My Uncle’s Books

A year and a half ago, my uncle Chuck died unexpectedly. My family wanted me to have his books because I was a reader like he had been, and I was also a writer. And I wanted the books, especially his Library of America books, which looked so lovely and uniform and canonical. More importantly, I wanted to continue the conversation we’d been having since I’d learned to read—the “what are you reading,” conversation—because we were both always reading something. We were insatiable. We understood this about each other. There were so many things I would miss about him, but I knew I would miss this conversation the most.

A year and a half ago, my uncle Chuck died unexpectedly. My family wanted me to have his books because I was a reader like he had been, and I was also a writer. And I wanted the books, especially his Library of America books, which looked so lovely and uniform and canonical. More importantly, I wanted to continue the conversation we’d been having since I’d learned to read—the “what are you reading,” conversation—because we were both always reading something. We were insatiable. We understood this about each other. There were so many things I would miss about him, but I knew I would miss this conversation the most.

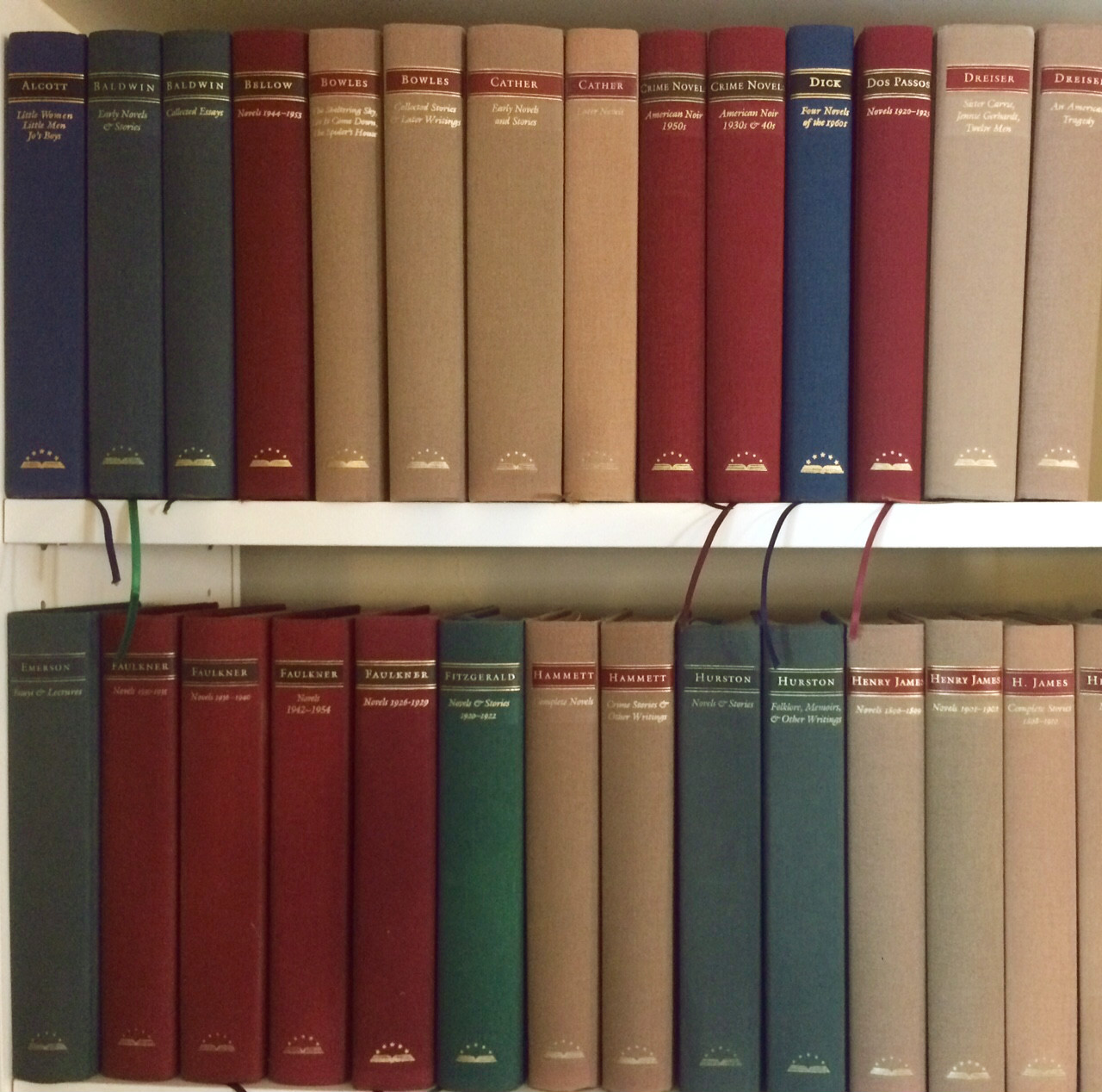

There were about two hundred Library of America books, and my family wanted me to take them all. My home is small. The bookshelves are in my small living room. My inheritance of books was a mixture of boon and responsibility and onslaught. I found a spot for another bookshelf behind the couch. I went through the Library of America books and chose the ones I thought I was most likely to read, all fiction. I stored the other half (George Washington’s diaries and the like) in my mom’s attic. She rarely offers attic space, but she knew I couldn’t stand the alternative just then.

I considered integrating Chuck’s books into my own fiction collection. But it felt strange to disrupt their uniformity, and it felt dishonest anyway. I hadn’t read most of them. It was disheartening to see the sheer quantity of books I hadn’t read—books by Bowles, Cather, Nabokov, Dreiser, Faulkner, Melville.

These volumes were beautiful, so obviously if I had duplicates I should get rid of my paperbacks. But when it came down to it, I couldn’t say goodbye to my battered copy of Another Country, which I had lent out to so many people, whispering, “It’s actually kind of awesomely smutty,” and which had improbably made its way back to me so many times. As I compared the two copies, I remembered that Chuck and I had talked about James Baldwin. His writing had meant something to both of us.

There was further comfort in the overlap. My girlhood friend Louisa May Alcott, whose books I somehow didn’t already have on my shelf. And William Maxwell, Carson McCullers, Philip Roth, and Edith Wharton. I love them all, but then I found myself trying to remember if Chuck and I had talked about them. Maxwell, definitely yes, but what about Wharton? I didn’t think so. What a missed opportunity. Lily Bart! I was sure we’d never talked about her. Or had we? I was brought up short, again, by the terrible thing about death. You can’t ask the dead person anything anymore.

