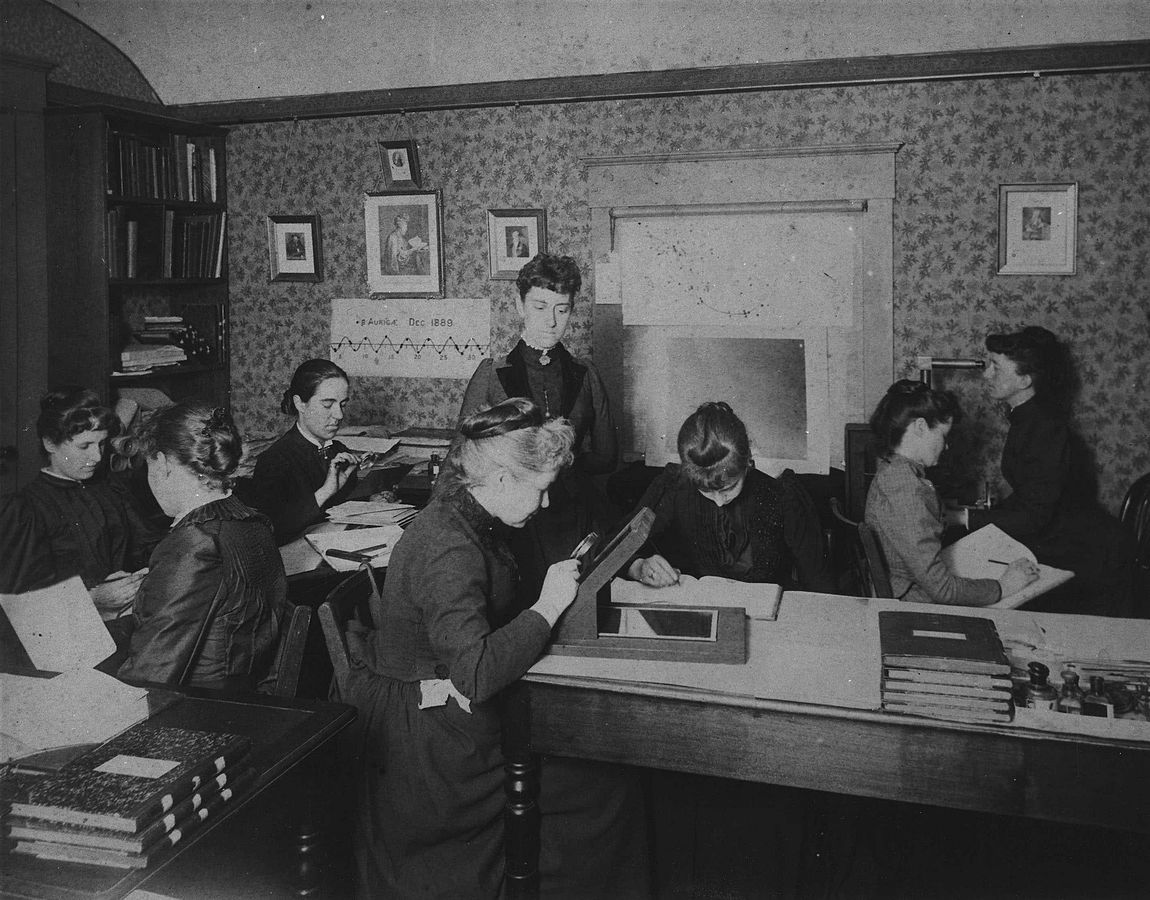

My studies of literary history have revealed that the hyper-awareness of a woman writer’s biography has always, always garnered more attention than a male writer’s—and our obsession with a woman’s biography over her work has in some ways doomed many women writers either to obscurity or to the assumption that more women write more personally than men. For example, no one today doesn’t know the name of William Shakespeare. And yet, who among us recalls Mary Darby Robinson, an eighteenth century sonneteer? While she was alive, her personal life was of great interest to many critiquing her work. As Paula Backscheider puts it in her book, Eighteenth Century Women Poets and Their Poetry, “That [Robinson] succeeded Robert Southey as poetry editor of the Morning Post and died arranging a three-volume collection of her poetry is seldom mentioned, but the ‘autobiographical’ aspects of [her poetic sequence] Sappho and Phaon (1796), with its ‘jilted’ woman’s voice, nearly always attracts comment.”

The apparent need for critics to comment almost exclusively on a woman writer’s autobiography is a frustrating trend that has continued to this day. Another example: while at the Associated Writers and Publishers conference in Minneapolis this past April, I attended a panel where poet Jan Beatty heatedly warned the audience that “confessional” was a derisive term used by men in the academy to dismiss female poetry. Hers was an ironic point given that the confessional movement started with Robert Lowell but is best remembered by many via the works of (and harrowing personal details about) Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton.

