“Why Doctors Make Natural Writers”

A patient, long before he becomes the subject of medical scrutiny, is, at first, simply a storyteller, a narrator of suffering…”

—Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Emperor of All Maladies

Doctors have been writers for as long as they have been doctors. From the time of Galen, ancient Greek surgeon and philosopher, to Avicenna in the Middle Ages, through the great Enlightenment thinkers, virtually any scientist would have considered himself an equal champion of the narrative arts. The disciplinary divide between the humanities and sciences is a recent invention. Galen even wrote a treatise called An Exhortation to Study the Arts, directing physicians to develop a broad intellect, as well as a short book, The Best Physician is also a Philosopher.

Judging by the quantity and quality of writing by doctors in the past several decades alone, I might also suggest that some of our best philosophers have been physicians. The list of doctors-turned-writers is long and ever-growing: Abraham Verghese, Viktor Frankl, Oliver Sacks, Irvin Yalom, etc. There is also a robust lineage of doctors who became primarily writers, as opposed to doctors who took up writing as a secondary avocation: Walker Percy, William Carlos Williams, Somerset Maugham, Anton Chekhov, and more. Some have viewed and even helped define the zeitgeist through the lens of disease, like Siddhartha Mukherjee, who pioneered a cultural-historical approach to writing about cancer. Others have accessed philosophy through the exploration of foundational questions about medical ethics, practice, and mortality, like Atul Gawande. In Being Mortal, his 2014 study of how and when we die, Gawande writes: “We’ve been wrong about what our job is in medicine. We think our job is to ensure health and survival. But really it is larger than that. It is to enable well-being. And well-being is about the reasons one wishes to be alive.”

Gawande understands that the practice of medicine necessitates a confrontation with essential things; with the base material and emotional circumstances of our lives. When patients come to their doctors with cancer, mysterious pains, even the common cold, they are asking not only for treatment of their ailment, but for a return to conditions in which they may thrive. These conditions vary from patient to patient—it is thus the responsibility of the healthcare provider to suss out the dominant narratives the patient has told themself about who they are and what they value.

Doctors must listen to and participate in patients’ stories about their lives in order to determine what matters to them, and what, therefore, is worth preserving, what is worth fighting for. If the patient sees himself as the protagonist in a tale of athletic achievement, then he will want to choose surgery to repair a torn knee ligament, not merely physical therapy, so that he can live to play another day. But if the patient, an accountant, fears the potential complications and after-effects of going under the knife, then it may make more sense for him to rehab the leg. There are few objectively correct standards of treatment, it turns out: only what works for whom at what time.

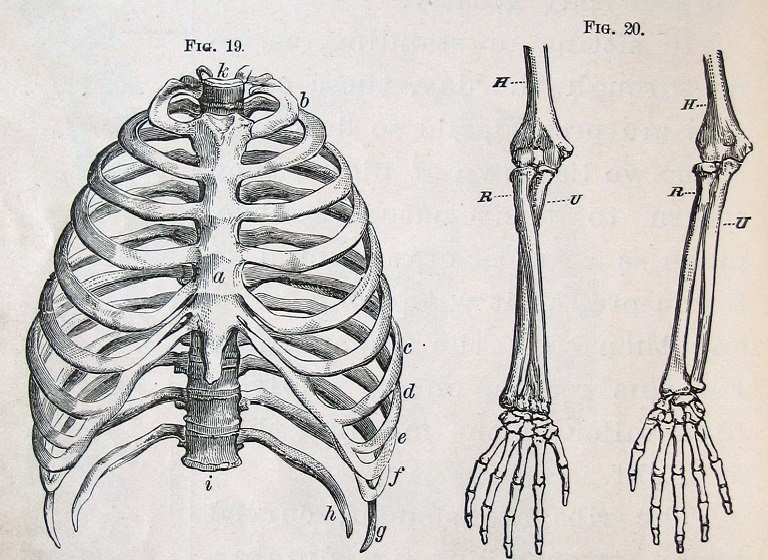

This situation represents a relatively low-stakes example of how self-told narratives can (and should) direct treatment. Some physicians have written about more urgent instances. Paul Kalanithi’s bestselling memoir, When Breath Becomes Air, tracks the author’s journey through college, medical training, and finally a neurosurgery residency, in the last year of which he is diagnosed with Stage IV lung cancer. With an indeterminate (but probably truncated) amount of time left to him, Kalanithi finishes his residency, writes his memoir, and has a child with his wife Lucy, also a physician. Paul and Lucy agree that value in life comes not from avoiding pain, but from creating meaning; their decision to become pregnant at such a difficult time bears out this belief.

Kalanithi spends much of the rest of the book detailing his upbringing and the intellectual path that led him to medicine. It is telling that, before deciding upon medical school, he wanted to become a writer, to explore the fundamental truths that underlie human behavior and relationships. Ultimately he chooses to pursue this goal through surgical practice, but the reader senses that he could have gone either way. I suspect that some of the same character traits draw people to both professions: a curiosity about human nature; an interest in cause and effect; a profound desire for connection through the perfection of a craft.

In his surgery career, Kalanithi finds a richness in “reading” the stories of his patients’ lives, in learning who they are outside the hospital: whom they hope to return to being. When he cuts into a patient’s brain, he thinks of her family, her hobbies, her aspirations. Recalling these personal details reminds him of how much is at stake under his hands, and why the practice of medicine is not merely a craft, but truly a calling:

Don’t think I ever spent a minute of any day wondering why I did this work, or whether it was worth it. The call to protect life—and not merely life but another’s identity; it is perhaps not too much to say another’s soul—was obvious in its sacredness. Before operating on a patient’s brain, I realized, I must first understand his mind: his identity, his values, what makes his life worth living, and what devastation makes it reasonable to let that life end. The cost of my dedication to succeed was high, and the ineluctable failures brought me nearly unbearable guilt. Those burdens are what make medicine holy and wholly impossible: in taking up another’s cross, one must sometimes get crushed by the weight.

For Kalanithi, and for great doctors generally, there is no greater privilege than that of taking on another man’s weight, at least while he remains in their care. After all, to intervene so dramatically in another person’s story is to assume a great burden of responsibility. No wonder our healers find themselves moved to share the adventures in humanity that constitute their everyday lives—to bring the rest of us into a realm that can be, above all, terribly lonely.