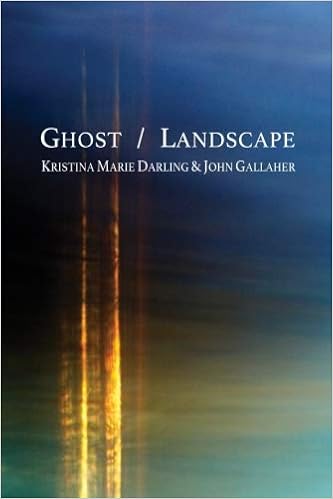

Review: GHOST/LANDSCAPE by Kristina Marie Darling & John Gallaher

Ghost/Landscape

Kristina Marie Darling & John Gallaher

Blaxevox, February 2016

102 pp; $16

Reviewed by Jennifer MacBain-Stephens

In the collaborative poetry collection Ghost/Landscape (Blazevox, 2016) by Kristina Marie Darling and John Gallaher there is no beginning or end. The first poem is “Chapter Two.” So begins traversing a time loop of poems where the reader can really “begin” anywhere. What is a beginning and what is an ending? Is moving forward and looking behind you the same thing? A circle never ends. “Chapter Two,” begins like a bed time story:

“We must have known there was no going back…that morning, before our windows had been broken, you asked about the lock on the door. I realized it was only a matter of time before the alarm sounded, which always seemed out of place in the dead of winter.”

The reader is a happy prisoner in this manikin-like frieze: feelings are suppressed into the pages of Goethe novel. Timelines, like broken glasses, need to be glued back together. If the reader needs to assemble a puzzle to establish a linear map, one should look to the corners first. In Ghost/Landscape, the edges are gray and decrepit. The backbone seethes.

Darling and Gallaher use color to drip the poems in surprising apathy. In this illusion to the underworld, “Thermopolis as a concept” they paint this canvas:

“The scenery is used to being blamed for such things, red,

beige, and more red with some yellow. And blue and black

and white.I’m busy looking at everything I’m looking at. It rises and falls as I sit and stand. It’s shadowy or bright or neither, really. Navys and grays. I expect great things from it.

A little jump and it’s leaping. There on the bluffs overlooking

the town I see it leap as I’m looking at it leaping.If, late in summer, it’s late summer, then it’s late in summer.

That weird feeling of being cheated when the forecast of bad

things happening doesn’t come to pass…”

The outer world is constantly in flux, unforgiving, and ambivalent towards the humans who gaze upon it no matter if the grass is green or covered in snow. There is also an apt correlation: if the outer surroundings are corrected than inner relationships may heal. In the poem “Landscaping,”

“We’re looking out the kitchen window, and we have this opportunity to go back and undo our errors. But where do we start? We mowed poorly around the trees. We didn’t marry well or have pleasant children…”

The landscape reflects a sadness. There are repeated domestic objects noted throughout the collection: drinking glasses, the phone, a calendar, a television, torn photographs. The objects reflect how the speakers convey the passing of time: selling them, losing them, realizing something was stolen. The objects may change but our connection to them remain the same. We sell certain objects just to want them again. In another poem in the middle of the collection, also titled “Chapter Two,”

“Next thing you know, the whole house is a yard sale. Your bed is three feet under other things. Here, there’s still some room between it and where the bureau was, a kind of depression you can lie on…”

The succinct wordplay here illustrates a heavy woe: one can lay down on a bed and make a depression with one’s figure as well as succumb to an emotional albatross.

In addition to reflecting the passage of time (and also the idea that time is stagnant by repeating certain behaviors,) the objects symbolically converse with the outer landscape.

In “The Chapter on Regret”

“I tried to phone you, but the snow went on for miles. That was the beginning of the winter, a year of thin trees and that odd silence…”

As a small child, I had always imagined unhappiness would be easy. Now the windows on our street darken like a kiss goodnight…”

The “snow” in the first line of the above poem references actual snow outside—where nothing green grows—and also the snow or static of a poorly connected phone call. The entire garden is covered in snow: no connection from the earth to air breaks through the frost, like no words warm the wires between two people.

In “Gardening,” this repeated line builds tension:

“That night I tried to phone you after the house fire and you didn’t pick up. That night I tried to phone you after the house fire and you didn’t pick up. That night I tried to phone you after the house fire and you didn’t pick up…” The only line about gardening are the last two lines: “They look for their shovels. One by one, they begin to dig.” The speaker confesses “I never kept a single flower alive.”

The language of these prose poems make up small movie sets. Each poem-scape possesses its own set dressing whether the space is in a house or a garden. But like the cliché states, a house is not always a home. Other shelters are described: a bomb shelter, that “extra room,” a haunted mansion. But who is waiting inside? Someone leaves for the city, but also confesses “I still see you there, in the yard.” The sets are routinely dismantled, (the objects change,) and the speakers are left holding a phone with no one at the other end.

If anything, Ghost/Landscape reveals how we maintain our emotional landscape every day, how we stammer to ghosts, desperate to connect even if it’s through the sound of breaking glass or looking into a cracked mirror.

Jennifer MacBain-Stephens went to NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and now lives in the DC area. She is the author of two full length poetry collections (forthcoming.) Her chapbook “Clown Machine” just came out from Grey Book Press. Recent work can be seen or is forthcoming at Jet Fuel Review, Lime Hawk, The Birds We Piled Loosely, Queen Mob’s Teahouse, Inter/rupture, Poor Claudia, and decomP. Her poetry reviews have appeared at TheRumpus.net and The Infoxicated Corner. Visit: http://jennifermacbainstephens.wordpress.com/.