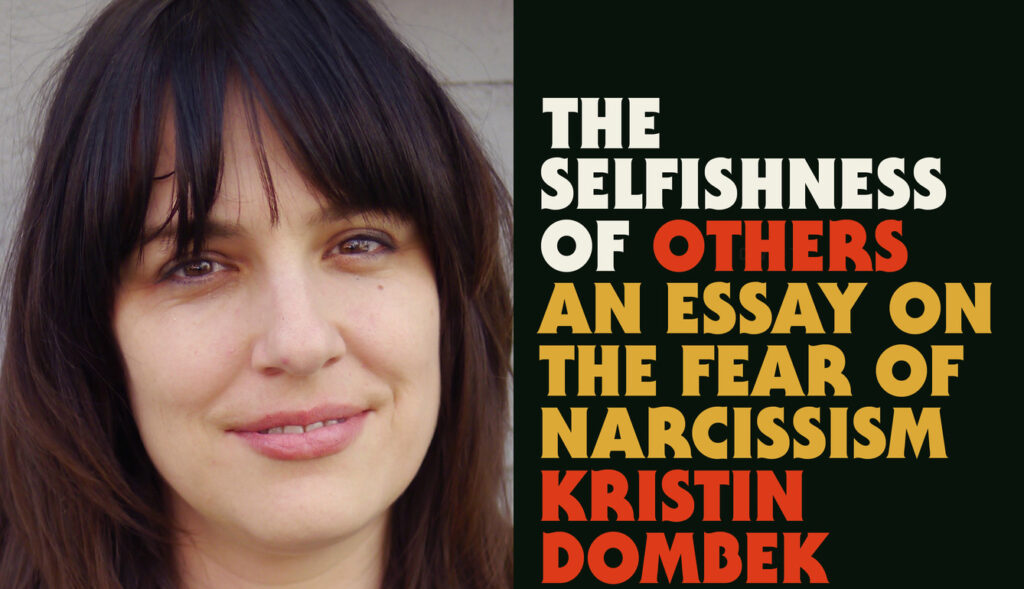

Interview with Kristin Dombek

Last month at the Franklin Electric Reading Series in Crown Heights, Kristin Dombek read a collaborative “choose your own adventure” piece with her friend Stephanie K. Hopkins, pausing after every scene to ask the audience where the story should travel next. It showcased the best aspects of Dombek’s work, the heavily architected pieces that simultaneously make her vulnerable to the reader and invite collaboration in an argument. Whether she’s writing about the gentrification of Williamsburg, prayer and polyamory, or why it’s cool now to “try hard,” Kristin Dombek writes exactly the kind of essay I want to read: pieces that balance her substantial critical faculties with a rare personal openness.

In her first full-length book, The Selfishness of Others, an examination and refutation of the American narcissism epidemic, Dombek’s generosity and clarity of thinking are on full display. The book is her most expansive, wry, and rigorous work to date. She demonstrates compassion for the selfish among us, and saves sympathy for us at our worst, when we’re fearful of others’ selfishness. She writes “The selfishness of others is the feeling of your dependence revealed, as their gaze turns away. Your independence laid bare as a myth. The feeling of being the animal you are, born of other animals, made of mirroring them.”

Dombek’s work has been featured in n+1, The Paris Review, The New York Times Magazine, and Harper’s Magazine. The Selfishness of Others: An Essay on the Fear of Narcissism was published by FSG Originals. I spoke with Kristin over email about her writing process, how over-diagnoses can evidence social change, and whether she gives a shit about what other people think.

Laura Creste: What first compelled you to write about narcissism? I’m wondering what piqued your interest, or where you found an entry point into this pervasive subject?

Kristin Dombek: A few years ago I started hearing the diagnosis of “narcissism” a lot in casual conversation, saw it scrolling down my screen. And it seemed sketchy to me, the word, so I got curious about it. It’s a particular kind of judgment, about a person empty of empathy, so self-absorbed as to seem fake. It’s applied to memoirists, people who write from the “I,” so that challenged me. But like “terrorist,” or “delusional,” it’s a word that’s used in ways that seem quite relative—the narcissist is always an ex, or a person or group you disagree with, or the whole younger generation, if you’re older. I’d used it in these ways myself. I got interested in looking at the fear that more and more people are evil and fake, lacking empathy. To me, that fear seemed like a clue about what keeps us from trusting others, on a personal level but also on a more global level.

LC: You mention in the book that narcissism accusations have historically been gendered, and that the label gets volleyed back and forth between genders depending on the cultural moment. Is being accused of narcissism something of a backwards compliment, a reflection that your interests have been recognized, that you’ve achieved social or political power?

