Latinx Faculty at Writing Retreats

Novelist Cristina García and I were recently discussing the diversity of writing communities at summer retreats, and both came to a similar conclusion. There are many writing communities to choose from: some programs function on a model of accepting only participants and faculty of color and others stand by their missions of having an open participant pool while filling all faculty slots with people of color. The common factor among available options, however, is that writing retreats both new and long-established are devoid of Latinx faculty.

Finding Latinx faculty at summer retreats is virtually impossible. I was not surprised to read and hear about Jean Ho’s recent experience at Bread Loaf. Ho’s article on VIDA’s website “Report from the Field: Getting Along Shouldn’t Be an Ambition” should serve as a wake-up call for broader inclusivity and change in culture.

Latinx writers make up a significant population of the literary community and they make up the largest ethnic minority in the U.S. at 18% of the general population. Yet, literary institutions seem to find it difficult to be inclusive of Latinos as participants and as faculty. It is no surprise that many writing communities serving people of color have started their own writing institutions–Cave Canem, Kundiman, Macondo, CantoMundo, and VONA, to name few.

One writing program whose faculty list has always been composed of people of color is Las Dos Brujas Writers’ Workshops. It prides itself on having faculty of color as a draw for its applicants. García, who serves as the artistic director, theorizes that if you have faculty of color, “the writers of color will come without having to say this is just for writers of color. . . . I believe in inclusivity but I also thinks it’s crucial to have writers of color as workshop leaders in the classroom, as professors, looking for writers who are overlooked.”

During the workshop’s first conference, more than half of its participants were participants of color; the other participants were the minority. García noted that “participants who were not participants of color took an observational role, which is something that happens often when you’re marginalized—you’re relegated to being an observer. The sense of marginality and centrality is flipped on its head.” Often being put in an observational or marginalized role must occur to develop empathy for others.

Last year, a study published by two New York University professors titled “The Importance of Minority Teachers: Student Perceptions of Minority Versus White Teachers” was featured on NPR. The study attributed a preference for teachers of color to their ability “to draw on their own experiences to address issues of race and gender.” This preference is all too familiar to me. During my time in writing communities, I was fortunate to work Claudia Rankine, Jimmy Santiago Baca, Willie Perdomo, and Valerie Martinez—that’s four faculty of color at more than half a dozen writing communities I attended. There are scores of writing residencies that nurture different communities of writers, yet there are few writing communities that are specifically led by or inclusive of Latinx faculty.

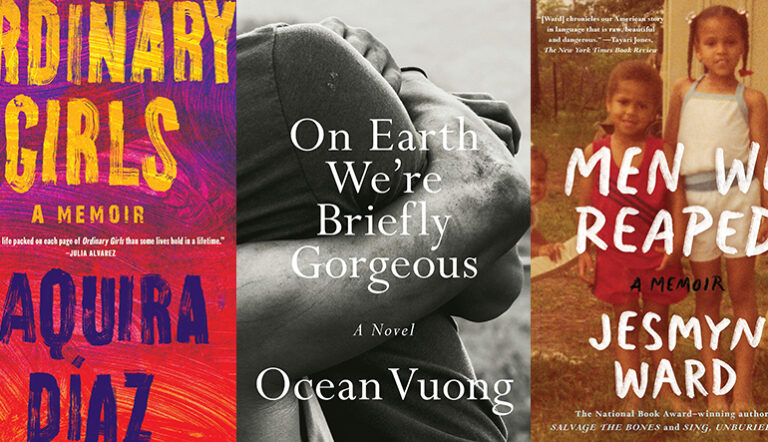

CantoMundo, Las Dos Brujas, and Macondo have gained prominence in the Latinx literary community as networks for nurturing new and emerging writers. The growing number of Latinx writers in the U.S. has created a need for community infrastructure to foster new and emerging voices. It is unimaginable that there are only a handful of faculty of color to lead workshops at writing institutions, but that’s a fact when searching for Latinx faculty in the oldest and long-established writing programs–and this must change.

My conversation with García led me to ask other Latinx writers to share their experiences with writing communities, either as a participant or as a faculty of color. Their responses are below.

“Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference, which I first attended 1969, used to be a white-bread slice of American letters at the time, not many writers of color as staff or contributors. Under the directorship of Michael Collier, this predominately white and male demographic has changed. I think it deserves mention. A real magic mountain of a place. Recently, I just wrote about Judith Ortiz Cofer, wonderful writer, who was my only hermana in letters at BLWC back then. It speaks to how far the place has come.

