Out With the Old and in With the Ancient: The Bible as Literature in Translation

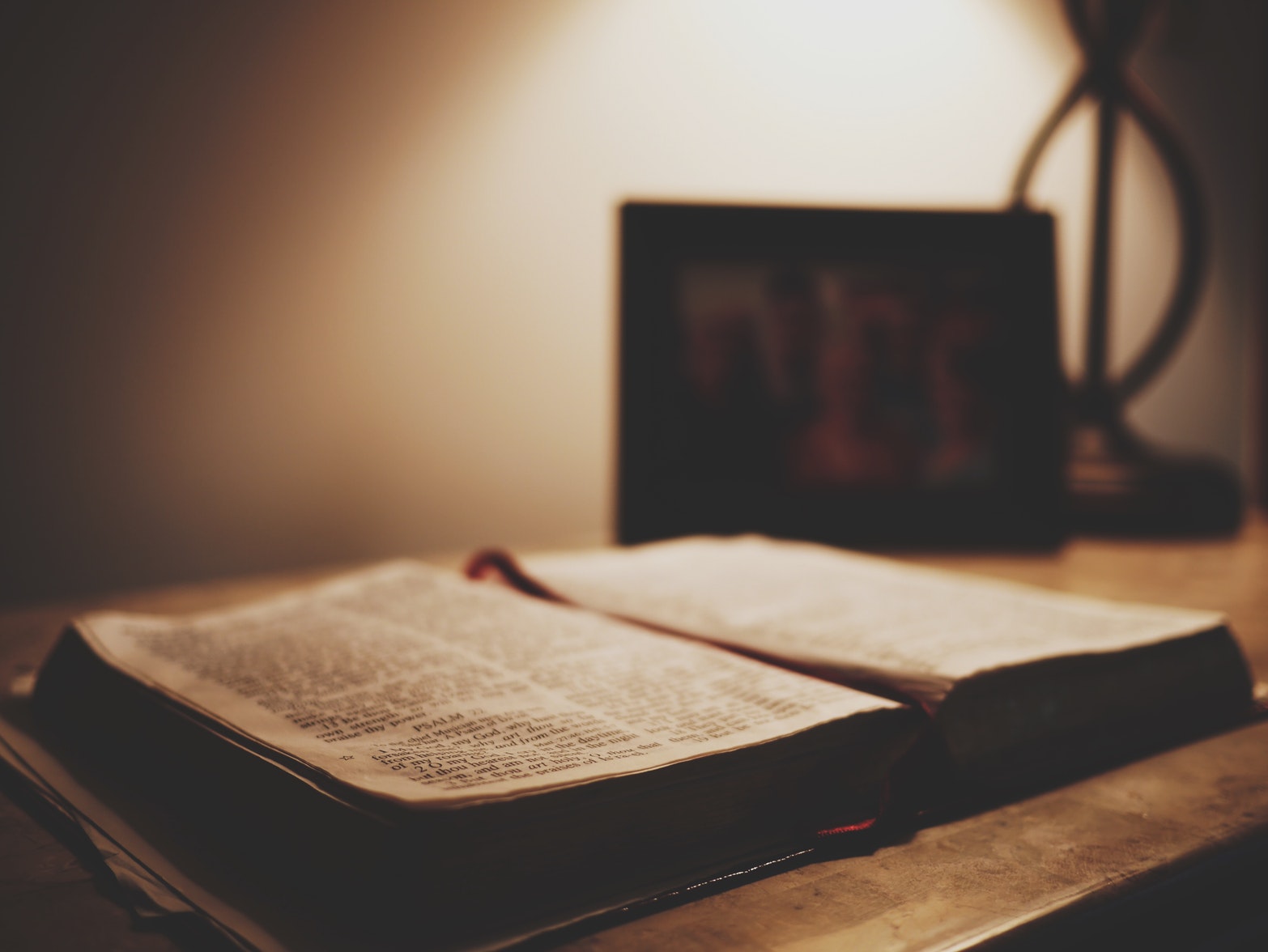

It isn’t only Israeli politics and government agenda that hang on the narratives of the Bible—the Hebrew language is profoundly steeped in biblical passages, references, and turns of phrase. When one goes to investigate the origins of a saying, idiom, or bit of slang, more often than not the source can be found in one of the stories of the Bible. Biblical allusions are not unique to the Hebrew language, but in no other language can they be found with such prevalence. To us Israelis and Hebrew speakers, the Bible is both myth and lore, God’s word and Shakespeare.

