Reading Ondaatje in the Age of Trump

During a school presentation meant to illustrate the awfulness of the apartheid regime, we were told to split – white children on one side, black children on the other. I’m what is called coloured in South Africa – a person of mixed racial heritage, encompassing Khoi indigenous, Malay (from the Malay slaves brought to the Cape), black African, and European ancestry. In my case this is also mixed with Indian heritage, from the indentured Indian workers brought to South Africa by the colonists. Sometimes I pass for white, sometimes I don’t. Sometimes I’m just assumed “foreign”. So when told to choose a side, I stood resolutely in the middle of the aisle between the two groups of seats and stared indignant at the presenter. Needless to say, it didn’t make much of a point and I was summarily told to “just sit on the black side”.

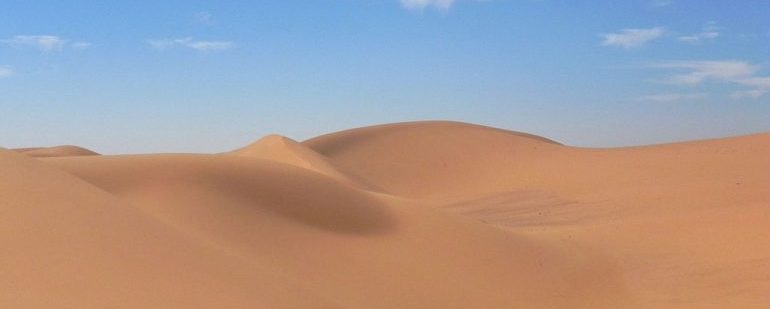

Around the same time, I read Michael Ondaatje’s “The English Patient” for the first time. “Gradually we became nationless. I came to hate nations. We are deformed by nation-states… The desert could not be claimed or owned — it was a piece of cloth carried by winds, never held down by stones, and given a hundred shifting names long before Canterbury existed, long before battles and treaties quilted Europe and the East… All of us… wished to remove the clothing of our countries. It was a place of faith. We disappeared into landscape.”

I wanted to undo the demarcation of loyalties, of heritages, nationalities, that bound me up and decided for me what to give my heart and life to. As I grew up, this shifted and changed. Even now, as an ardent intersectional feminist, I hate with all my heart calling myself a “woman of colour”, a “South African”.

I hate it because it imposes so many sets of assumptions, so much arrogance. How can I talk for other “women of colour” when I’m not them? When we have an infinite range of other characteristics that inform our lives? In the age of Donald Trump, of Brexit, of a refugee crisis that is a key force governing international decisions — nations, demarcations of identity, loyalty, apparent belonging are the lifeblood of political discourse.

And I despise it. I want to reject it on a visceral level, to “walk upon … an earth that had no maps.”

I am surrounded by images of refugees drowned in the Mediterranean, tortured and raped at the borders of countries because they needed to cross those borders, of Donald Trump, and his supporters shouting Sieg heil, of “Britain First” Brexit campaigners and what violence they mean for so many. People’s homes and beloved places are blown apart by drones, taken by “settlers”. Discourse in South Africa – ‘my country’ – is centred on demarcations of identity that apparently govern who has a right to say what, and when, and how, with little thought given to the complicated, human ways in which people live and navigate the world. I am disgusted, repulsed by how even in fighting a colonial legacy we use the same tools to reduce and decide and organize hierarchies and loyalties.

In Ondaatje’s book, he says, “There was a time when mapmakers named the places they travelled through with the names of lovers rather than their own. Someone seen bathing in a desert caravan, holding up muslin with one arm in front of her. Some old Arab poet’s woman, whose white-dove shoulders made him describe an oasis with her name. The skin bucket spreads water over her, she wraps herself in the cloth, and the old scribe turns from her to describe Zerzura.”

In considering the cosmopolitan ethics espoused in The English Patient, John U. Peters quotes E.M. Forster: “I hate the idea of causes, and if I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.” There are things dearer, after all.

My husband is a white man. Some of his ancestors, in fact, ran the Dutch East India Company, responsible for bringing many of my ancestors to the Cape as slaves. There are times when the world’s past and present come up between us like a sore, when racism and privilege set us on either side of a divide we have to reach across, with tenderness, with silences and long discussions, sometimes tears. Sore places where the world has made us sore. But love makes the way across. His face is dearer to me than all of history. His laugh more familiar to me than any loyalty to a cause or border. I turn off the news, turn off my phone, and we lie in the sun, we make dinner, we water our little basil plant and our little olive tree.

We sing songs in Arabic and Afrikaans, Yiddish and Spanish. We learned them from all the people we love, the ones who have eaten and laughed and wept with us. This is how I want to mark the world, the seas and times – by loves and friends, more real to me than what we are on paper, by which line we’re forced to stand in.