The Queen of the Night and Alejo Carpentier’s French Accent

In the first chapter of Alexander Chee’s long-awaited new novel The Queen of the Night, the opera-singer protagonist surprises party-goers at a Paris ball by bursting into an aria from Gounod’s Faust. The scene has a scandalous, erotic backstory (too complicated to recount here, but it involves two brothers with a saber fetish) explaining why she sings in defiance and “as a gift to the audience, to the composer,” and to herself. But I want to focus on Chee’s description of the scene, or rather on one paragraph of Chee’s description, in which the singer, nicknamed La Générale, finishes her song:

In the first chapter of Alexander Chee’s long-awaited new novel The Queen of the Night, the opera-singer protagonist surprises party-goers at a Paris ball by bursting into an aria from Gounod’s Faust. The scene has a scandalous, erotic backstory (too complicated to recount here, but it involves two brothers with a saber fetish) explaining why she sings in defiance and “as a gift to the audience, to the composer,” and to herself. But I want to focus on Chee’s description of the scene, or rather on one paragraph of Chee’s description, in which the singer, nicknamed La Générale, finishes her song:

La Générale! The crowd shouted as I finished and came down the stairs, and I lifted my hands into the air to the crowd, smiling. I could feel the applause beat against my skin as it echoed and grew. A woman screamed as her dress swept the candles on her table and caught fire as she stood on her chair to see me. She was rushed to the fountain, where it was put out, and even this was cheered. The group of officers who had roofed my entrance with their swords then knelt, offering them to me, and the crowd changed from shouting my name to laughter as I took one and mock-knighted them all. La Générale! La Générale!

That spectacular detail, the woman’s dress catching fire, is both unforgettable and instantly forgotten, replaced by more sensational images: La Générale breathing fire onto the face of an ex-lover she has just killed, bodies “exploding into storms of blood and bone” during the fighting in Paris after the fall of France’s Second Empire. This is how the novel proceeds: Chee stitches hyper vivid images into intense scenes, which in turn coalesce into a complicated, hallucinatory narrative, in the course of which an unnamed American farm girl becomes a circus performer, a courtesan, a servant to the Empress Eugénie, and a renowned soprano. Though reviewers have praised Chee’s creativity, this aspect seems to perplex critics. “What are we to make of this?” asks Joan Acocella. “It’s a comedy, right?”

As off-putting as Chee’s technique is to some, it felt familiar to me. Let me explain: The backbone of my graduate studies was the work of the Cuban author Alejo Carpentier. I spent the summer of 2012 in Havana digging through his notes and books at the Fundación Alejo Carpentier, at a table in what was once his dining room; I devoted one chapter of my dissertation to his novels, and the rest to an exploration of what his literary theories could tell us about North American writers like James Weldon Johnson and Ralph Ellison. When Chee writes scenes like the one above, I think of the image in “Oficio de tinieblas” of a rosebush growing overnight in the park where cholera patients are quarantined, crowding the dying onto one another. When Chee dedicates dozens of lines to the furs that were found in Empress’s rooms when she fled for London, I think of the absurd inventory of silver items that Carpentier catalogs in the first pages of Concierto barroco.

I could go on and on about the similarities. Both writers build their work around music and theater, for example, and both writers show a love for history in their meticulously researched plots. But, for me, the real parallel between Carpentier and Chee is in the two writers’ shared aesthetic, what Spencer Lenfield calls the “intensified words” that “take on the colors, events, and characters of an enormous opera.” I’m not alone in this judgment. Last month, Chee tweeted: “A Cuban playwright friend is explaining to me how my most recent novel seems more like Latin American baroque to him. À la Alejo Carpentier.”

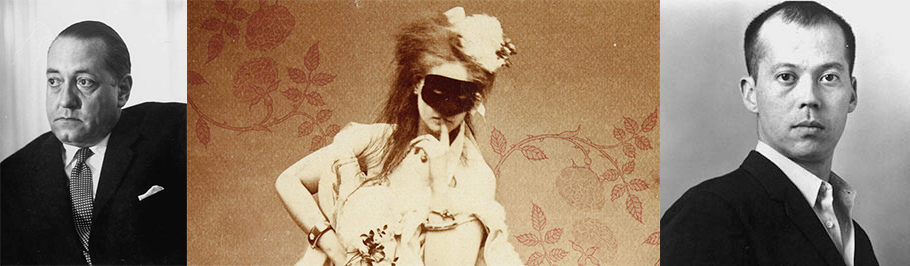

I meant for this post to kick off my bimonthly series on Cuban literature, so it might seem odd that I’m leading with Chee, a Korean-American author who was raised in South Korea, Hawaii, Truk, Guam, and Maine. But Chee’s playwright friend is onto something, and I think the baroque that he sees in Chee’s writing points to something essential, but paradoxical, about Carpentier: namely, his un-Cuban-ness.

Carpentier is among the most canonical of Cuban writers. His career stretched from the 1920s until his death in 1980; it flowered in the 1940s and 1950s, a moment when Latin American writers were deeply concerned with nationalism, trying to distill the essence of Latin America and its various national literatures into writing. Carpentier contributed to this movement, writing at one point that a writer’s true national identity must come from “using one’s most spontaneous language, listening to that which sings in the most intimate elements of one’s being.”

The irony is that Carpentier’s own claim to cubanidad was relatively tenuous. Other authors snickered at his Spanish, which he spoke with a French accent. He always insisted he was born in Cuba, but we now know he was born in Switzerland, to a French father and a Russian mother. He went to school in France, and lived for most of his adult life outside of Cuba. In 1927, to escape persecution from the Machado dictatorship, Carpentier borrowed the passport of a Frenchman, Robert Designs. He passed, easily.

Maybe to compensate for his foreignness, Carpentier insisted that Cuban identity, and Latin American identity more generally, depended on cultural collisions. Much of Latin American culture, he said, was produced from the outside. This accounted for its theatricality, for its exuberance, for its seeming lack of interiority. The extravagance of Latin American baroque art became, for Carpentier, a refuge for the placeless.

“Sometimes you don’t know who you are until you put on a mask,” Chee wrote in “Girl,” his essay about dressing in drag. It’s a notion that Carpentier found at the heart Latin American expression. Chee, I think, would agree. In a follow-up tweet to me, he wrote, “Mexico was the first country I ever felt at home in—a place that could acknowledge me as mixed and whole at the same time.” That’s a good distillation of Carpentier’s descriptions of the Latin American baroque, and it explains how Chee’s serves as a worthy introduction to the works of the Cuban author.