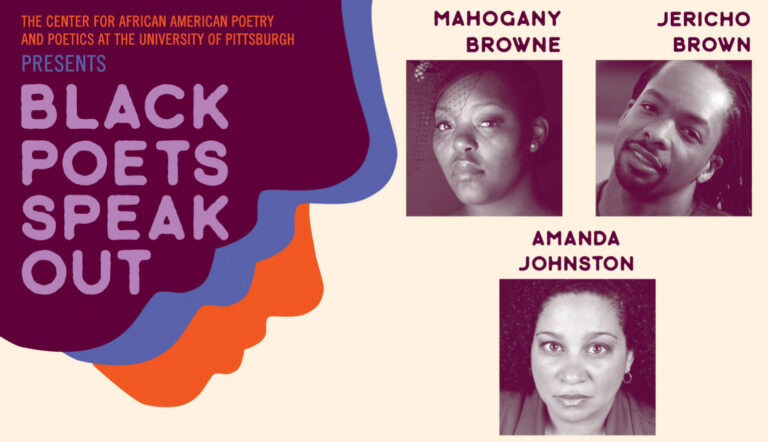

Couples, Talking (About Sex)

A funny thing happened to me this summer: I got trapped in the Sexual Revolution.

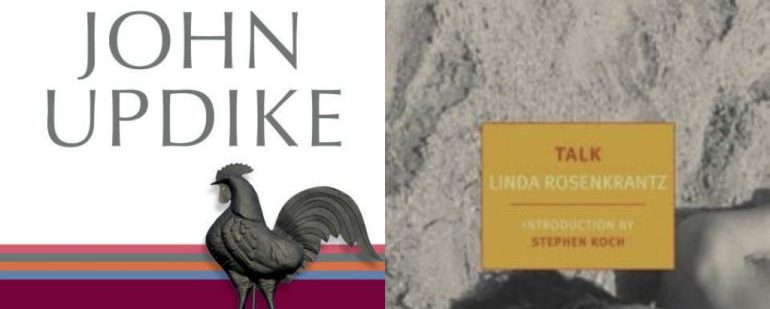

I don’t know how you read when you’re on vacation, but when I go away, I pack a stack of books and, instead of reading them one-by-one, I flit haphazardly among them, deciding each morning or afternoon whether I feel like reading about Victorian England or mid-20th Century New York or Mexico in the 1930s or wherever. But this summer, as I vacationed with my family on the Texas coast, I found myself moving back and forth between John Updike’s Couples and Linda Rosenkrantz’s Talk, two very different books that nonetheless barely required any mental traveling at all.

I chose Updike after reading this Meghan O’Gieblyn essay in the LA Review of Books. O’Gieblyn describes how, put off by the author’s well-earned reputation for sexism, she avoided reading Couples for years. When she did, she found in the novel (besides its misogyny) a compelling “document of one man’s fears about the limits of his dominion.” Talk had been on my reading list since Anna Weiner mentioned it in the New Republic as a rare example of a book that accurately depicts a variety of female friendship. As Weiner notes elsewhere, the book developed from transcripts of actual conversations Rosenkrantz recorded during the summer of 1965. Though it was originally marketed as a novel, Rosenkrantz was always uncomfortable with that designation, since she hadn’t invented any of her material, just edited transcripts down into a manageable narrative.

I picked the books up expecting difference. And they are very different. One is a prestigious novel in the traditional mold, meticulously plotted, with gorgeous descriptions of New England salt marshes and skies and deep, sometimes heavy-handed symbolism. The other is an experimental work that washes over you like a night of great conversation, leaving only impressions about personalities and a few kicky turns of phrase.

Still, I could not have anticipated how thoroughly the two works would overlap. Both were published in 1968 and set a few years before that. Both are focused on the leisure time of white, educated young-ish people just past or just about to reach their 30th birthdays. And in that leisure time, those characters do similar things: sunbathe, throw boozy dinner parties, play parlor games. In fact, characters in the two books play the exact same parlor game, in which one character has to guess the identity of an acquaintance or celebrity by asking strange questions like “What time of day am I?” or “What country in Europe would this person be?”

The biggest similarity between the two books, though, is their concern with shifting cultural attitudes toward sex. As O’Gieblyn writes about Couples, the book “landed Updike on the cover of Time and sparked a fury of handwringing about the country’s loosened sexual mores.” Talk didn’t receive the publicity Couples did, but must have been just as shocking to its readers—characters speculate about the relative merits of orgies and threesomes, recount their most “perverse” sexual experiences, and consider the happiness (or not) of a couple in an open marriage. “We’re all pioneers going through new frontiers, new jungles,” says one character in Talk, in a line that could have come from Couples. “We’re breaking psychic, social land so that people following us will be able to lead better lives.”

But it’s precisely these similarities that make the novels’ differences matter. Because, while I agree with O’Gieblyn that Updike deserves to be more widely read than he is now, it’s also true that Talk, which has been compared to Girls and to Broad City, feels much fresher than Couples. When I tried to figure out why, the answer I kept coming back to was the space between the novels’ perspectives. Couples tells the story of the Sexual Revolution as understood by a heterosexual man of that time. It’s focused on the perspective of a male character, Piet Hanema, who sees the promise of the “post-pill paradise” as a chance to jump from bed to bed without consequence. Talk tells the story of the same era from the perspective of two women and a gay man. That shift makes all the difference.

For Updike, the revolution meant the enshrinement of sexual pleasure as the highest ideal; in interviews, the author said that he wanted to explore in Couples the idea of “sex as the emergent religion, as the only thing left.” The characters in Talk, in contrast, don’t take sex so seriously. When Marsha (a stand-in for the author) describes her S&M experience with a previous boyfriend, she emphasizes its humor. “It was very funny,” she says, “I mean here I was in this ludicrous position and he’s going through all these things, he had lotions and potions that he rubbed on all my sensitive areas, wintergreen oil that athletes use, and he’s running around very busy, busy, busy.” And then: “To tell you the truth, I didn’t find it that sexual.”

In Talk, the revolutionary aspect of the Sexual Revolution isn’t the possibility of unlimited pleasure—it’s the possibility of everybody having a voice regarding sex and sexuality. That’s what Updike missed about the Sexual Revolution, and that’s why Couples feels so dated now. O’Gieblyn describes Couples as depicting a “glinting moment in time” when swinging and open marriages seemed “like something everyone should be doing and from which no ill consequences could be conceived.” Fifty years later, it’s hard to believe anyone really believed that, or that Updike felt the need to devote an entire novel to debunking it. The characters in Talk could have done the job with a couple of wisecracks.

What was the meaning of the Sexual Revolution? There are still people who hold Updike’s view that the whole era boils down to the institutionalization of “if it feels good, do it.” But reading Couples alongside Talk shows that there was more to it than that—if the Sexual Revolution still matters today, it’s because all of the social changes of the 1960s gave us new ways to think about who has the right to talk.