Githa Hariharan Talks Indian Femme Fatales and Politics

Part anthropological, part historical, Githa Hariharan’s writing takes readers across the globe, through history, and into dense political arenas. Her novels and nonfiction marry experience and intellect in sometimes biting, often lyrical prose. Whether she’s reshaping Shahrzad and The Arabian Nights or shedding light on censorship and fundamentalism, Hariharan’s stories are often led by femme fatales

with political prowess. The promise of a bumpy ride continues in her memoir/travelogue, Almost Home: Finding a Place in the World from Kashmir to New York, published earlier this year by Restless Books.

A collection of essays, Almost Home is a wonderland of hybrid techniques. It contains post-colonial insight that goes beyond India and keeps readers coming back for more—more labyrinthine story lines, more social commentary, more pro-woman eroticism. Hariharan’s other popular titles include In Times of Siege, an exploration of religious censorship in literature and education in today’s India; When Dreams Travel, a work of haunting historical fiction with femme fatale protagonists; and Fugitive Histories, in which she explores social issues in modern India without catering to Western expectations.

Having broken a knee and ankle in an accident in Manhattan, she cut short a recent press trip for the U.S. release of Almost Home. We caught up while she was recuperating—and conducting activist duties—from her Delhi bed. Some of the topics up for grabs? Nationalism vs. patriotism, how far behind the US lags in international literature, and the American Presidential campaign.

Nichole L. Reber: One thing I’ve noticed in reading Indian authors is an exaltation of female protagonists. Your work certainly does this. Is there a historical element to this practice?

Githa Hariharan: I can’t resist being a little sarcastic about this. The “historical element” is one strand of Indian culture that continues into the present: deifying women so they become “goddesses” rather than citizens with equal rights.

At any rate, it’s hard to make a generalization about “Indian authors,” because there are several Indian literatures and traditions in many Indian languages. I can say with greater confidence that many women writers have taken up what is often perceived (wrongly, I think) as the smaller canvas—women’s lives, whether they are middle class, or marginalized in terms of caste and community. I want to underline this point about diversity of takes within that troublesome description of what is “Indian.”

As far as my own work is concerned, the great ideas of our time, including the notion of the unconscious, interpretations of class struggle and feminism, inform my work as they must so many other contemporary writers. I am a writer though, and my novels, stories and essays are not feminist tracts. They take the ideas I feel strongly about, and embody them in real people, real life situations. You could say I am concerned with how we live both equality and inequality in real life; or how we live the many ways in which power struggles work out.

NLR: What contemporary authors do you read from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and/or Sri Lanka?

GH: Sadly, I can only read translations into English, or what is originally written in English. My list of Indian writers is, naturally, a long one. It includes Malayalam writers Paul Zacharia, O. V. Vijayan and Sarah Joseph; Tamil writer Ambai; Bengali writer Mahasweta Devi; and writers in English such as Kiran Nagarkar, Nayantara Sahgal, Amitav Ghosh, Ranjit Hoskote and Shashi Deshpande. I enjoyed Tahmima Anam’s novels on Bangladesh; from Pakistan, I enjoyed Mohammed Hanif’s The Case of Exploding Mangoes and Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist. All these, of course, make up a small part of my list!

NLR: Can you explain the process of bringing a version to American bookstores?

GH: We writers always want readers. Our writing is incomplete without a readership. But the international marketplace (read: mostly the US and UK) is a difficult beast to conquer. This is especially true if you are writing about what you know best; not making concessions to what that particular market wants; living at home; and, of course there may be an element of luck. My experience is that despite good agents, the American market prefers something comprehensible as “Indian,” or something with an overt American link. Globalization has not really brought the “international” to America on equal terms. The universal is still parked in the Western metropolis; and what the rest of us write, living elsewhere and rooted in that location’s perspective, tends to be viewed as writing by native informants.

But many writers from other parts of the world are confronting this, and perhaps the excellent niche market publishing ventures in the US will grow in strength with all our books. All said and done, you do feel a bit like an “other” because mainstream publishing in the US is still conventional. Whatever it is, not one of us is going to stop writing about the world at large, wherever we come from and wherever we live.

NLR: As a writer and someone who covers international literary culture, I’ve wondered to what extent authors from around the world feel a need to write of particular topics or use certain techniques to appeal to a Western or American audience.

