There Are Places I Remember: on the Fine Line Between Fiction and Memoir in Translation

Sometimes it feels as if I’m not merely translating people’s stories into English, but helping people preserve their own lives, turning them into internationally comprehendible keepsakes.

For every two books of pure fiction that I translate, there is a third that is not exactly a memoir, not exactly a biography, but a novelization, an imagining, of true events that occurred in an author’s family. These are usually authors in their sixties or seventies writing about their parents’ lives or their own childhood memories. They have a deep pool of family lore and anecdotes to draw from, have performed extensive personal and historical research, and have utilized their own powers of imagination to fill in the missing details.

Many of us who write make use of our own lives or the lives of those around us. I know it’s always been a great comfort to me, in times of familial turmoil, to say to myself, “I get to write about this later.” There are certain people in my life whose histories I simply can’t let go of. They permeate my fiction, offering themselves up for me to use as I please. I can take a few unpleasant things that a bunch of different people did to them and squeeze them into the actions of a single character, thus creating a villain. I can insert myself into their stories or bring their stories into my current life, or into any other setting I can imagine, and blend fact and fiction with sometimes seamless, always exciting liberty.

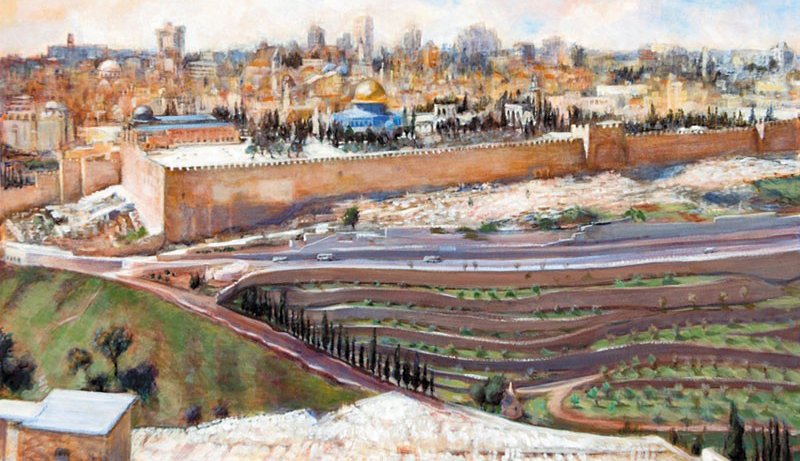

But these books that I’ve been translating a lot recently are trying to do something else. Though they make use of the art of fiction, fact is their focal point, and accuracy is their obsession. These stories are filled with details: the names of people, cities, schools, organizations, streets. The dates of births, deaths, wars, marriages. They are a labor of love, with labor being the operative word; a careful and considerate report of private life. Of course, in Israel they are more than that. To older Israelis, the generation that either emigrated over from Europe or that was born in the country when it was not yet a state, these details mean the world. Those shtetls of ash and that country of dust were so small, if not in dimensions than in perceptions, and the people who were a part of them often remember each other by name even years later. To my grandmother, knowing the name of the Tel Aviv high school a character in a book attended means knowing whether or not they are a part of each other’s lives. To my grandfather, knowing the name of the small town in Galician Poland where a character grew up meant knowing if they had experienced the same pain.

But what does it mean to an English speaker reading the translation? That is the dilemma I’m often struck by when translating this type of book. My instinct? Not much. To a person who is not part of this story, a few specific details might be nice—they ground the characters in a specific time and place and they convey the sense that this is a true story, at least partially, and that it is meaningful because it is real. But for the most part, a foreign reader not only wouldn’t care about the name and correct spelling of a school or town; these details might in fact break a reader’s concentration. It would be difficult to be swept up by emotion when pausing every few minutes to strain one’s throat trying to pronounce these words, or strain one’s memory trying to keep up with everyone’s last names.

To me this is an obvious choice. But to the authors, whose family histories are on the page, who have often gone to the trouble of writing them down to honor the memories of their long lost loved ones, it’s often not an easy compromise. They need their story to be true. They need it to be their story. It is my job then to ease them into the process of considering their new readership, widening the lens of their perception of publication, and encouraging them into the prospect of seeing their story as one of general interest, internationally and humanly relatable. Once they realize that removing some of the details would make their foreign readers feel more, rather than less connected, and let them see the forest, as it were, they gain confidence and are happy to adapt. The result is a book packed with emotion, still strongly rooted in time and place, but one whose branches are free to sway in the wind.