Innovators in Lit #6: Melissa Broder

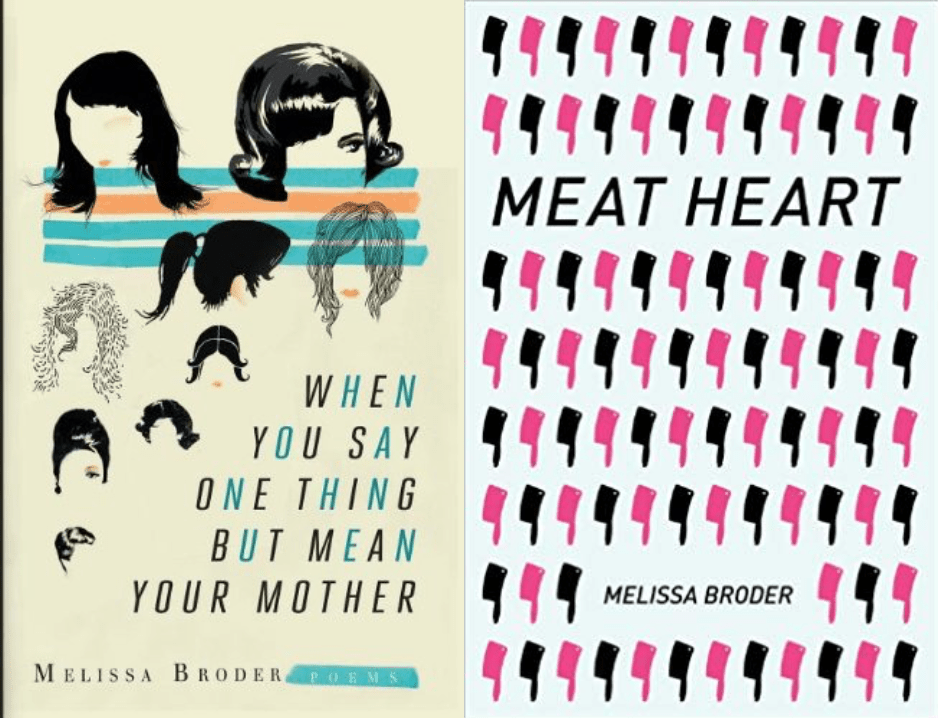

Melissa Broder is the author of two poetry collections, Meat Heart (Publishing Genius, 2012) and When You Say One Thing But Mean Your Mother (Ampersand Books, 2010). She edits La Petite Zine and curates the Polestar Poetry Series. By day, she is a publicity manager at Penguin. I was excited to speak with Melissa because, in addition to being an accomplished poet, she is connected to both the “major house” world and the indie landscape—and thus offers an interesting perspective for this series. Below we have talk of making colors into nouns, alchemy, what sells poetry, an indie lit boy pin-up calendar, and the part of the publishing process when “you’re left with you again.” Yes, all that. So read on.

Laura: You’re the Chief Editor of La Petite Zine. I loved your current all-women issue. How did that come about?

Melissa Broder: Certain journals are comprised of mostly male writers, but they’re never called “the men’s issue.” So we thought: what if we publish an all-female issue but we don’t address it as such. We won’t call it a women’s issue; we’ll just call it an issue. This turned into an experiment to see how long it would take for readers to notice.

We actually considered publishing two men in the issue to create an alternate universe-version of what a lot of journals look like. At one point it was 16 women plus Jason Bredle and Noah Falck. But we decided to keep it all women, and Bredle and Falck will be published in our next issue in October.

Laura: How long did it take readers to notice?

MB: Hmmm. Hard to say. Some people noticed right away, and some never noticed at all!

Laura: LPZ has been around since 1999, a fairly long time in lit mag land—what’s the secret to LPZ’s longevity? Kale? Fish oil capsules?

MB: There’s always been something special about LPZ. I’ve had a crush on her for years. I think it’s that we’re very selective in curating the text, but we’re not stodgy. The editors before us, Danielle Pafunda, Jeffrey Salane, and Daniel Nester had discriminating taste coupled with a sense of levity. We’re trying to carry on that tradition.

Laura: Your second book of poems, Meat Heart, is forthcoming from Publishing Genius in 2012. Tell us more?

MB: It’s exciting to be published by PGP, because I love their books. Rachel B. Glaser’s Pee On Water is a total trip; it’s like the bulls eye in the center of a cosmic bagel. We Are All Good If They Try Hard Enough by Mike Young takes that navel gaze we poets tend to hold too long and flips it outward. He’s a very generous poet. Mairead Byrne changed the way I think about poetry—I didn’t even know what pattern poetry was before I read her work. She’s a magician. She makes colors into nouns. So I’m in really good company.

