Clearing off the Cobwebs: Seneca Falls, New York and the first Women’s Rights Convention

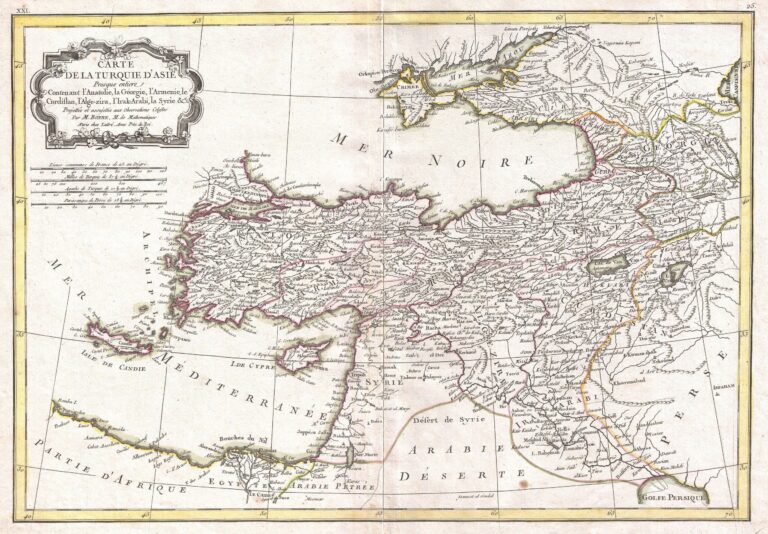

I was hopeful a few weeks ago, on Halloween weekend, when I drove to Seneca Falls, New York. There, in 1848, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and other reformers organized the first Women’s Rights Convention, demanding social and legal equality for women, including the right to vote. We had come so far since then, on the brink of a historic election in which a woman was a major party candidate.

The roadside was paved with yellow, orange, and red leaves, lined by pumpkin stands, wineries, and Trump/Pence signs. It was layered also with a history I mostly know about from books, starting with the Childhood of Famous Americans biographies I checked out from the library as a child about Stanton and Mott, writing by feminists like Margaret Fuller, and powerful speeches by Sojourner Truth.

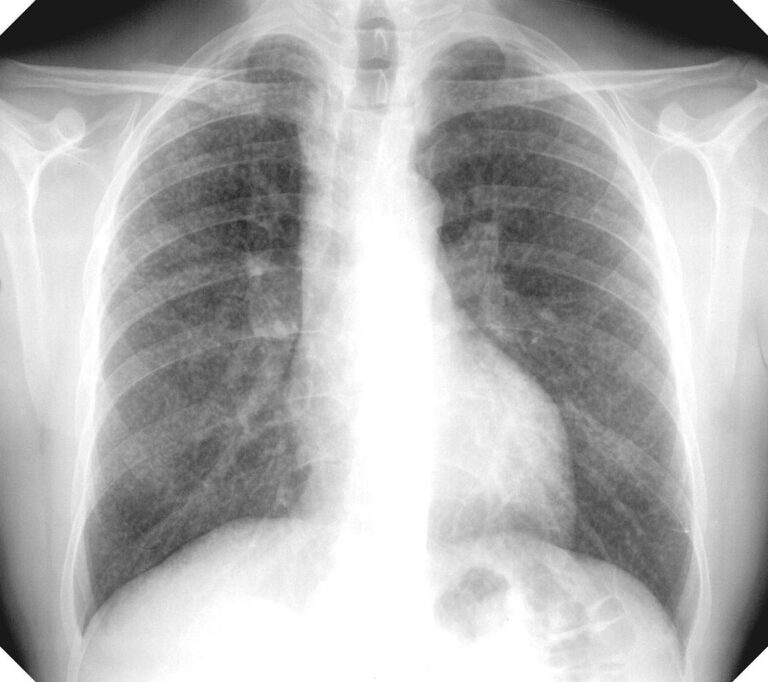

I passed through Geneva, the town where Elizabeth Blackwell, the first U.S. female doctor, got her medical degree when no other school would accept her, and imagined her strolling along Seneca Lake in 1847. Rochester was nearby, and the grave of Susan B. Anthony, who in 1873 was found guilty of voting without the right to vote. Now, on election days, women line up to leave their “I Voted” stickers on her grave. Also nearby, in Auburn, was the home that Harriet Tubman moved to in 1857 after delivering hundreds of slaves to freedom on the Underground Railroad.

Seneca Falls, also said to be the inspiration for Bedford Falls in the movie It’s a Wonderful Life, was hosting a Halloween parade that morning, and I arrived to find the National Women’s Hall of Fame decorated for the holiday. In its lobby, twenty bronze attendees of the Women’s Rights Convention, life-sized sculptures by Lloyd Lillie, were draped and veiled and shrouded by cobwebs, and black and orange ribbons twined through the railings leading upstairs.

There was something creepy about all of those bronze people ensnared by dusty webs, frozen mid-gesture, mid-conversation, skirts mid-sway. Except for the cobwebs, they looked so real that, if I hadn’t been wearing my glasses, I might have mistaken them for just a cluster of people in the lobby with plaited hair and sunbonnets and a stovepipe hat, baskets and reticules in hand, some leaning into a discussion, some gazing off into the distance at the same spectacle.

Meant to be Halloween-festive, the cobwebs made me think of something old and irrelevant, relegated to a dusty attic, a direct contrast to the movement implied in pleats and folds and scalloped sleeves and the curls of Frederick Douglass’s hair. Cobwebs: wafting strands of old spider silk that serve as magnets for dust, for hair and fibers and human skin cells and burnt meteorite particles.

Upstairs, past a life-sized terra cotta sculpture of Sojourner Truth, people swarmed, thirty or forty who quietly moved from one exhibit to the next: The Declaration of Sentiments, of which Stanton was the principal author, modeled after the Declaration of Independence and asking for voting rights and reforms in other laws; a Declaration of Equality for Muslim Woman written by representatives from the University of Buffalo School of Law in 2013. Around a corner, a young woman asked an older one what the election of Hillary Clinton would mean to her.

“A lot,” she said, swallowed hard, and walked away.

Heading next door to what remained of the Wesleyan Chapel, where 68 women and 32 men signed the Declaration of Sentiments, I passed the sculptures again, with their cobweb shawls and dusty streamers. Such strands woven by spiders function as homes, protection, sustenance, and travel aids, lines that allow them to jump or swing from one place to another like children on ziplines. I saw a nerve-wracking confidence in these fake cobwebs that mimicked spiders’ abandoned graveyards, or maybe hope, that we’d moved on, way past the need for these brave reformers, crocheted together in a weird solidarity.

I wandered through the Wesleyan Chapel, observing its brick and plaster walls, stone floor, wooden rafters, and long pews. Outside the window, a little girl walked by wearing a three-layer cake costume, headed home from the Halloween parade.

Upstairs in the museum I had just left, a display asked, “What does a surgeon look like? What does a president look like? What does an artist look like? What does a park ranger look like?” Under these questions, you could peer through windows and see mirrors, your own face. Outside the window of the Wesleyan Chapel, superheroes and princesses straggled by. A girl rode down the street on a rubber chicken.

Now, a month later, we are a few weeks past the election, and, it feels, ages past the hopes and expectations of that day. Costumes have no doubt been put away and cobwebs dusted off the bronze reformers. I imagine them polished and waiting, shining with new relevance as we wait to take the next step.