Once I had placed all the books on their own four shelves, I considered the best way to deal with them. I’d just added at least a hundred novels to my to-be-read pile, novels I should have already read at some point anyway, and most of them were a bit, well, heavy.

Chuck had acquired these books from The Library of America’s subscription service over the course of many years. He received one each month, and he had a month to decide if he wanted to keep it. If a book failed to hold his interest, he sent it back. How sane! I don’t think he read every page of every volume that now stood on my shelves, but I don’t think he kept anything he didn’t like, that didn’t teach him something, in its way. I tried to read a few, but like Chuck, I was honest with myself when my interest flagged. I didn’t have the option of sending them back, so I returned them to the shelf.

I hadn’t only been protecting the integrity of Chuck’s collection when I isolated it behind the couch. I’d been protecting the integrity of my collection, which I had created. I’d chosen the books. I’d culled brutally at times, admitting my mistakes. I liked the colorful, rag tag appearance of the spines of my books, arranged alphabetically on the shelves. I liked that I had something to say about each one, even if it was only that I sincerely hoped to read it someday.

So maybe the better place to look for Chuck was in the books he’d given me as gifts, the books that were part of my collection because he’d known I would love them. A beautiful edition of Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass he’d given me when I was a child. The three-volume, clothbound set of Emily Dickinson he’d given me as a college graduation gift. “They put all her dashes back in,” he told me gleefully. A treasure trove of poems about death, but how about this, from 591?

I willed my Keepsakes – Signed away

What portion of me be

Assignable – and then it was

There interposed a Fly –With Blue – uncertain – stumbling Buzz –

Between the light – and me –

And then the Windows failed – and then

I could not see to see –

Chuck died a few weeks after Christmas, and we found the pile of books he had clearly received as Christmas gifts. They all looked crisp and unread. I’d given him a Lorrie Moore collection, Bark. After he’d unwrapped it, I asked if he knew her work, figuring he must, but he didn’t. I was sure he’d like her sensibility, which, now that I think about it, has something in common with Emily Dickinson’s.

“It’s pretty death-obsessed,” I told him, more recommendation than warning. “A little twisted and sad. But so funny.”

“Perfect,” he said, laughing.

We were both a little death-obsessed and twisted and sometimes sad, but we found the same things funny. I think he would have liked Bark. I took it with me. I’d checked it out of the library and didn’t have my own copy. I slid it onto the shelf, where it immediately looked at home in my collection.