“frank ocean and all black things that disappear on their own”: A Conversation with Jonathan Jacob Moore

Jonathan Jacob Moore is a poet, critical thinker, and scholar whose work online and in real life engages questions and realities of blackness, queerness, performance, and their intersections. As a student at Tufts, his visions collaborate across various media—page-poems, tweets, response memes—to explore and revise the status quo of pedagogies, oralities, and what can be communicated and felt. Simply put, he’s Doing the Work, mostly under the handle @hoodqueer

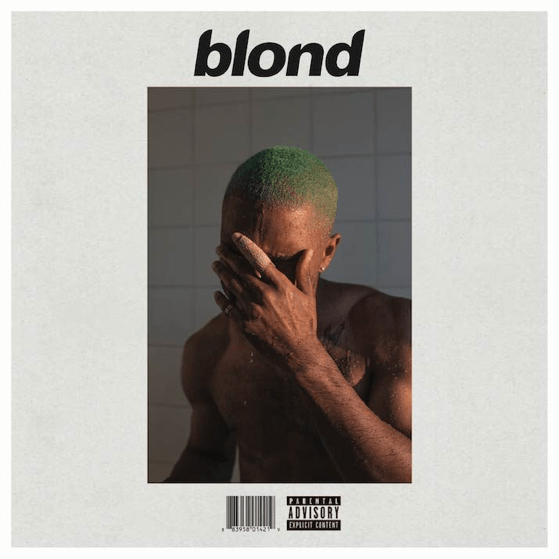

Typically, I use this feature to briefly analyze and boost a poem each month. But, due to the circumstances of this past August—that Moore was writing about the new Frank Ocean album, and that the music recently, finally, came out—I decided to follow up with Moore about his work as a chance for us to publicly organize and present our thoughts on Frank Ocean and Moore’s poetry.

John Rufo (JR): I am interested in the possibilities of your poem “frank ocean and all black things that disappear on their own”—recently published in The James Franco Review—as a double-edged ekphrastic sonic queer project.

The first, maybe obvious question is: How do you feel about this piece of writing now that Frank Ocean’s albums have been released into the world? How do you consider your own art object, previously in relation to an imaginary or not-yet-born art object, now that the album is live, a living, listenable?

Jonathan Jacob Moore (JJM): I wrote the piece at the height of the very public, quite divergent, and mad emotional conversations among Black folks awaiting the release. I was fascinated with Frank Ocean “the Black-Artist-On-Sabbatical”: checking Twitter when he trended, clicking links that led to nowhere.

When the work was finally made available, I felt the displacement of great anticipation. I had jumped on the Frank Ocean rollercoaster without knowing where I was headed—just that he mattered enough to evoke Black meme production, a definitive signal to tune in and be blown away. The spectacle continues to be riveting: to be a part of Black public performance that was the innumerable countdowns, foolhardy threats, and apologies (i.e “If you don’t drop this damn album tomorrow I’m deleting your number out my phone . . . jk you wild wyd”). This intimate-ass relationship between Frank and Fans (which intensified with every failed deadline to “deliver”) captivated me and informed the poem. “frank ocean and all black things that disappear on their own” now works in the shadow of the new music as opposed to its absence, though remains invested in the (plentiful) absence of Frank Ocean “the Artist.” It still has questions for him. It’s no less insistent, no less curious. It’s still asking, “Do you hate coming outside, sometimes?” and reciprocity now imagined with Frank Ocean “the Black-Artist-Returned.”

I’ve found that the libidinal economy of the Black twittersphere, the intellectual game of the academy, the inimitable intimacy of ten or so poet friends reading my work online: these all produce different relationships between the text and myself. The art object is created to be (in)accessible in different ways and not always consciously.

I’m thinking now about Blond(e) and the lurching accessibility it can offer up as music—from roaring overture to Black boy confessional, jokes between friends to smooth-ass esoteric declarations of love. What it feels like: being in the passenger seat with a driver new to stick shift—more fun for them, maybe, than for you. It mimics the quotidian (in)stability of Black life.

