The Eyes of Writers

“Everything has its testing point in the eye, and the eye is an organ that eventually involves the whole personality, and as much of the world as can be got into it.” Flannery O’Connor.

O’Connor gave this advice to writers, but she could have given it to painters just as easily. What O’Connor knew was that writers are painters with words.

As a visual artist, this makes total sense to me. When I write, I instinctually test everything with my eye. I zoom in and out of my scenes. I pick and choose what I want to highlight. I consider color, perspective, composition, texture—all the elements that an artist would use.

O’Connor was a painter and cartoonist. She knew that a well-drawn picture is worth way more than a thousand words. Imagery is more powerful than expository language.

What we see, whether real or imagined, can have such a deep impact on us it can change our physiology. Today, for example, I saw a great blue heron take flight, and it gave me chills. A vividly written sex scene can arouse our own desires because we can picture it. What we see, and sometimes what we imagine, can move our bowels in terror and fear.

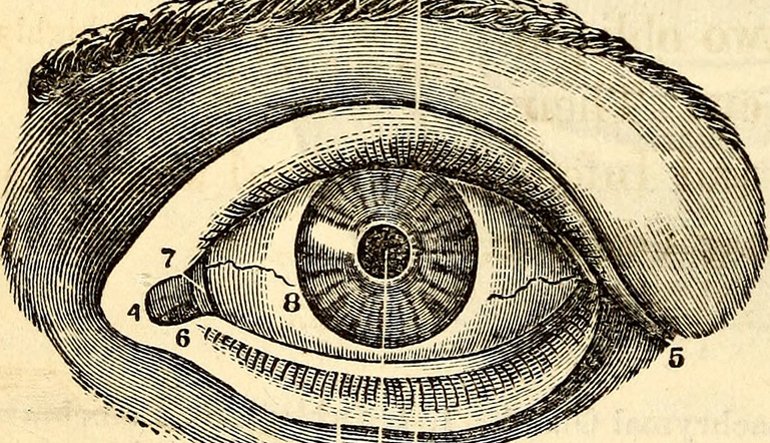

The eyes have this supernatural power in no small part because they work closely with the brain. The eye gathers visual information, and the mind interprets it. It tells us not only what we’re looking at, it tells us how to feel and think about it. Our sense of sight gives us insight into what we see.

Insight is sight beyond original sight. If the handle of an ax is worn, we’d have the insight that it’s been used. If a writer draws our attention to a character’s fidgety hands, we’d have insight into how they feel.

In Hinduism, Taoism, and many other religions and philosophical traditions, this third eye has mystical powers. And it’s this eye that O’Connor is talking about that eventually involves the whole world.

The eye is by far the writer’s most powerful tool, and writers should be mindful of how they use it.

As a visual artist, I protect my eyes. I try not to spend too much time narrowing my field of vision, reading or scrutinizing my phone. And I’m cognizant of the fact that the light from screens can damage the retina and degrade our ability to sleep.

Far more dangerous is the fact that how we use our eyes and what we see with them can trick the brain into having insights that aren’t accurate.

Repeated images of stereotypes can lead us to believe them. Repetitive imagery can normalize things that shouldn’t be normalized like the devastation of war or the existence of poverty.

According to a Nielsen’s report from 2016, on average US adults consume ten hours and thirty-nine minutes of media a day. When the eyes take in too much information all at once, they don’t know where to look or what’s important, and as a result, the brain gets confused. It doesn’t have time to contemplate and understand the data it’s receiving.

Too much visual information interferes with our ability to imagine and create images of our own. And when we live our lives more on screens than in reality, when we spend our time consuming images and information filtered through the eyes of others, when the marketing machine and the capitalist system that it thrives on provide more of what we see than we see ourselves, we allow ourselves to become brainwashed without even knowing it.

It’s in the careful, deliberate consideration of information that we understand the information’s meaning. It’s in the wide view that we see patterns. Our ancestors survived by this, sensing danger by scanning the horizon, reading and decoding the light and shifting winds.

Our understanding of the world depends on what and how we see it. When we don’t step back and assess the details as a whole, we lose our ability to connect the dots. We can’t discern the link between actions and consequences or recognize the cycles, for example, that tell us global warming is real.

The responsibility to organize what we see, to take the randomness of life and reconstruct it into a new form that has meaning, lies squarely with writers and other creative people (scientists and mathematicians alike).

Consider for a moment what To Kill A Mockingbird accomplished: it held a mirror up to our society and reflected our limitations back to us. It made millions of people better people—just by reading it.

When I write, I rely on my ability to see and to discern what’s important and what’s not. I need to know how to step back from my work and recognize its patterns and larger meaning. I depend on my imagination to fully conjure up scenes. I strive to draw characters that aren’t stereotypes but are real. And a writer’s job is not to normalize things that shouldn’t be, in fact, it may be just the opposite.

Flannery O’Connor’s advice is worth repeating: “Everything has its testing point in the eye, and the eye is an organ that eventually involves the whole personality, and as much of the world as can be got into it.”

My advice: give your eyes a rest. Clear your vision. Look off into the distance, soften your gaze, and contemplate the world. If Flannery O’Connor were here today, I am certain she’d agree.