In Books We Trust: On Reading and Building Identities

In Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, the first book we see in the graphic memoir is right on the first page. The narrator’s father is reading Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. After that, books are almost always in the picture: most pages have a scene with books lying around or lining the shelves.

The discussion of the father’s homosexuality, as well as the narrator’s, also emerges through books. “My father’s death was a queer business,” Bechdel writes, “queer in every sense of that multivalent word.” The accompanying image is a dictionary opened at the entry “queer.” This is reprised a few pages later when Bechdel goes on to talk about her own “revelation,” one “not of the flesh, but of the mind”:

My realization at nineteen that I was a lesbian came about in a manner consistent with my bookish upbringing. (…) I’d been having qualms since I was thirteen when I first learned the word due to its alarming prominence in my dictionary. But now another book—a book about people who had completely cast aside their own qualms—elaborated on that definition.

One book leads to another, and soon Bechdel “was trolling even the public library,” in search of books that will lead her to learn and explore what being a lesbian can mean.

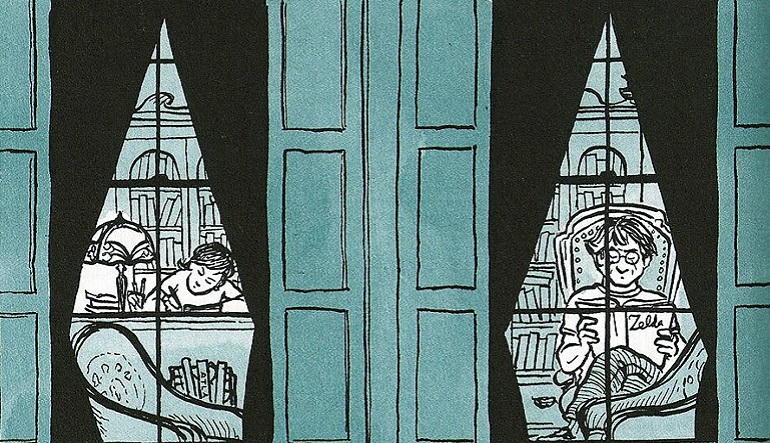

Parallel to that, her parents are depicted as readers. Her relationship to them is not just refracted through books: it needs the written word to make sense of it all. About halfway through Fun Home, we see father and daughter in the family library: seen from outside and each framed by a window, they look both isolated in their respective activity (he’s reading Nancy Milford’s Zelda, she’s filling in a check he’ll sign to pay for books she needs), and communing through this proximity.

As I read Fun Home, I immediately started relating to the narrator’s trajectory—over both her queerness and the way she relates to the world. I still remember the derisive reaction of many children and adults when, as a child, I explained how much I’d learned from books. After all, books are most decidedly not Real Life, a bit like the separation line that runs between what goes on online and IRL. Books can’t teach you to have Real Experiences. While you’re reading, life just zips by and you’re missing out on actually living. Of course, we also know that such distinctions are prone to blurring.

Bechdel’s memoirs highlight the obvious and absolute necessity of books to the learning and understanding process. Books aren’t the only thing that helps acquire experience but they’re a cornerstone of that process, especially when it comes to realizing a part of one’s identity that’s so often repressed or marginalized in social contexts. When I first understood that I was probably not entirely straight, my first instinct was to read about it—to look for stories and texts that depicted and discussed what it meant to be gay. No one around me, in my immediate circle of relatives and friends, would have been able to help me formulate what I was feeling; instead, reading the works of lesbian writers comforted me, provided me with a space that was entirely my own to come to terms, at my own pace, with who I wanted to be. So this is what I’d want to argue: books are a part of what everyone calls real life, and much of how we come to construct ourselves derives from what we read.

Nevertheless, and I feel it’s important to point this out, what with the slew of studies we’re inundated with nowadays, all singing the praises of reading, all explaining how science just proved that reading makes us smarter, less stressed, and more empathetic, all promoting reading as some kind of ultimate panacea—it’s important not to spiral into some kind of weird elitist book fetishism.

Pretending that books are the one potent cure-all for bigotry and ignorance often transforms reading into little more than performative allyship and shallow political sentiment, as Kevin Nguyen astutely points out: “The logic of Book Twitter is: Books are inherently good. Therefore, if we’d all just read more books, Donald Trump wouldn’t have been elected.” But, Nguyen goes on, “If you believe that books have the power to do good, you also have to believe that they can do just as much harm. After the election, there was no soul searching on Book Twitter.”

This isn’t to say that reading has no political impact. For those of us who have found ourselves marginalized and rejected at some point in our lives because of who we are, books can offer a refuge from which we may attain some understanding of ourselves and the world. Reading can encourage empathy and solidarity. But this means that reading remains, at its core, an active process: if you want to promote the idea that books and reality are not at odds with each other, you must actively integrate what you learn through reading into your life.

Bechdel first reads about lesbians, and then, later in college, decides to go to a meeting of “something called the ‘Gay Union.’” Her subsequent relationships are suffused with the written word: her lover’s bed “was strewn with books (…) in what was for me a novel fusion of word and deed.” Even the dictionary becomes erotic. Notice the process: as a reader, she carries this attention to the written word into her way of apprehending the world. Later, she brings back the world into her reading. Could that be what we should aspire to in our reading practice for the upcoming years? To be mindful readers, who read for escapism and for change, who seek to transform their consciousness and apply the lessons learned to their non-reading life? In short, to be people who can exist and nimbly move around within this continuum between books and the so-called real life?