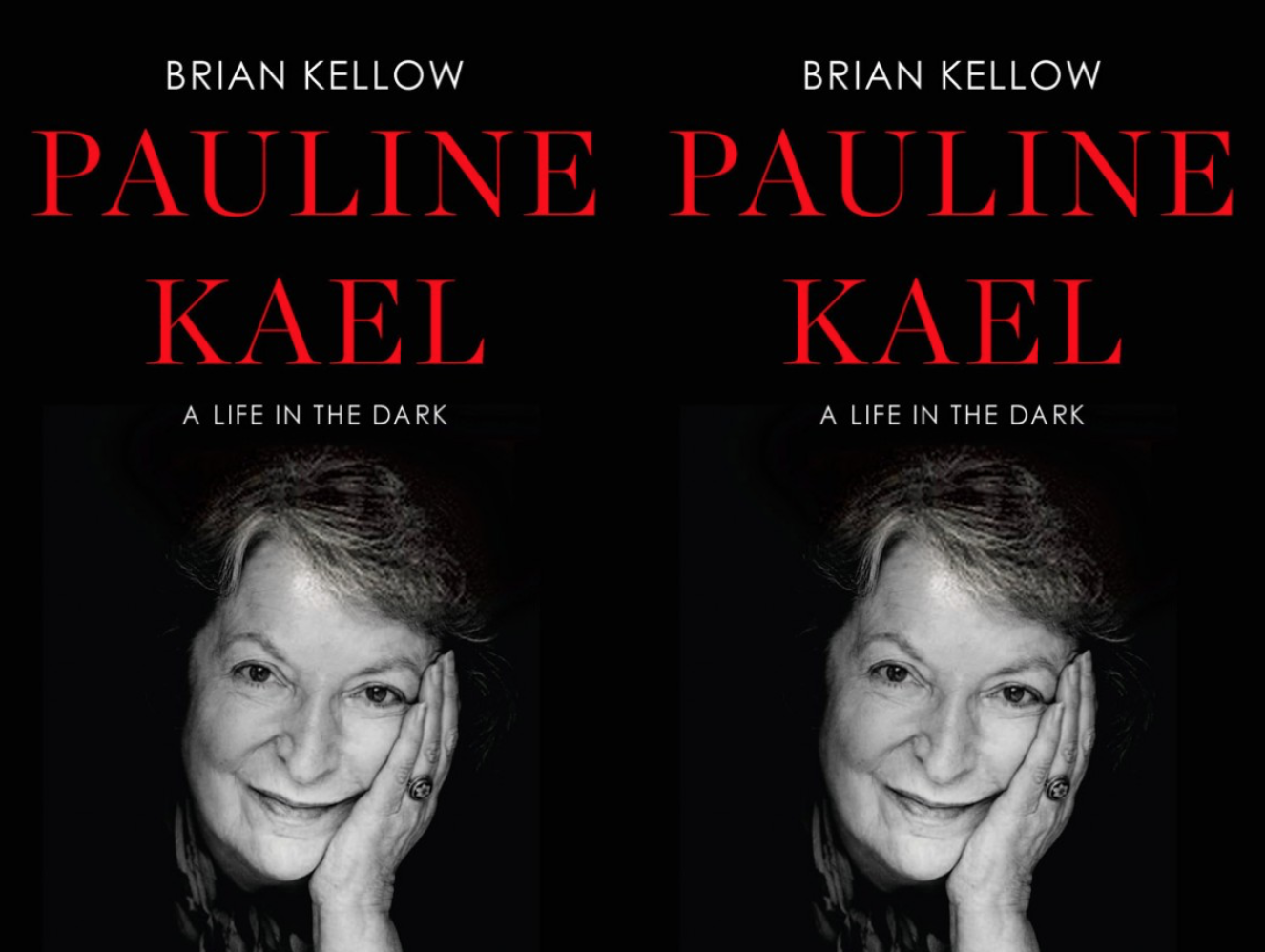

Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark

Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark

Brian Kellow

Viking Adult, October 2011

432 pages

$27.95

Please note: Emily Murphy is not the author of this post, contrary to what it says. The author is Joshua Garstka. See the bottom of the post for bio information.

“This was the world teachers used to pretend (and maybe still pretend?) was the real world,” Pauline Kael wrote about The Sound of Music in 1965. “It’s the big lie, the sugarcoated lie that people seem to want to eat.” Thanks to this scathing review, and others like it, Kael was ousted from her critic’s post at McCall’s, but soon her impassioned opinions landed her a spot at The New Yorker—and from there, she began a relationship with movies more sensual than with any lover. Movies were the real world, for Kael, and they deserved real criticism.

Brian Kellow’s biography Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark wisely charts Kael’s life by focusing on her writing. There are few personal stories here (mostly about her domineering control over her daughter), but this isn’t much of a disadvantage; the movies were enough for Kael, and her columns were a breathless look at the senses these movies evoked for her. Out with film theory and self-important pictures, in with well-made B-movies. Kael on Planet of the Apes (1968): “one of the best science-fiction fantasies ever to come out of Hollywood. That doesn’t mean it’s art.” On Robert Altman’s war satire M*A*S*H (1970): “I’ve rarely heard four-letter words used so exquisitely well.” Why sit through humorless Ingmar Bergman when you could kick back to Funny Girl?

Kellow thankfully doesn’t ignore the controversy Kael incurred. Stridently independent, she felt no conflict of interest befriending her favorite filmmakers (Robert Altman, for one), then reviewing their work in print. And as her cultural cachet rose, so did her self-righteousness. In response to Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), she wrote, “How can people go on talking about the dazzling brilliance of movies and not notice that the directors are sucking up to the thugs in the audience?” Still, this biography is oddly quick to dismiss the homophobic remarks in her reviews as attempts at humor. Kael brushes off the homosexually charged The Children’s Hour (1961) with “I always thought this is why lesbians needed sympathy—that there isn’t much they can do.”

What’s most striking, as Kellow walks us from Kael’s career-making rave for Bonnie and Clyde (1967) through the dawn of blockbusters like Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977), is what she saw in movies. For that brief period, to her, they became our national literature, as expressive and experimental as printed novels. They deserved real conversation, not just lecture-hall analysis or two-thumbs-ups. I felt almost touched reading how movies started to pass Kael by—she really believed she could better them. She never considered herself an artist, but then, much of what she praised was “trash.” Pauline Kael reads like a love story: one titan meeting another, falling head over heels, and finally surrendering.

Josh Garstka is not slaving away at his first manuscript, but has nonetheless published a few poems, recently in Cream City Review and Stirring. He received an M.A. in writing and publishing from Emerson College, and currently works in textbook publishing. His past with Ploughshares stretches back to the early days of this blog.