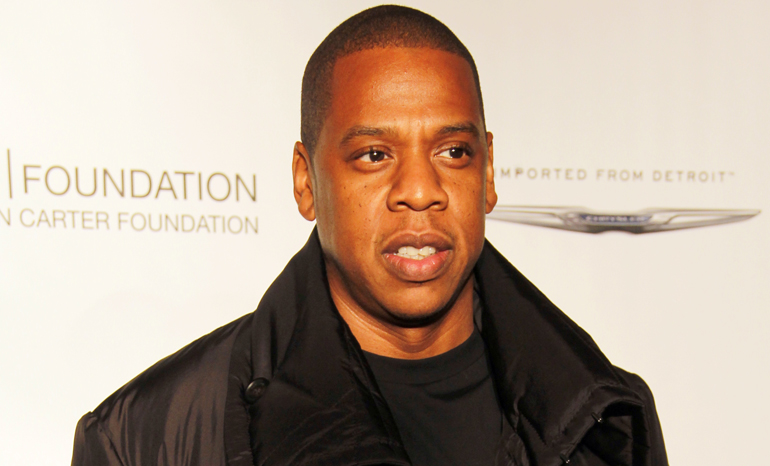

The Black Aesthetic: Money Talks in Jay-Z’s 4.44

In times of social turmoil, African American poets disseminate messages demanding change. Great writers such as Amiri Baraka and Nikki Giovanni wrote of freedom and the rhetoric of the Black Aesthetic. When poetry is set to music, harmonious beats relay liberating feelings that transcend history and culture. The Black Aesthetic is often universally pleasing, but beneath the verses documenting aspiration, empowerment, and fear is a call for cultural revolution. Read other posts for this series.

Jay-Z’s latest album 4.44 rejects racial transcendence, while promoting Black business ingenuity. With songs such as “The Story of O.J.,” Jay-Z disavows the belief that mainstream success transcends blackness. When Jay-Z says, “O.J. like, ‘I’m not black, I’m O.J.’ . . . okay,” Jay-Z dismisses rich and famous celebrities who deny their Black heritage. And, in “Caught Their Eyes,” Jay-Z references Prince’s desire for self-autonomy, while fighting for ownership of his own masters. Although Jay-Z’s 4.44 acknowledges America’s capitalistic history of enslavement and the tragic stories associated with Black celebrity, he promotes Black ownership as the dominant means for authentic financial freedom in America.

Light nigga, dark nigga, faux nigga, real nigga

Rich nigga, poor nigga, field nigga

Still nigga, still nigga

O.J. like “I’m not black, I’m O.J.” . . . okay

In “The Story of O.J.,” when Jay-Z says, “Light nigga, dark nigga,” he’s reminding Black folks, don’t get ahead of yourself. Regardless of your skin tone, in America, your Black skin defines how people see and treat you. To further reiterate the unification of Black identity, he speaks to every Black person, regardless of his or her economic status, as a “poor nigga, field nigga.” Jay-Z repetitiously raps the word “nigga” as a means of connecting Blacks of every economic classification. Then, by quoting a line, “I’m not black,” reportedly spoken by O.J. in The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and featured in the Oscar-winning documentary, O.J: Made in America, Jay-Z’s sarcastic response is “okay.”

Despite O.J.’s best efforts to pander to white society, O.J.’s talent didn’t grant him superhuman status or allow him to move beyond his own blackness. O.J. didn’t own himself or control his good guy image, which was manufactured for the benefit of entertaining whites on and off the football field via product endorsements. And, not only did O.J. fail to transcend race with his running back success, but he had no sense of personal identity beyond the cheers he received on the field and the white approval he ravished and craved. To Jay-Z, O.J. was a “field nigga” who played himself, since he was unaware that he was the property of America’s favorite pastime, football, and the men who owned this brutalizing game.

By alluding to the rise and fall of O.J., Black ownership of image, self, and property is a running theme in 4.44. Nevertheless, due to the slavery roots of American capitalism, African Americans have a complicated relationship with ownership. But, Jay-Z’s socially conscious album, 4.44, refuses to sidestep the complexity of America’s wealth and the systems and institutions that built it. With his video, “The Story of O.J.,” a cartoonish image with dark skin, large eyes, pronounced lips, and white gloves appears. His name is Jaybo, which is an allusion to a caricature of blackness, Sambo, found in lyrics, folk sayings, and literature. Ironically, Jaybo raps Jay-Z’s lines, in an attempt to reappropriate this exploited archetype of the lazy but happy Black slave, which was historically promoted by pro-slavery apologists in American culture.

With Jay-Z’s song “Caught Their Eyes,” the master-slave theme emerges again when Jay-Z references Prince. In 1992, after a fight with Warner Bros. music over the release of his song “My Name Is Prince,” he wrote the word “slave” in black across his cheek. As a result of the bitter feud, he refused to use the stage name Prince again until 2000. He once spoke to Rolling Stone about his fight for emancipation: “I don’t own Prince’s music. If you don’t own your masters, your master owns you.”

This guy had ‘Slave’ on his face

You think he wanted the masters with his masters?

You greedy bastards sold tickets to walk through his house

I’m surprised you ain’t auction off the casket

In those lyrics, there’s a sense that Black folks are betraying Prince’s legacy, by selling out Prince for their own self-profit. Jay-Z raps, “These industry niggas, they always been fishy.” They’re about the money because they’re withholding from Prince, in death, what he sought in life, financial freedom. When Jay-Z says the word “masters,” this pun has a dual meaning. The word “masters” refers to the copyright obtained by those who own a musician’s music. And, for musicians who don’t own the copyright to their music, they’re bound to unconscionable contracts that benefit the owners way more than themselves, the creators. Yet, when musicians seek to own their own intellectual property, the right to their music, it’s a fight orchestrated by music companies, reminding artists that they woefully don’t own their name, image, or music.

But, to Jay-Z who is worth $810 million, according to Forbes, Blacks must engage in the painful process of ownership. To have an authentic stake in this country, even if you’re rich or famous, if you don’t own yourself, like Prince says, figuratively speaking, you’re nothing more than a slave. Building more wealth for the men who own your name, your image, your Black ingenuity, is modern-day exploitation. In other words, if you’re not in legal possession of everything you’ve created and acquired, building wealth to pass on to the next generation won’t occur, because you own nothing.

Jay-Z shares the cautionary tales of O.J. and Prince to advocate for Black ownership. Both men were celebrity archetypes of Black success stories. However, O.J.’s name is tarred by the shame of his double murder trial and subsequent acquittal. Eventually, his tragic fall from White grace cost him everything. Meanwhile, Prince died with a $200 million dollar estate and no will. Yet, after a judge awarded Prince’s estate to his brothers and sisters, the fight to pillage his intellectual property from his rightful heirs continues. Even though both men represented Black success and possibilities, neither celebrity achieved “safe passage through white spaces, mouths and memories,” because racial transcendence is an American fallacy. Jay-Z reminds us that Black ownership of name, image, brand, and property is the only way to achieve financial freedom. Yet, due to our slave history, Jay-Z’s message is clear; even with economic freedom, we should never desire to escape our blackness, because we should never desire to escape ourselves even for supposed racial transcendence in America.