Stories Strangely Told: Borges, Bad Art, and the Infinite Aleph

Stories Strangely Told is a monthly series that explores formal experiment in short-form fiction.

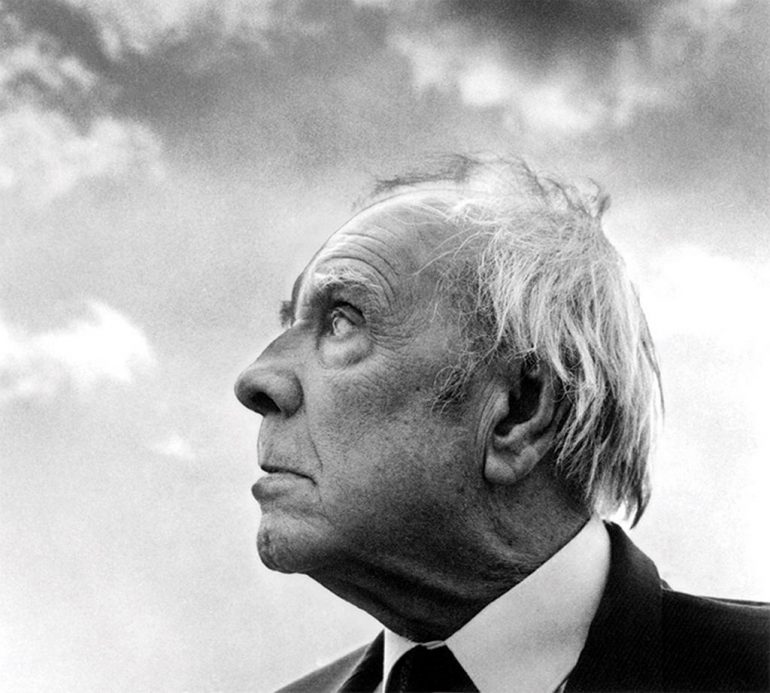

“The Aleph” by Jorge Luis Borges concerns, along with mirrors and the infinite: the demolition of a house, literary prizes, fragile egos, café lighting, the death of Beatriz Viterbo (the object of the narrator’s veiled love), and a few terrible stanzas by Carlos Argentino Daneri, a pompous and longwinded academic who has taken it upon himself to write a poem whose theme is the entirety of Earth. Carlos Argentino is a vivid presence: “a pink, substantial, gray-haired man of refined features” who works at a library on the outskirts of Buenos Aires. At two generations’ remove, “the Italian s and the liberal Italian gesticulation still survive him.” He is the sort of man who is given brandy and pronounces it “interesting.” The sort of man who, like a more self-involved copy of Mrs. Dalloway‘s Sir William Bradshaw, utters his reliance on the “twin staffs Work and Solitude.” He is a man, in short, who is insufferable. When the narrator of “The Aleph” asks him to read from his poem, he snatches quick at the opportunity:

I have seen, as did the Greek, man’s cities and his fame,

The works, the days of various light, the hunger;

I prettify no fact, I falsify no name,

For the voyage I narrate is . . . autour de ma chamber.

Gauzy abstractions, self-conscious French, the empty signification of “man’s cities and his fame,” and the total malarky of “days of various light,” which sounds kind of cool even in the original Spanish (los días de varia luz), until you realize the meaning is that some days light looks different. Daneri calls this his “Prologue-Canto,” the first in an “ambitious series.” And the name is perhaps unintentionally astute, for the poem seems dredged from the swamps of Pound’s own Cantos—minus the occasional crisp image, the playful torque of language, but saturated with that same self-amused grandiosity, those burdensome allusions that ring more of sleazy showmanship than a desire to reach out and touch a reader’s hand.

I find myself needing to step back here, poking at the flaws of a poem that does not truly exist, written by a man who is an illusion of a few well-measured sentences. Perhaps there’s something particularly absorbing in Borges’s experiment, which delights in bending fiction into essay—so that “The Aleph,” with its sweep of detail and steady action, seems to announce itself from the gate as fiction, but on its way startles with the admission that its narrator is a writer, also named Borges, whose book, The Sharper’s Cards (an actual early book of the real writer Borges), loses a fake literary prize to Daneri’s fictional canto. It’s a rare art that holds up its very artifice and at the same time entangles you in its web.