Laura: I adore your poem “Waterfall,” which will be in Meat Heart. “& I keep going to god too clean as though god/is frightened of muddy feet” is so killer. Where did this poem come from?

MB: Thank you. I’ve always been fascinated with vomiting. It’s such a primal, involuntary act—sexual even, like ejaculation. It’s disgusting, but it’s real. And I’ve always struggled with the illusion that the spiritual path is a well-groomed, perfect trajectory. So this poem wants to believe that if humans can embrace each other at their most vile, perhaps god doesn’t judge either. Come as you are. Go to god messy. Vomit as holy.

Laura: Sometimes, to my feeble fiction writer ear, poetry can seem either too flip or too self-consciously full of Meaning. Something I love about your work is the tone, that wonderful swirl of casualness and surrealness and profundity. Is a particular tone something you actively cultivate, or does it come onto the page pretty naturally?

MB: It’s alchemy. It’s me, and it’s not me. I write using a word bank comprised of nouns thefted from other texts. I use the stolen language, plus textual constraints like syllabics, so that the dominant and defensive parts of me are no longer allowed to dominate and defend—at least rhythmically and in terms of language. I’m forced to tell stories in new terms, and that evolves the stories. At my best, I’m a channel.

Laura: What do you find yourself frequently editing out of your early drafts?

MB: Lines where meaning totally eclipses language. Lines where language totally eclipses meaning. Anything too tidy, in denotation or in sound.

Laura: By day you’re a publicity manager at Penguin. What exactly does a publicity manager do?

MB: A publicity manager does what a literary publicist does, which is to try and get the media to pay attention to books and authors, and in turn, create a cultural conversation around a text. The manager part means the person has been doing it for a while and probably loves what she does.

Laura: Will your background in publicity inform how you promote Meat Heart? What advice can you pass on to the rest of us?

MB: I learned something while promoting my last book, which is that the media outlets that sell fiction and non-fiction are not what sell poetry. Poetry sells poetry. Poets sell poetry.

I also discovered, firsthand, what is probably my best piece of publicity advice, which is that satisfaction is an inside job. No amount of happy reviews will ever be enough. Every media cycle inevitably ends. Then you’re left with you again—you and the art.

Laura: I’ve been asking other interviewees about this Observer article and its take on author readings. You run the Polestar Poetry Series. What do you hope that readers will deliver at your series? How can authors make events more engaging?

MB: Does everyone dread a reading on some level? I’ll admit I do. It might just be the sitting still and paying attention for a defined period of time-part. So I’ve tried to shake that out of Polestar a bit by holding it in this dark, grungy basement at Cakeshop, a rock venue. My favorite Polestar readings are album nights where poets are each asked to write a poem loosely inspired by a particular song on an album. We’ve done Nevermind, Superfly, Doolittle, and Kid A. In October we’re doing Siamese Dream.

Laura: For this project I thought it would be interesting to hear from people who are connected to both the “major house” world and the indie landscape, as you are. In an interview with Publisher’s Weekly, you described your literary life as “two separate but related worlds.” Can you talk a bit more about that?

MB: As far as the “indie landscape” goes, it’s a thrill to see writers who are beloved in the indie world getting picked up by major houses. Recently I can think of Blake Butler, Michael Kimball, Emma Straub, Amelia Gray. But these are prose writers. The poetry world seems to be its own entity, and I embrace that. I’ve always enjoyed the role of the “other,” and I hate competition. So it’s freeing that I don’t have to compete for an agent or feel resentful when a friend gets an agent because I’m a poet, and 99.9% of us just don’t have agents. I love that I don’t have to think about mass appeal; I only have to edit my work to make it strong in itself. Sometimes I’ll be in a sales meeting at work, and I’ll giggle imagining a poetry book selling in its lifetime what a fiction bestseller sells in a week. The New York Times poetry bestseller list. It’s kind of a sweet thought.

Laura: You’re getting a “slow, scenic” MFA at CCNY. What made you decide to do a MFA at this point in your career, with two books under your belt?

MB: When I say slow, I mean really slow. I started the MFA before I ever thought I’d have a book published, and I hope to complete the degree before 2020. I take one class a semester. I do it because it keeps me writing no matter what. And I do it as an MFA because if I’m going to take workshops, why not get a degree out of it?

Laura: What are some other publishers or literary entities that you find inspiring?

MB: Small Press Distribution, Publishing Genius, Wave, Octopus, HTMLGIANT, the poetry section at St. Mark’s Bookshop.

Laura: What do you wish existed in publishing that hasn’t been invented yet?

MB: An indie lit boy pin-up calendar.