JR: The poem directly addresses and acknowledges a “you” that’s assumed to be Frank Ocean, but do you feel like the poem encompasses other possibilities for this second-person? Essentially, I’m asking how you think this poem extends beyond Ocean, as its “you” either taking into account the speaker as a potential “you” or the second half of the title “and all black things that disappear on their own,” with “on their own” and self-agency especially underlined?

JJM: Yeah, totally. The possibilities for the second “you” is as open-ended as it is dialogical. Frank’s absence spurred all different kinds of thoughts for me—mostly around choice, absence, expression and space—some of which had to do with absence and suicide. While I withhold the narrative fact of suicide, it viscerally interrupts my defense of Frank’s absence:

you deserve time

before the proverbial train hits

and the album drops

The speaker’s identity is refused explicitly and can be read in varying lines; the I of Frank, the I of the reader, the I of author. In thinking about the train making contact with the body and the album being made public as “choices,” contextualized within the virulently anti-Black world, I aimed to elide the living and the dead. I’m thinking “What is the compassing effect of anti-blackness on art and expression in life and death?”

Most would argue that Frank’s fleeting break from making (public) his art was a choice in the common sense understanding. Try to unsettle that assumption: just as I call into question the ethicality of condemning (or even mourning, in the common sense understanding) Black people that choose to end their life on this planet. What are the ethics of beating an anti-Black world to the punch: what does that look like?

JR: This idea of the elision of death/life, I think, relates to your line “because the hook would Sodom and Gomorrah us”—as it conjures (at least) two ideas: one, of “dropping bombs,” like Funkmaster Flex, the hit single debut on radio made public, but also of an obliterative queerness: a totalizing response for a kind of anti/or non/-normative sexuality (as in the story of Sodom and Gomorrah and its subsequent public punishment) but also as a means for indicating Ocean’s own public/private ways of negotiating and performing his sexuality and blackness. That is, the music itself is in dialogue with varieties of queer being.

JJM: It’s a favorite line of mine as well, because it’s in conversation with Ocean’s evocations of God while putting the biblical story on its head. The Sodomite is in the driver’s seat . . . so where we going? The question becomes, “What does Frank know that we don’t?” I see him, in absentia, harboring not some scandalous secret but an unbearable truth—some sonic engendering, some hook that can ungender and unhinge the taken-for-granted dynamics between Black people, time, and space.

That said, to think for a moment about expressive blackness as that obliterative queerness threatening the world’s destructive present is a flirty project of futurity. Speaking of flirting, Frank’s performance has helped me think through refusal (to identify, to be present, to be) as an impossible indulgence. After “Forrest Gump” queered Frank Ocean the Artist, I think some expected him to intensify lyrical elaboration and personal identification with Queerness®—and, for the most part, he has refused the charge. I’m all here for it.

Whereas Black sexuality is public property ipso facto, I think Frank looks the specters of “the gay rapper” and the “straight faggot” in the eye and calls their bluffs. It’s messy and rightfully so. The Black body is always-already fucking at all times: on Blond(e) and Endless, Frank isn’t a stranger to this reality. He’s producing art in the thick of it. As a Black bitchboi, when I hear his lines, “I’d rather live outside, I’d rather live outside, I’d rather go to jail, I’ve tried hell,” I don’t think gay marriage and designer puppy. I think frustration. I think depression, I think insanity. I don’t think alienation—I think existential exile. In “Futura Free,” he gives us this: “Let me run this bitch / I’ma run it into the ground momma, the whole galaxy.” Running the world into the ground isn’t just a question of aesthetics. It’s an invitation—towards what, exactly, is something my poem refuses to answer.

His obsession with cars, Frank writes, is related to “straight boy fantasy.” “Consciously though,” he says, “I don’t want straight. A little bent is good.” What the fuck does that mean? Frank’s queerness is just that: a little bent, a little left to be determined, a little unknown (even to him), and that’s all I need to know.