In Defense of Lingering: Ethan Canin’s “Pitch Memory”

As a teacher, I am occasionally accused of lingering. One poem by Emily Dickinson can fill an entire class. An hour isn’t too long to unpack the final page of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. I once asked my students to write an essay that examined a single metaphor in James Baldwin’s “Notes of a Native Son.” To zoom in this way—to look carefully at an author’s language, to study the pacing of a paragraph or the shape of a chapter—is the best training I’ve had as a writer. The second best training I’ve had is trying to teach this strategy to students who aren’t necessarily interested in becoming fiction writers themselves, who sometimes like to remind me an em-dash need not be loaded with meaning; sometimes it’s probably just there to perform its grammatical function of extending a sentence. Fair enough. But what’s the effect, dear students, of extending the sentence in this way, in this particular moment?

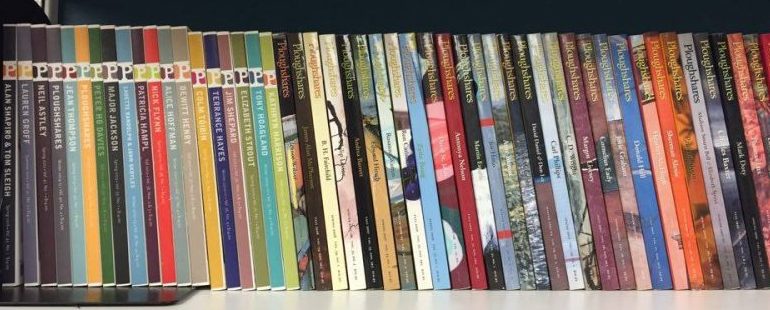

Which brings me to the purpose of this series—From the Archives—where each month I’ll pull a story from the deep well of the Ploughshares archive to see what it has to teach us about writing fiction. We’ll begin in 1984 with Ethan Canin’s “Pitch Memory,” the author’s first and only story to be published in Ploughshares.

A few years ago, when I arrived at a friend’s house for a summer hike, she pushed this story into my hands, and told me that I needed to read it. Immediately. The photocopied story was a little blurry; a few letters occasionally cut off from the right side of the page. It was clearly a hasty xeroxing job. She went inside her house to do something—what, I don’t know—and I sat on her front steps and read the first two lines:

The day after Thanksgiving my mother was arrested outside the doors of J.C. Penney’s, Los Angeles, and when I went to get her I considered leaving her at the security desk. I thought jail might be good for her.

A klepto-mom, a holiday arrest, a resentful daughter? Canin had me. I was in, ready to see how this mess unfolded, anticipating the mother’s shame of having been caught, the narrator’s smug satisfaction in having rescued her mother. But Canin had other ideas. He suspended me there, left me wondering about the Black Friday arrest, and leaped back to three days before, the day the narrator arrives at her childhood home for the holiday visit. My first thought: can he do that? (Answer: yes, of course.) My second thought: why does he do that? What does it accomplish for the story?

A writer once told me that the key to writing fiction was to make a reader want something and then make them wait for it. That seemed a little cruel, I thought, but as soon as he said it, I thought back to all those stories that kept me up well past my bedtime, all because the author was dishing out what I wanted in the smallest satisfactory bits possible. Manipulation, with its decidedly negative connotation, seems like the wrong word here. After all, isn’t it our job as writers to keep our readers from setting our piece down and not returning? In an interview with The Paris Review, Amy Hempel puts it like this: “Some writers feel that when they write, there are people out there who just can’t wait to hear everything they have to say. But I go in with the opposite attitude, the expectation that they’re just dying to get away from me.” From this perspective, Canin’s enticing opening and his leap away from the arrest doesn’t seem cruel at all. It seems smart. It seems like he knows I could put the story down, go find my friend, and leave for that hike.

So here’s the thing. I thought I cared about the mother’s arrest, I really did. It’s what pulled me into the story, the thing that kept me reading, but by the end I realized this wasn’t what I cared about at all, because while I was focused on the arrest, looking for an answer to how it happened, how the daughter got her mother out of this tangle, whether the mother apologized or thanked her daughter or offered something in between, Canin was hitting me with passages like this:

Her stealing started after my father died, though he had bought three-times his worth in life insurance and had already made the last house payment by the time his coronary artery closed up on Friday evening after work. That day was the meridian of my mother’s life.

What materializes is a portrait of a family in grief, still, eleven years after the death of the narrator’s father. It’s the story of this unnamed narrator trying to find her place in the family. It’s a story of two sisters, one who becomes a cardiovascular surgeon in response to her father’s fatal heart attack, the other who flounders a bit in her professional life but emerges as more observant and in tune with her mother’s needs. In this way, we might see the leap back of the first two lines as more than a tease but also as a distraction. While we’re focused on the arrest, Canin slips in grief. He gives us something bigger to care about.

If the arrest doesn’t offer the emotional punch of the story, it does offer a necessary frame. It’s the event that justifies the telling of it. Without the arrest, there’s no reason to talk about the grief, no reason to show these three women singing together, no reason to depict a terribly uncomfortable Thanksgiving dinner or its aftermath. The arrest is the answer to those crucial questions for fiction writers—why this story? why now? For anyone who has ever heard it’s not clear why your narrator is telling the story, Canin’s “Pitch Memory” is worth reading, a good one to linger on.

“Pitch Memory” was originally published in Ploughshares in 1984 and was republished four years later in Canin’s debut collection Emperor of the Air.