Black Voices on the Civil War

Although activists have been fighting for the removal of Confederate symbols for over a hundred years, this month’s events at Charlottesville have broadened the national conversation. People are entering their zip codes into websites that will tell them where their nearest Confederate monuments are; some cities are taking down statues in the dead of night. It’s been a long time since the Civil War was water cooler conversation—though that’s clearly been to our national detriment.

As a reader, Charlottesville has me thinking about poems of the Civil War that center black experiences. Poems from the Civil War canon are usually heavy on Whitman, Dickinson, or folk songs like “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” But the following three texts should satisfy anyone who wants to read beyond “O Captain, My Captain.”

Blue-Tail Fly by Vievee Francis

Francis’s debut collection of poems, released in 2006, takes historical figures from the era before, during, and after the Civil War and breathes life into them through persona poems. Everyone from Br’er Rabbit to Abraham Lincoln makes an appearance. The book begins with an exchange of sonnets between Callie, a freed Mississippi slave, and her illegally-wed white husband, Andrew. Newly settled in East Texas (Francis’s native state), the two navigate what it means to be in an interracial marriage, and contemplate their fraught surroundings. Texas snakes slither throughout these sonnets, accruing symbolic weight. For Callie:

Snakes brown as days-old slop

Slid like haints under the boards of the house—

Muddy skins the sun couldn’t wither.

Whistles blowing all around—and hisses

Under your feet. This is what freedom is—

A sinner’s poor choice between what slithers

Over the dripping branch and what you know

Will always make its rattle heard below.

The war is over, but the danger has just wormed its way below ground, waiting to strike.

Poems of the Anglo-African and National Anti-Slavery Standard, 1863–1864

The poetic canon has certainly failed black poets writing during the time of the Civil War. A recent project by RJ Weir and Elizabeth Lorang brings together poems that were published in newspapers of the era—the Anglo-African, a black newspaper, and the National Anti-Slavery Standard, the weekly publication of the American Anti-Slavery Society. (Interestingly, the two presses were literal neighbors, publishing next door to each other on Beekman Street in lower Manhattan.)

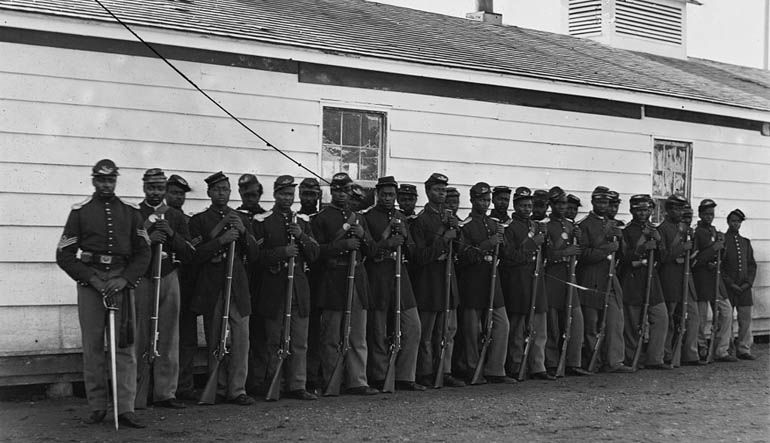

A poem by black activist James Madison Bell typifies some of the motifs that appear frequently in this collection: the attempt to preserve the memories of black soldiers and their contributions to the war, the defiant claiming back of history from being written exclusively by whites. Bell explicitly takes on Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade” and notes that his poem will praise a lesser-known entity: the Black Brigade.

The pleasing duty still remains

To sing a people from their chains—

To sing what none have yet essay’d,

The wonders of the Black Brigade.

Native Guard by Natasha Trethewey

Trethewey’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book mixes personal history with Civil War history. The motif of the photograph dominates the collection; we can imagine the poet lifting the pages of a photo album examining pictures of herself and her late mother alongside images of black Civil War soldiers. A native of Mississippi, Tretheway is particularly interested in the 1st Louisiana Native Guard, a regimen of free black soldiers who fought on the Union side. This is a book about middle ground—the poet is mixed race and grew up in the Deep South. (Trethewey’s early poem “White Lies” describes her ability to pass as white, set alongside a fear of telling lies instilled by her mother, who punished her by washing out her mouth with Ivory soap.) The soldiers are in this middle space, too—freed black Southerners, fighting for the “wrong” side.

What interests the poet most is reclaiming forgotten history. In “Elegy for the Native Guards,” the speaker describes a trip to Ship Island in Mississippi, the site of Fort Massachusetts, which was held first by Confederate soldiers, then Union ones. She comments wryly that upon arriving she finds a monument to “some of the dead”:

The Daughters of the Confederacy

has placed a plaque here, at the fort’s entrance—

each Confederate soldier’s name raised hard

in bronze; no names carved for the Native Guards—

2nd Regiment, Union men, black phalanx.

What is monument to their legacy?

All the grave markers, all the crude headstones—

water-lost. Now fish dart among their bones,

and we listen for what the waves intone.

Only the fort remains, near forty feet high,

round, unfinished, half open to the sky,

the elements—wind, rain—God’s deliberate eye.

We see you, the poem’s ending says. We see the neglected black soldiers, unpraised and hardly remembered, and most of all, we see the country that remembers the Confederate soldiers who died there and not the courageous Southern black men who broke with their neighbors to fight for the right side.

Trethewey’s question—“What is monument to their legacy?”—haunts, and takes on renewed urgency in light of recent events. Through poetry, at least, we can begin tearing down old symbols of hate, and building new ones to those whom posterity has wrongly neglected.