KD: That’s a great way to put it—I think it can be, yes. Not always. Sometimes it is a word that helps you define the ways in which someone is being abusive, and why you must disentangle yourself. But “narcissism” is a word that’s sometimes used to assert a diagnostic power over someone, or a group of people, who are perceived as having too much, or asking for too much. When I started reading, I noticed that Freud’s narcissists were women and gay men. As I was writing, others published deeper research about this. The historian Elizabeth Lunbeck’s The Americanization of Narcissism tracks how, in psychoanalysis, “narcissism” was a construct that helped to pathologize homosexuality and femininity. In her review of that book, Vivian Gornick wrote about marching for equal rights, in the 70s, and then having Christopher Lasch condemn feminism as narcissistic. You say “we’re here, too,” and someone whose power is threatened is going to say “you’re too self-absorbed.” The book launch for The Selfishness of Others was in a historically African-American neighborhood, Ft. Greene, from which so many have been displaced, and the majority of people at the launch looked to be what we call “white.” During the Q & A, a person of color in the audience pointed this out, and afterwards about twenty white people came up to tell me they thought that person was a narcissist, for “interrupting” the event to talk about this. So in that way a valid intervention, an important one, is dismissed by claiming the person who makes it is vain, and self-absorbed, or worse, has a mental illness.

LC: I love how the essay allows for a casual and intimate tone, even though you’ve largely omitted the first person mode that’s served you loyally in past projects. Do you see The Selfishness of Others as being in conversation with other books?

KD: Thank you. I’m glad you find it so. Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer and J.M. Coetzee’s The Lives of Animals were on my mind. Short books whose argument, or understanding, comes as much in the form, as in what’s said. And I wrote it literally in conversation with my friend Stephanie K. Hopkins, who wrote her memoir of an open marriage at the same time, right next to me.

LC: You’ve written before about polyamorous relationships. Can you talk about the intersection of self-interest and polyamory? Relationships with multiple partners seem to require a real lack of selfishness, and a faith in one’s ability not to become jealous.

KD: I don’t think having an honestly open relationship is necessarily any more selfless than monogamy, or, say, raising children. But there is something that’s different, in my experience, and it’s more about space and time. And in the beginning, this essay, and my suspicion of “narcissism” as a stable category, did come very much out of the experience of being in an open relationship, though the writing that explained that ended up getting cut. When we have relationships end-to-end, one at a time, one or both people often ends up getting called selfish, or seems to turn fake or even evil, in the end. You see their selfishness, and they your own, over time. So everyone’s ex is a narcissist, or seems like one, for a while. And then sometimes years later you get a perspective on why they were acting the way they were. But when you more than one relationship at the same time, transparently, you kind of get a sense for how relative the term can be. So that if you are, just hypothetically speaking, in a relationship with a woman and also in a relationship with a man, and you love them both, and one of them feels you’re selfish because you’re spending too much time working on a book about narcissism, and you think the other one is selfish because they’re spending too much time with their other partner, it kind of trains you to recognize how it’s not necessarily about you, when someone turns away, or about their having some kind of disorder.

LC: What were some of the challenges to writing in the third person, and in having a more academic focus than the personal essays you’re best known for?

KD: Writing without the “I,” for most of the book, I learned a lot about what it’s useful for, in nonfiction. The “I” can make it easier to ask nuanced questions, show humility, show how limited and tentative our thinking is, create intimacy, stage contradiction, reveal the commitments that make us argue what we do, articulate the body, cry out against injustice, demand our local experiences be treated as real, take responsibility, clarify which ideas are ours and which are others’, wonder and not-know (rather than asserting that we know), change our minds, say “this is just me” so the reader can understand as she will, ask for empathy, ask for trust.

LC: What is your writing ritual like? (Coffee, tea, wine? First drafts in longhand or on your laptop?)

KD: All those beverages, definitely. I think the most important element is friendship, though. There are long periods of solitude, but on the best days, I’m writing near a good friend or two, or near my partner while he’s writing songs or mixing, and we’re reading and talking about what we’re working on and playing music at the end of the day. I wrote most of this book in the home of Stephanie and her wife, my friend Dawn Lundy Martin, a beautiful cabin in a Long Island woods.

LC: What does it mean to be brave or personal in an essay (or any writing)?

KD: Not giving a shit about what people will think, while at the same time making sure that the stuff that you’re not giving a shit about actually matters to more people than yourself.

LC: One of the questions in the Proust questionnaire is What quality do you most deplore in others? Perhaps many would answer some version of “narcissism” or “selfishness” as a result of the cultural moment we’re living in. What’s yours?

KD: Honestly, selfishness. Which I would define as: the feeling of scarcity that is inevitable, for most people, given the inequality of our time. But I deplore the systems that pit us against one another, more than the people themselves.

LC: What were you like at sixteen, the age Allison was when her MTV special was filmed, which you cite as an example in your book?

KD: I was in college; I’d been homeschooled in grade school and skipped a grade, so I went early. It was my first time away from the Indiana farm where I grew up. I never would have dreamed of throwing that kind of a party, much less on television, if there had been the money. We didn’t even own a television. I was shy and nervous and very religious. I read all the time and lived through books. I explained this to Allison, when we talked, in order to ask her—what was it about the way you’d grown up, that made you want to do this thing? For her, things were different. Fabulous parties were a regular family event.

LC: What are you working on now / plan to write next?

KD: I’m working on a book-length expansion of an essay I wrote for n+1, “How to Quit.”