GH: All authors care about their books reaching people, crossing borders. But that is after the book is written, and is independent of the author and the writing process. The actual writing suffers, I think, if you worry about who is going to read it.

While writing, you cannot think about nationality. You write for yourself, people like yourself, and maybe people who are from anywhere or from any time in history, but who you admire and want to speak to as you write. Writing for a particular market would kill me as a writer. You can always make minor edits if there is something that needs to be made legible for readers from elsewhere. But you cannot change the basics, and you need not over-explain. After all, the colonized have always done a good job of reading and understanding texts from a different culture!

NLR: Have Western publishers ever asked you to change your work to make it less “ethnic.”

GH: No, I have not, though that could be one reason why some of my books have not been published in the US. But I must add that I have been told, both in the UK and US (as well as India!), that perhaps I should stick to writing on “Indian” matters. This happened with my essays in Almost Home. But for me, seeing the world as a cosmopolitan Indian is very much an “Indian” matter.

NLR: What’s the difference between nationalism and patriotism? Could it be that people who have traveled or lived around the world are more apt to see their countries more objectively than those who’ve never left?

GH: Many of those who are screaming about a distorted form of nationalism and patriotism in India have traveled widely; a few have been to Harvard for what that’s worth. It’s a question of post-colonial India losing track of the inclusive nationalism, which fueled the freedom movement against the British colonials. The freedom movement did not exclude women or Muslims or the “lower castes.” Our constitution was written by the great Dalit leader Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. And now, all these years later, nationalism has become an exclusionary thing: to ask questions, to use your brains independently, has become “anti-national.” As for patriotism, history shows us how this concept has created wars, enmity, walls—you are not rationally patriotic simply by differentiating yourself from the people of other countries, dehumanizing them, or being scared of them. This sort of patriotism makes no sense at all to me.

NLR: A number of sentiments from In Times of Siege sound like they could have come from the speeches of Donald Trump, especially for their theocratic and fascist strains. Then again I think you captured political strife and even political celebrity so articulately that the sound seems timeless. This story could be told from many perspectives: the current Syrian crisis, Trotskyism in Russia, and political coups in South America. Have critics or fundoos, as the female protagonist calls them, made your life any tougher since writing this?

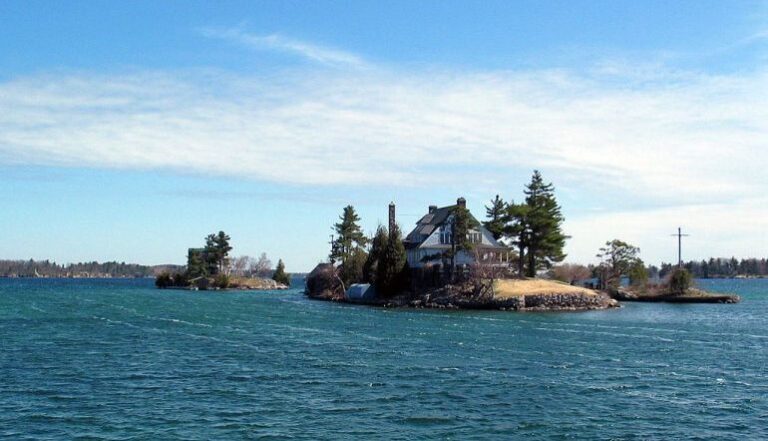

GH: As I was writing the novel In Times of Siege, there was an incident in India which made me feel reality was snapping at my heels as I wrote fiction. The work of two respected historians on India’s freedom movement was targeted by the fundoos. Then the US invaded Iraq, and siege became a metaphor and a reality in a larger space. Since then, siege has been an ongoing state in so many parts of the world, whether in Palestine, Iraq, Syria or Afghanistan, to name only the most obvious. The list grows; it seems endless. With Trump-speak and Modi-speak, our sense of being besieged, whether in India or the US, is perhaps being articulated in new forms. It’s not just the individual that this alerts us to; it’s the exclusionary ideology that seeks to divide people. That ideological voice has become that of the “acceptable fundoo”. But they live on the island next door to the other obvious or “overt” fundoos such as the IS or al-Qaeda or Taliban.