Tending the Shared Garden of Immunity

In 2014, Eula Biss published On Immunity: An Inoculation, a work of literary nonfiction that considers the history and controversy surrounding vaccination. Part memoir, part history of medicine, and part literary criticism, On Immunity draws inspiration from sources as wide-ranging as Greek myth, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and the peer-reviewed journal Science to unravel a web of beliefs about the body, disease, and infection. In the wake of the discovery of the novel coronavirus and outbreak of COVID-19, I decided to re-read it. Six years after its original publication, I thought Biss’s book might feel dated, but it proved to be a worthwhile read in these difficult times. If anything, its themes feel even more relevant now. In trying to understand immunity as concept and metaphor, Biss reveals the profound ethical dilemma that has always inscribed itself into the vaccination debate, which, at root, is about the relationship between self and other, between individual bodies and the social body.

For Biss, immunity represents something larger than simple protection from disease. She recalls the myth of Achilles, whose mother Thetis, a goddess who married a human, dipped him in the River Styx, rendering him impervious to injury except for the small patch on his heel where she had held him. According to legend, Paris’s arrow shot through Achilles’s heel, killed him at Troy. The immortal mother tried to transfer immortality to her son but failed. Immunity, Biss understands, is a dream of immortality, the desire to shield ourselves from both injury and infection. This is not possible for any of us, but we can’t help but seek it out.

We have been strategically avoiding disease contraction for hundreds of years: the word vaccination can be traced back to late seventeenth-century England, where folklore held that milkmaids who had cowpox on their hands were strangely immune to the dreaded smallpox; “vacca” is the Latin word for “cow.” The process of inoculation, Biss points out, came to North America via ministers who learned of it from their African slaves. Originally known as variolation, over time it became known as inoculation. She writes:

When Voltaire wrote ‘On Innoculation,’ the primary meaning of the English word inoculate was still to set a bud or scion, as apples are cultivated by grafting a stem from one tree onto the roots of another. There were many methods. . . but in England it was often practiced by making a slit or flap in the skin into which infectious material was placed, like the slit in the bark of a tree that receives the young stem grafted onto it. When the word inoculate was first used to describe variolation, it was a metaphor for grafting a disease, which would bear its own fruit, to the rootstock of the body.

Throughout On Immunity, Biss remains attuned to the ways that our understanding of immunity is tied, inescapably, to metaphor. Biss herself seems to be in search of the most helpful metaphor though which to express what she is trying to say about the vaccine controversy, and what this says, by extension, about how we understand immunity. Vaccines trouble us, she posits, because they involve needles that penetrate our skin, vampiric incursions from the outside world that remind us of our mortality. State-mandated practices of vaccination bother us because they represent governmental control over our private bodies.

Herd immunity is an especially important concept for Biss, and one that has taken on a new meaning to all of us in the past few weeks. By its very definition, herd immunity exemplifies what Biss wants us to understand about the relationship between individual bodies and the larger social body. In order to shield the most vulnerable from disease, those of us healthy enough to do so receive inoculations against a number of illnesses that were once greatly feared and that we have, in just a couple of generations, largely forgotten about—polio, diphtheria, measles, even chickenpox. While there is a small possibility of a poor response to any vaccine for a given individual, the benefit to society as a whole is immense: when a large enough percentage of the population is vaccinated, herd immunity is achieved, making it much more difficult for a disease to spread widely. Of course, herd immunity can also be achieved without the aid of vaccines, instead of as a result of individual exposure to pathogens, but this method comes at a much higher cost to the population.

