Confronting Our Environmental Apocalypse: Climate Change, a Secular Christian Story

The posts in this series, Confronting Our Environmental Apocalypse, consider various traditions, ideas, and/or authors in the search for imaginative ways to give voice to our current ecological disaster.

Attending a Catholic middle school and high school, I was nonetheless raised to think for myself and question everything. I did this furiously and with no small amount of delight. As with most thoughtful teenagers, I made good use of the term “hypocrite,” especially when it came to the wild disconnect between the established Church and the teachings of Jesus. No doubt an easy target, but one I got particularly fired up over. I was young, naïve, and had not yet fully grasped just how universal it was for people and institutions to miserably fail to catch up to the ideals they expound.

Jesus asked a lot from his followers, probably more than anyone can live up to. Perhaps humanity is too wretched, or perhaps Jesus simply expounded a doctrine that grew out of idealism, not experience. His radical, utopian vision, where violence is eliminated from human relationships, where love undermines legal institutions and traditions, may be beautiful, but to truly believe that loving one’s enemies and giving one’s life over to faith and charity would bring about a world where the last would be first, and the empires and powers of the earth would crumble, displays little understanding about humans or the world.

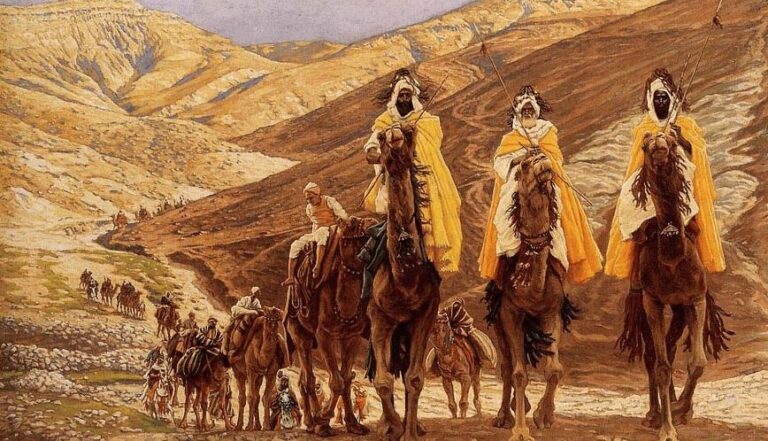

The grounds for such a radical moral vision was not that Jesus simply tapped into people’s desire to live a better life or make the world a better place, surely, a big component was the apocalyptic foundation of these teachings. The prospect that the world they knew would soon come to an end made such impossible precepts catch hold among his early followers. “The news of the approaching end of the world and an appeal to all to prepare themselves immediately for the final cataclysm,” wrote the 20th century Polish philosopher, Leszek Kołakowski. “The expectation of imminent catastrophe imposed an entirely new perspective on things.”

From the shadow of the apocalypse emerged wider possibilities to reimagine human relationships, a new way of being in the world, one many billions would accept, even if the could never catch up to this vision.

_______________

Much of the discussion around climate change and the environmental catastrophe we’re living through contains echoes of the Christian story. Carbon-based energy sources, over-consumption, and capitalism’s relentless drive for growth and profit have replaced sin and wickedness. If the nations of the earth continue in this way, cataclysmic catastrophes surely await. We are now at a point of reckoning when drastic changes need to take place, and as Jesus was the way through which the sinful world could be saved, for us, it is the right policies and by developing the right technology, that a cleaner, healthier world—i.e.: the kingdom of heaven—will emerge.

What is so interesting about the parallels between climate change and the Christian tradition is that the prospect of an unimaginable calamity allows the imagination to flourish. This is evident in Jesus’ teachings, in the works of Paul, and the fusion of Greek and Jewish thought over the next few centuries, in a time when God’s judgment and the end of the world was just as real to the believers as the rising oceans, methane emissions, atmospheric imbalance, and acidification of the ocean are to the secular mind.

Is there a story of redemption in how we deal with this ecological apocalypse that seems to be upon us? If the Day of Judgment and the coming apocalypse was the impending horror that brought forth the freedom to radically rethink human relationships and our being on Earth, is something similar now happening, though on a secular level?

There is a superficial resolve that says we must change our spending habits and buy different light bulbs, hybrid cars, energy efficient appliances, and support climate-conscious policies. There are more radical groups like the freegans who are daring in their calls to change how we live, and those like myself, who believe any truly effective solution to climate change will demand a radical transformation of who we are as people, a change from homo economicus to a manner of being that is wholly different than most live, or aspire to live, in the 21st century.

Saint Paul said the followers of Christ must be reborn in his spirit; to fully respond to the environmental disaster upon us, do we, as a species, need to be transformed into something more than consumers?

The history of Christianity is the history of people throwing themselves before their faith, professing to follow Jesus, praying, producing no end of doctrines and encyclicals, and while doing so, utterly failing to follow in their founder’s footsteps.

Likewise—and I may be accused of being cynical here—even for those who are aware of climate change and its devastating effects, the need to change how they live, how we all live, is primarily manifested in different shopping choices and vilifying big fossil fuel and the Koch brothers, (who, don’t get me wrong, are definitely villains). Despite the professions of faith and desire to curb the ecological ruin, most are still complacent participants in the system that produces the effects they wish to fight against.

This is not because most are hypocrites or apathetic, but because we are too tied into the ways of the world, to the economic system and mode of life by which we exist, and which contribute to climate change.

Living in the end times or facing a calamity of any variety may generate an abundance of imagination, but alas, a lack of action. This chasm between our ideals and the reality in which we live has always been fertile ground for artists. In the current ecological crisis, the inability to respond, to act on an individual level, points to something deeper than hypocrisy. It points to both a human strength (the ability to imagine) and those great, all too human flaws, namely, that so many of us live contrary to our beliefs and desires.