Of course Daneri disagrees with my assessment. “A stanza interesting from every point of view,” he tells Borges of his own poem. In the self-congratulatory monologue that follows, he describes the poem’s “dazzling new edifice,” its range of allusions to “thirty centuries of dense literature,” its unusual rhyme and its definitive impression on the learned, save the “would-be scholars that make up such a substantial portion of popular opinion.”

After hearing a few more stanzas (“all of which earned the same profuse praise”), Borges is able to diagnose the problem: “that the poet’s work had lain not in the poetry but in the invention of reasons for accounting the poetry admirable.” Naturally, he writes, “that later work modified the poem for Daneri, but not for anyone else.” It’s an interesting position. Borges, who kept whole libraries in his mind, couldn’t seem to write a single story of his own without folding in a dozen fables and novels and encyclopedias he’d read through. The fact is that Daneri’s self-professed allusions—from Homer to Hesiod to pastoral elegy to the playwright Carlo Goldoni and so on—mirror Borges’s own stories, which, as David Foster Wallace puts it, “make stories out of stories,” collapsing “reader and writer into a new kind of aesthetic agent.”

So for all the grotesquery of Daneri, is there something admirable in his obnoxiousness? After all, he wants to capture, well, everything in his poem, the whole planet. Even if his method is wrong, is there something devotional, something compelling and even admirable in his attempt? About two-thirds of the way through the story, we learn that Daneri has been granted the greatest gift imaginable: the infinite, all-seeing eye of God. “The Aleph,” he tells the narrator Borges, “is one of the points in space that contain all points.” It’s where, “without admixture or confusion, all the places of the world, seen from every angle, coexist.” Daneri says he discovered the Aleph in his childhood cellar; he says that it’s still there. It’s his muse, his inspiration. Or it is the vehicle that allows him to see his muse: the simultaneous coexistence of all things.

If at first you don’t believe Daneri, neither does Borges. Hanging up the phone, he reflects that sometimes “learning a fact is enough to make an entire series of corroborating details, previously unrecognized, fall into place; I was amazed that I hadn’t realized until that moment that Carlos Argentino was a madman.”

But the Borges narrator does visit. He allows himself to get locked in Daneri’s cellar. And there what he sees is worth the imposition of a lengthy quote. Under the step, toward the right, writes Borges:

“I saw a small iridescent sphere of almost unbearable brightness […] I saw the populous sea, saw dawn and dusk, saw the multitudes of the Americas, saw a silvery spiderweb at the center of a black pyramid, saw a broken labyrinth (it was London), saw endless eyes, all very close, studying themselves in me as though in a mirror, saw all mirrors on the planet (and none of them reflecting me), saw in a rear courtyard on Calle Soler the same tiles I’d seen twenty years before in the entryway of a house in Fray Bentos, saw clusters of grapes, snow, veins of metal, water vapor, saw convex equatorial deserts and their every grain of sand, saw a woman in Inverness whom I shall never forget, saw her violent hair, her haughty body, saw a cancer in her breast, saw a circle of dry soil within a sidewalk where there had once been a tree . . . “

And though this rush of detail continues on significantly longer, I hope at least this introduction to the narrator’s vision expresses just how beautiful and overwhelming the Aleph actually is—a fact worth chewing on because what we now have are two simulacra of infinity: one beautiful, one grotesque.

Daneri’s poem of infinite allusions, which exist for his mind alone, is of course solipsism; it’s the infinite bent inward. For to draw obsessively into our minds, into the echo chamber of our art, is to draw away from others, from the possibility of connection. And while it would be easy to say here that Borges’s vivid details—the spiderweb in the pyramid, the snow, the veins of metal—do reach out and communicate, Borges himself points out that what he wants to share is still veiled in the inexpressible.

“In that unbounded moment,” he writes, “I saw millions of delightful and horrible acts; none amazed me so much as the fact that all occupied the same point, without superposition and without transparency. What my eyes saw was simultaneous; what I shall write is successive, because language is successive.”

Two expressions of the infinite. Two forms of experiment. Has the more beautiful prose actually succeeded? Or is there an honesty and value to Daneri’s poem, which fails to capture the Aleph? What of the inexpressible can be expressed?