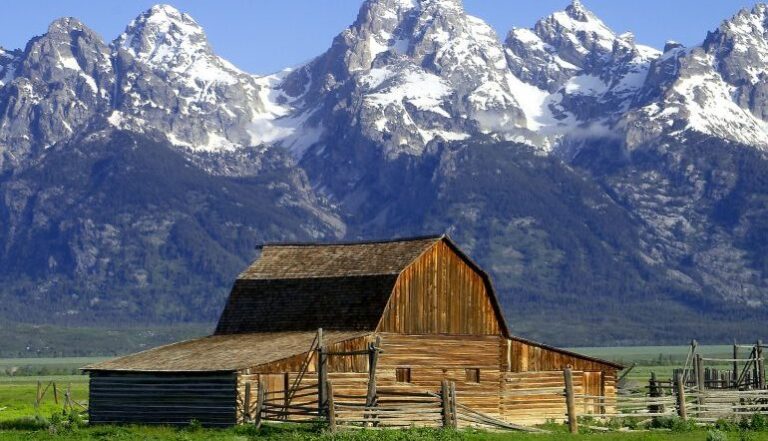

Now, then, we eagerly await a vaccine against COVID-19. Perhaps it’s hard to remember that just a few years ago—at the time Biss was writing—infectious disease did not seem like much of a threat, that these ideas might have seemed mostly theoretical, an obscure moral quandary. Yet as most of us hunker down in our homes, restricting our movements not just for fear of catching the virus but so as not to pass it on to others who may suffer greatly, Biss’s work appears prophetic. Our attitudes toward immunity are mediated by the ways that we conceive of our bodies in relation to others; do we conceive of ourselves as closed systems, or as parts of a larger whole? Biss writes that most Americans “tend to prefer a frontier mentality in which we imagine our bodies as isolated homesteads that we tend to either well or badly.” We see this “frontier mentality” in the photos of young people reveling on beaches for spring break, at a time when many state governments were urging us to “shelter in place” and practice “social distancing.” Like the mothers who decide they are unwilling to vaccinate their children against a number of diseases because of the small risk posed by vaccines, the spring breakers were thinking of the illness in terms of the threat it posed only to their own bodies—not the threat that they might pose to others as disseminators of the virus.

As Susan Sontag does in her 1978 work Illness as Metaphor, Biss notices the ubiquity of military language used when discussing disease. Even among immunologists, Biss notes, these metaphors are so ingrained that they have ceased to seem like metaphors at all. Many of us now refer to healthcare workers as “on the frontlines” and our society as “at war” against coronavirus. This language is perhaps inevitable, Biss suggests, in a society as martial as our own, but it also traps us in a simple binary of good vs. bad, healthy vs. infected, self vs. other. Biss finds reassurance in the fact that our bodies cannot exist as closed systems—that no matter what, we remain connected to other people and to our larger environment. Vaccination itself, she points out, is “a system not actually typical of capitalism. It is a system in which both the burdens and the benefits are shared across the entire population.” For Biss, vaccination and herd immunity are beautiful for the ways that they connect us, transcending our preference for easy binaries. She subtitles her book An Inoculation as if attempting to immunize herself against these binaries, and against the selfish impulses that might push her to protect her own family at the expense of the larger community.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the ultimate metaphor that Biss adapts for her understanding of immunity is that of the garden—a place where nature may flourish under controlled circumstances and, “where, under the right conditions, we live in balance with many other organisms”:

If we extend the metaphor of the garden to our social body, we might imagine ourselves as a garden within a garden. The outer garden is no Eden, and no rose garden either. It is as strange and various as the inner garden of our bodies, where we host fungi and viruses and bacteria of both ‘good’ and ‘bad’ dispositions. This garden is unbounded and unkempt, bearing both fruit and thorns. Perhaps we should call it a wilderness. Or perhaps community is sufficient. However we choose to think of the social body, we are each other’s environment. Immunity is a shared space—a garden we tend together.

One of the things that the novel coronavirus has revealed to us, for better or worse, is our interconnectedness, our mutual dependence on each other. Many people have noted the paradox that we are now isolating ourselves from one another for the sake of the larger community. Whether this pandemic will help Americans to shift away from a focus on rugged individualism and isolationism toward a more communal understanding—whether we can adapt Biss’s vision of our bodies as gardens among other gardens—remains to be seen. Moreover, as I write this essay, I am aware that metaphors may seem like weak props in times such as these, that garden imagery may seem particularly futile as our hospitals fill up with the sick. But for those of us stuck in our homes this awful spring, waiting, attempting a great experiment at creating a unique kind of immunity, united in our isolation, I think there is hope in Biss’s words. May we all learn to take better care of each other’s gardens.

This piece was originally published on April 13, 2020.