In the Slate piece, Bennett quotes Jia Tolentino, the features editor at Jezebel, who states this obsession with personal first-person confessionals has created “a situation in which writers feel like the best thing they have to offer is the worst thing that ever happened to them”—and I would argue, as many have done in the last few days, that this is particularly true of women writers.

Bennett asserts that the reason this is more acutely a problem for women writers, “—aside from the fact that the ‘confessional’ essay as a form has historically attracted more women than men—is that so many of the outlets that are most hungry for quick freelancer copy, and have the lowest barriers to entry for publication, are still women’s interest sites.”

Like Doree Shafrir, ideas editor at BuzzFeed, I’m not sure I entirely agree with Bennett. While Bennett’s is a point that is a good starting point, I’m wondering how much of our cultural memory is doomed by habit to pay more attention to a woman’s autobiography and any of her so-called confessional writings, and to inflate their place in a woman writers’ oeurve, even as we at the same time condemn a woman for such publicly self-indulgent frivolity.

And yet, it’s not all gloomy for those of us who feel trapped by our cultural need to link to blogs, Twitter feeds, and Instagram accounts. In an interview for Publisher’s Weekly, poet Mira Gonzalez mused on the benefits of the internet boom for writers. In her mind, the “availability of the internet as a tool for self-promotion to all types of artists no matter their background has created a level playing field of sorts. It’s no longer about wealth or access to a publicist, now it’s more about the artist’s ability to market themselves.” But even she comments on the discomfort inherent in exposing herself online, saying, “I wouldn’t necessarily say it feels comfortable to me.”

Furthermore, editor LaToya Peterson has an important point for all of us needing to consider how complicated this problem is. “This overshare, gross-out phenomenon of ‘first-person writing’ is generally a door that leads to more fame and work for white women. It is selling pieces of yourself to get bylines. This route to publication and a book/movie deal simply is not open for non-white women. Society sees women of color’s shameless writing as proof of deviance, not a relatable and fun story to share on social media.” One only has to look at the varied responses to a literary phenomenon, The Help, to realize the veracity of her statement. In the novel, a white writer writes about a white woman writer in the South who records the stories black maids are unable, for fear of their lives and of the fallout guaranteed from telling the truth about them, to tell themselves. The book was a success and went on to become a movie, all while stirring some griping and grumbling about the political ramifications of the book’s entire set-up.

Peterson goes on to assert that, “For some reason, the lives of men are [considered] inherently more serious affairs than the lives of women.” Editor Emily McCombs agrees with Peterson on the last point, stating, “The whole language of ‘oversharing,’ ‘TMI,’ and ‘confessional blogging’ is condescending and dismissive. Nobody uses that kind of language when men write memoir.” I myself can attest that in my MFA program, there are many women writers who feel discouraged and demeaned by similar branding–on and off line–of their work as “sentimental” or “chick lit,” when in fact they are working just as hard as their male counterparts to craft a narrative persona, to spin secrets, personal or otherwise, into works of art.

So is the only way as a woman to escape this sexist spin of our art to eschew social media outright? Alexander Chee has a wonderful piece up at LitHub about Italian author Elena Ferrante, which seems to suggest that Ferrante’s anonymity is “something of a feminist project, also.” He expands on the notion: “No one is able to talk about her appearance. No one can decide if she is a good or bad mother. No one can decide if her work is the product of this or that biographical event—and evaluate it by that single event, and its perceived fidelity to that event. One can talk about her work, really, or her relative anonymity (the constraints of which force you back to the work).” Imagine that! Chee points out why this is a novelty: “No one wants to do this for women writers usually.” Or really any woman brave enough to stand in the spotlight (looking at you, Carly Fiorina and Hillary Clinton).

The way I see it, we as women writers have three options if we want to engage with the matter of author self-promotion in socially responsible ways. We can either opt out of virtual reality entirely, like Ferrante, and write ourselves as work-that-stands-alone, without the author, so that our private truths and traumas retain their own private power. Or, as Gonzalez does (all while being cognizant of the ways in which our racial identity is a factor as much as our gender in this matter, as in all matters), we can acknowledge the limited ways sharing with an online community can both help and harm our careers. Finally, as all readers and writers, we can demand more self-awareness before we “share” or “post”—or even before we label and categorize each other, especially other women–all in our efforts to be heard and taken seriously. This last option is probably harder and would ask that all of us engage in the kind of harsh self-criticism that is the only way forward to change.