Helena Maria Viramontes at Cornell has nurtured a great number of amazing young writers in the program there, writers who have gone on to be our current literary stars, including Junot Diaz, Manuel Muñoz, H. G. Carrillo, Brian Leung, J Rattawut Lapcharoensap, Jennine Capo Crucet, Mario Zamora, Reyna Grande, Catherine Chung, NoViolet Bulawayo, George McCormick.”

“The winter quarter of my first year of grad school, I saw an advertisement for a workshop specifically aimed at writers of color. The ad mentioned the words community and activism, nurturing, and critical. These people will get me, I thought. Yeah, they’re gonna be tough. But they’ll be nurturing. Because we’re community. We’re brothers and sisters. Says so right there in the call for participants. The reception I got was the equivalent of a public thrashing. Not just from the facilitator, a brother of color, but from the entire group. I sat there quietly as they hurled insults at my writing and at me. It was nonstop. A fucking flogging. Where was the love? And, of all the participants in our group that week, I was the only one who received that treatment. Growing up with a disability in my neighborhood was tough, and I was used to being picked on and pushed down. After that incident, I did what my brothers taught me to do: I got up off the floor, dusted myself off, and continued. My community was out there, I told myself. They’ll find me.

Macondo found me at a moment of crisis, when I was looking for a place to share my work in an environment that was both nurturing and critical. My workshop community there was mindful of what I was attempting to do, and they had the good sense and skill to dole out tough criticism and support simultaneously, a technique—I’ve come to realize—that is a lot harder to do than one thinks. With Macondo, I realized that a space for writers of color could be both nurturing and critical and that it was up to me as a teacher of the craft of writing to be mindful of the past assaults my students bring to the table yet brave enough to be honest with them. When done right, spaces like Macondo, spaces for writers of color, can serve as opportunities to enlighten and strengthen our artists and not beat them down for no apparent reason. When done badly, when there is ego involved, these spaces do more harm than good. As teachers of color in these spaces, we should be expected to tread a little more lightly and to acknowledge our positions of privilege. Otherwise we are no different than the systems of oppression we are fighting so hard to get our students to recognize and change.”

“One of the reasons I love teaching at residency programs—Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center, New Harmony Writers Workshop, Napa Valley Writers Conference, and Writing by Writers, to name a few—is that I often get an opportunity to work with a diverse group of writers. My workshops are a mix of returning writers who have spent years doing something else, and young writers who have full-time jobs and are trying their best to carve out a creative life as well as make a living. Depending on the residency, there’s also a good mix of students of color. This mix of different perspectives allows for the workshop and the residency to become something of sacred space, where it’s not about credit or coursework, but about dedicating yourself to what you value.

For students of color, these residencies can often serve as a space to build community in a way that some more traditional brick and mortar programs don’t. Let’s face it, when your undergraduate program or MFA program has only one other student of color in the workshop, it can be frustrating, alienating, and it can be remarkably hard to feel seen. Alternatively, when residences offer an opportunity for students of color to come together, along with faculty of color, there’s a freedom of thought and movement that feels almost thrilling. When the conversation flows more freely and the opportunity for connection feels authentic, there’s a level of openness attained in the work and in the room.

As a writer/teacher of color, residencies allow me to provide support to students who may or may not have had an advocate in another program. Faculty of color do more than just model for students, we also often serve as sounding boards and emotional support systems. It’s incredibly important for all of us to be able to envision a life as an artist, especially when things seem so hard right now. Residencies that focus on hiring faculty of color are letting everyone envision that type of artistic future.”

Florencia Milito

“As an immigrant who was born in Argentina and spent part of her childhood in Venezuela, whose family fled a brutal, U.S.-supported military dictatorship, my sense of identity with respect to my place in this society has always been complicated. A sense of dislocation, of alienation, of rootlessness has fed my impulse to write, has made poetry home from a young age. It has also led to paralyzing silences. CantoMundo, perhaps more than any other writing space I have inhabited, felt very much like a homecoming: a space that doesn’t draw false dichotomies, that honors both the political and psychological, a place where my uprooted self could find something of a refuge, where my Spanish and English selves could coexist. What’s more, it struck me as brimming with purpose, brilliance, warmth, and hermandad.

I’m in my early forties, the mother of two young children. My days are mostly not my own. Nothing like CantoMundo existed when I was in my twenties. I have no doubt that if I had found the kind of crucial mirroring it offers earlier, my productive writing periods would have been longer, my silences shorter. We find ourselves in surreal, unchartered territory, as if a cosmic glitch had occurred and trapped us in a grotesque, unintended timeline. Given what lies ahead, and the courage that will be required of us both as people and as writers, finding this community at this historical moment feels like nothing less than a lifeline.”