In Praise of Unlikeable Characters

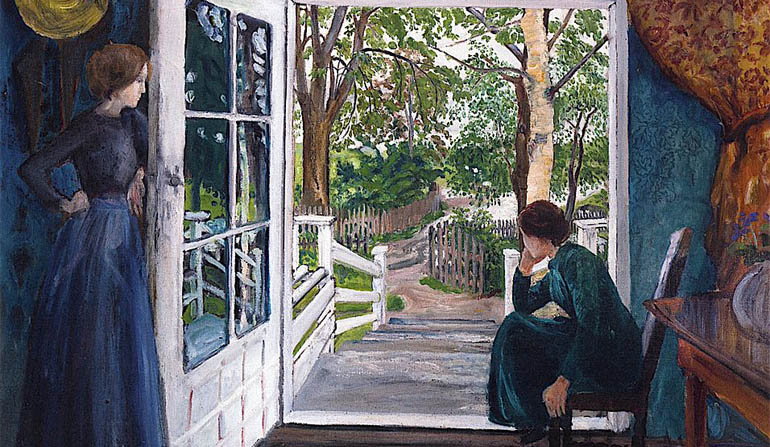

Doris Lessing’s Martha Quest begins, marvelously, with one of the best depictions of adolescent malaise I’ve ever read: the fifteen-year-old title character languishing on her porch in silent, miserable judgment (in “spasms of resentment”) while her mother knits, and gossips vacuously with a neighbor. Even the novel’s epigraph, from Olive Schreiner, seeps bitterly: I am so tired of it, and also tired of the future before it comes. The novel itself is irritable; its prickliness reflects Martha’s, and the author’s own. Martha is incredibly relatable, but she is the variety of character that you hesitate to call relatable lest other people look at you warily. Martha Quest bucks the trend—in much of literature but especially novels about young adults—of pairing recognition with flattery. Martha Quest is a character of a higher order. She is naturally, believably, refreshingly unlikeable.

I once gave the novel to a close friend with similar literary tastes: she surprised me, and hated it. Mostly, she just hated Martha. Martha makes terrible choices; she complains; she is skeptical of nearly everything and everyone who crosses her line of sight. Significantly, Martha is no heroine. Unlike her counterparts in the novels of Lawrence, Bronte, Eliot, Joyce (etc., etc.), her rebellion against the social order is mostly passive (there are eventual exceptions). She doesn’t cultivate inchoate artistic passions. Nor does she seem to care much for other people. She is committed to certain radical political ideals almost inexplicably: not out of valor or altruism but perhaps reluctant duty. Her distaste is the point.

I have always been strongly and sincerely drawn to “unlikeable” characters: Olive Kitteridge, the nameless narrator of Ozick’s Trust, Sam and Henny Pollit. I’m particular about my criteria: I don’t mean antagonists who are reclaimed, with varying levels of irony, like Beowulf’s Grendel, or various Disney villains. I definitely don’t mean antiheroes: there’s plenty to be said about the Walter Whites and Patrick Batemans of literature and film, but that’s not at all what I’m interested in here. Nor am I talking about the underdogs, outcasts, or wallflowers who may be held at arm’s length by their own society but whom we, the reader, are clearly supposed to find awesome.

Liking unlikeable characters. The language around this can get tricky to the point of fatuousness. Our vocabulary of “like” and “dislike” is infantile and pervasive, especially when it comes to other people; equally especially when it comes to any art. It’s common for stories to ingratiate themselves to us cheaply, drawing out easy sympathies with flatly good characters, and I appreciate writers who do what they can to thwart that impulse—walking steadily and gimlet eyed between the dual temptations of hagiography and condemnation. Instead of flattening a stranger’s unique perceptions until they slip unnoticeably into our own—instead of projecting bits of our own ego in a costume onto a story—such writers and their “unlikeable” characters remind us, sometimes even painfully, of the boundaries that persist between people.

It is clear that for Lessing, Martha’s story—a largely autobiographical creation—is both exorcism and apologia. Lessing viewed her own spiritual and moral development as a series of phases that built on their previous incarnations without renunciation, and in Martha she is grappling to balance honest self-examination with an underlying justification: a right to dislike, to be unfair, to be wrong. In an admirably Martha-ian way, she upholds Martha’s superiority even as she undermines it. This is the crux of a great “unlikeable” character: the author’s control, and the choices they make in positioning the character to both themselves and the reader. Lessing does not go easy on Martha, nor does she scorn her. She demands of her art and her readers a tougher sort of observation.

Such characters, intelligently wrought, are more than a cluster of personality traits. They represent a relationship between author, reader, and subject in the same way dramatic irony does. Asking why we should care about Martha, or Olive Kitteridge, or the Pollits, is to understand narrative fiction as no more than reductive, didactic instruction. It is simple for an author to show us a hero or villain and say be like this person, but not that one. To master writing (or reading) unlikeable characters requires acute social observation and a developed sense of morality that is at odds with social convention and hierarchy. It calls on us to interrogate the distinction between morality and mores. It forces us to consider the ways in which we could have become anyone else while simultaneously appreciating that we can only ever be ourselves. It appeals to what Orwell called the “historical impulse,” or what Cynthia Ozick described as “a heritage of common . . . experience” that “universalize[d] ethical feeling.”

Martha Quest is the first of a series of five novels that follows Martha to the end of her life. The last, The Four-Gated City, finds Martha approaching middle age, living in London after the Second World War. Here, after four novels observing a version of Martha that is recognizably a continuation of the original novel’s intelligent, contemptuous teenager, Lessing makes a wise and unexpected choice: Martha, living in a country itself transformed, takes an opportunity to make over her personality. She decides to become likeable. She gets a job as a waitress, calls herself “Matty,” and jokes with her bosses and customers. She morphs almost grotesquely into a kind of sitcom caricature. It cannot last. She goes home every night feeling false, a “jester” who blunts herself dull against her appeal to the crowd, and is miserable.