When translating Hebrew literature, these allusions would usually be transformed into an equivalent English phrase or slang, whether biblical itself or not. While ‘hoseh shivto sone bno’ would be translated into ‘spares the rod, hates his son’—an accurate translation of the same biblical quote, equal in meaning and awfulness—a phrase like ‘b’rachel bitha haktana’, which originates from the story of Jacob and Rachel and translates literally as ‘in exchange for Rachel, your youngest daughter’ (used in Hebrew as a metaphor for being painstakingly clear about one’s intentions), would probably be translated in the context of a non-biblical story as ‘explicitly’ or ‘no two ways about it’—leaving the matriarch entirely out of it.

Our fascination with the Bible isn’t merely lingual. We simply can’t seem to get that book out of our heads. Israeli literature borrows plotlines, characters, and structures from the Bible, and often it can’t help but create reimaginings or sequels to it. This August will see the publication of a book I spent a large part of last year translating—The Secret Book of Kings, by Yochi Brandes, which will be published by St. Martin’s Press. In it, Brandes retells the stories of Kings Saul and David and of the rise and fall of the lineage of David, spinning a subversive yarn, at once both firmly founded in fact and wild with creative fiction. Naturally, the novel contains countless biblical quotes, which had to be translated as well.

Unlike biblical turns of phrase, these passages were clearly marked as such and had to be translated accurately, leaving very little room for liberties to be taken, except one: I had to decide which one of the many official translations of the Bible to use. There’s the classic, old-fashioned, and dignified King James Version; the simpler, more quotidian New International Version; the conceptual, paraphrased New Living Translation, and so many others.

There were many aspects to consider when deciding which translation to use: I had to factor in which translation best fit the style of the book, which conveyed the contents and meaning of the passage most clearly, and how seamless its inclusion in the original work would be.

Then there were other questions, which further complicated my choice: certain Bible passages were presented as standalone pieces in the beginning or end of a chapter, filled with importance and significance. For these, it made more sense to use a biblical-sounding translation such as King James. Others were implemented into the text, contained within a non-biblical dialogue or description, and, though the language of the book is quite epic, still required some simplifying in order to be smoothly planted in. I wondered: would it be acceptable to use different translations for different quotes? I’m not sure why, but I felt uncomfortable about this, as if using biblical translations required a more rigid commitment to a single source.

Then another question came up: what if I found a translation that was appropriate, but changing a conjunction here and there would make it fit more seamlessly into the text? It was immensely tempting, as a translator, to make these kinds of changes, but even though it felt more permissible than if I were quoting a contemporary piece of writing, even though I didn’t think anyone would challenge me on it, the idea seemed immoral.

I decided that I would use the King James Version for the most part, opt for other translations when King James proved too antiquated, and refrain from altering whatever translation I choose. However, later on, the editor suggested switching all passages to the New International Version, and I agreed with a certain measure of relief. What these lacked in gravitas they made up for in ease of implementation. They were smooth and easy, more everyday than biblical sounding, and I accepted that they made a lot of sense for a contemporary biblical novel.

These days, I’m translating another novel, The Third by Yishai Sarid, which is a post-apocalyptic dystopia set in the resurrected Kingdom of Israel. Once more, I am faced with the question of how close to bring the content of biblical passages to the literary language, and of whether to match the language of the story to that of the Bible. In this novel the language shifts and vacillates between old-fashioned pomp and mundane modernity, just as the different translations vary in level of diction, presenting an additional challenge. Whatever I end up deciding, the question of biblical translations will always present a challenge whenever it comes up.