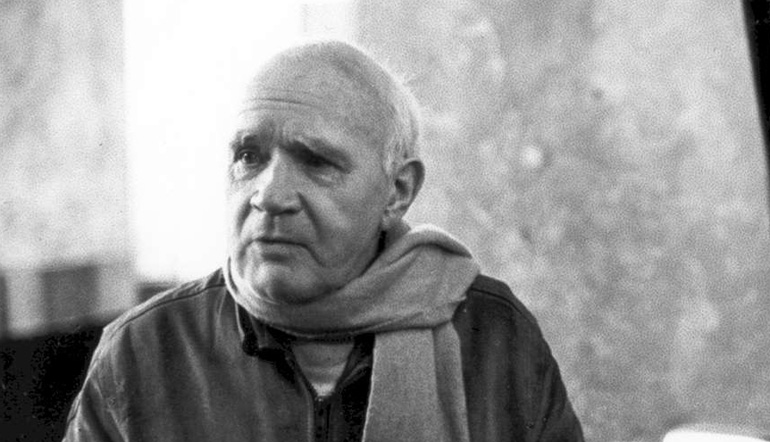

Jean Genet’s Bodies & Borders

In 1941, in Paris’s Prison de la Santé, Jean Genet was given three days’ solitary confinement for writing. On sheets of paper he’d been given to make into bags, Genet had begun his first novel: Our Lady of the Flowers. The prison guards would burn this first draft, and so he later transcribed it from memory—apparently almost word for word.

This act of material subversion, this image of writing so implicitly underpinned by pragmatic defiance, has garnered much romantic attachment since 1941. Nonetheless, it resonates with the mutual dependence of literature and bodily circumstance. With Our Lady, born into the world on paperly contraband, the two are formally and thematically linked: the novel’s very substance is the masturbatory fantasies dreamed up in the company of prisoners, and the prose reverberate with Genet’s arousal and confinement. As Max Nelson writes in the Paris Review:

The shape of the novel’s convoluted, embellished sentences seems wedded precisely to the purpose they might serve in the imaginative construction of a prisoner pleasuring himself under the cover of darkness. They stall extravagantly, delaying climax . . .

This kind of writing, one generated directly from embodiment and encounter, would persevere throughout Genet’s oeuvre. Not only would his marginalized position forever be entrenched in his work, but his writing through a sense of displacement would paradoxically result in a stark and sensual corporeality: Genet wrote an ideology and phenomenology of the outcast into being.

Much has been made of his early life. Abandoned by his mother at seven months old, he was raised in state institutions and charged with his first crime when he was ten. He went on to spend most of his adolescence in a reformatory before enrolling in the Foreign Legion, which he deserted before turning to theft and prostitution. After repeated jail terms he was sentenced to life imprisonment, but Jean Cocteau, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Simone de Beauvoir lobbied for his release and secured him a presidential pardon in 1948. (Contemporary fans include David Bowie, Primal Scream’s Bobby Gillespie, and Patti Smith.) Now heralded as a genius, Genet nonetheless continued to lean on his status as an outcast and privilege the insights it yielded. Writing from society’s outskirts, he set about eviscerating phallocentric norms and performing the “transvaluation of values” for which he is now so well-known: in Genet’s work, betrayal and murder are kinds of devotion, theft and imprisonment, the means by which his characters achieve heroism and freedom.

I fear nothing. Morality clings to me only by a thread.

In this upturned border-territory, then, Genet’s prose enacted a rigorous inquiry: how did his “outcasted” body move through the world? What were its sensations, its confusions and textures? Indeed, so infused are his diverse works with his subjective experience, taken together they form a syncretic autobiography—the real subject, as Steven Marcus notes, “is always the Genet who develops in the process of writing this book.”

This marginalized outlook and the deep embodiment it provoked later imbued his historical and political themes: Funeral Rites (perhaps the most contentious of his works) depicts tenderness, lust, and baroque sex among Nazis during WWII, and Prisoner of Love is a sensuous recollection of the time Genet spent in refugee camps in Palestine, as well as his involvement with the Black Panthers. Genet’s central inquiry remains evident in each: what are the means by which a person or people becomes “othered,” and how can heteronormative narratives be dismantled to depict them?

Whether problematizing our relationship to bodies we deem “evil” or “terrorist” by reading them in fantastical, tender, sensual terms or lyrically canonizing murderers, Genet’s writing from this “othered” place allowed for “self-examination, self-justification,” and, most importantly, “self-creation.” By inverting ideals and upturning the values on which orderly life hinges, Genet birthed a belief system in which the marginalized body holds sway and shapes the world around itself, and sees the textures of daily living altered accordingly.

A margin—a border—after all, insinuates a certain intensity: here, we might possibly become something else. Here, our defining properties are called into question. Genet’s work reminds us that the identities we ascribe to others are tenuously placed, but this assertion of porous personhood—though partly admonishment—is also hugely liberating. What his work leaves us with is a determined individualism: there is no body so one-dimensional that it falls prey to easy categorization, and we should resist the notion that any term—no matter how contemporary or radical—captures the breadth of a given subject, of any given “I.”