Two Boston Commons at Twilight

Susan Minot’s arresting story “Boston Common at Twilight” focuses on Ned, a man looking back at a seminal moment in his youth. Included in her recent collection, Why I Don’t Write, it begins with a memory of Boston Common; the trees there would become a stand-in, of sorts, for a day that represents a break in his life, a day when he was fifteen, a day when his path took a dramatic turn. The story shares its title with the Childe Hassam painting from 1885-86, which is formally called At Dusk (Boston Common at Twilight) and is part of the permanent collection at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. Although Minot does not refer to the painting in the story, there are a number of ways that both works are linked, and seeing these connections both underscores the themes that run through the story and allows the viewer to see the painting anew.

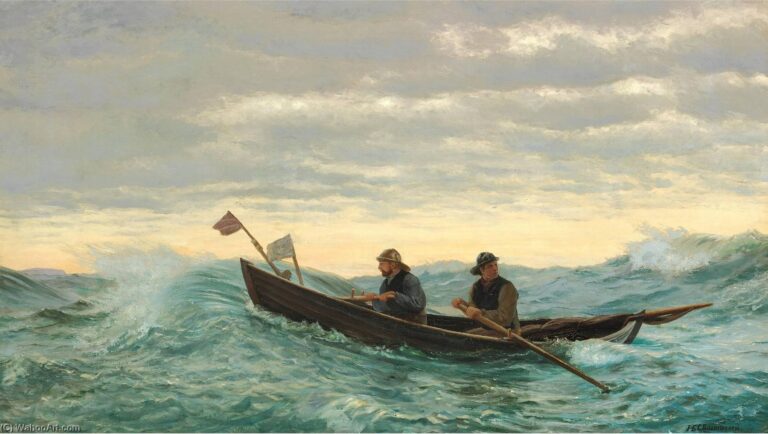

Hassam’s painting has become an iconic image of winter in Boston. Although it was created 135 years ago, the mix of pristine and dirty snow, the late afternoon light, and the busy city running alongside the calmness of the Common are all familiar to the contemporary viewer. You can feel the stinging cold on your cheeks; you can practically smell the cigar clenched in the mouth of the man on the path. The angle of the sun in the sky has led researchers to believe it represents a late December afternoon. Hassam shows a city in transition: the horse-drawn streetcars backed up one after another on Tremont Street; tall, new buildings pushing in on the Common from the left; electrified lights brightening the sky. The eye is drawn initially towards the front and center, where three figures are highlighted—a woman and two small girls—before being pulled to the back of the painting by the geometric lines of the trees, streetlights, and benches. In a review of a Hassam retrospective in 2004, John Updike beautifully describes the scene as follows: “In the west an orange glow through the trees signals the passing of sunset; city gloaming, the suspenseful moment as darkness descends and life moves to the lighted indoors, becomes elegiac.”

Minot features these same trees as bookends in “Boston Common at Twilight.” The story begins with Ned remembering the trees, and his memory of them aligns with the trees that are seen in the painting:

Much later, it was the trees he would think of.

They had been so tall and bare. He would have seen them when he’d first gone to the Boston Common when he was eight years old, but he didn’t remember noticing the trees then. Now, when he thought of that day in December, he would see the spaced-apart oaks with their spidery branches, reaching into the stark afternoon, leafless black skeletons, towering above him. But oddly he would picture them from above, looking down through the branches to his fifteen-year-old self, beside the melting snowbanks and the other people teetering around on the park paths.

Minot often beautifully uses landscape to explore the interiority of her fictional characters. In this story, it is 1980, and Ned is on Christmas vacation, although he hasn’t yet returned to a suburb north of Boston because he still has hockey practice at his boarding school, and because of “everything going on at home.” He is staying at his aunt’s house in Cambridge, but on this day he walks to the Common from North Station with the hope of buying weed, as he has heard from his friends at school that this is the place to do so. He wants to impress his older brother Matt with his purchase.

Approaching the Common via Government Center, Ned’s initial view would have been very similar to that of the painting. As he arrives at the Common somewhere near the Park Street T stop, he remembers his earlier visit there, seven years ago, with his mother and brother, when they rode the swan boats in the spring, “dressed in their Boston clothes, gray flannel shorts with suspenders underneath their sweaters.” Their mother, too, was dressed up, wearing “a dark pink dress with a matching jacket, and her pearls.” The family rarely came to the city, so this was a special outing, which also included sundaes at Schraft’s. They were tourists and outsiders, and although Ned found the city “cool,” he was disappointed in the swan boats: they “weren’t really swans the way Ned had imagined them; they just had wood cutouts on the side in the shape of swan silhouettes with wing-tipped tails.” Minot seems to be drawing a parallel between the way things appear and the way things actually are.

The woman and the girls in the painting are also carefully and elegantly dressed, especially the older girl, who is featured more prominently, feeding the birds. The younger girl is standing back, watching. The woman—perhaps the mother, perhaps a governess—has her left hand extended. Is she holding the younger child back? Or is she urging the older child to move along? Erica E. Hirshler, a senior curator at the MFA, notes in her MFA Spotlight Series book on the painting that the mere presence of women and children out late in the darkening day was something relatively new in the city in 1885; the electric lights provided safety for women who were increasingly independent. Still, they were cautioned to dress appropriately, and the woman here, in her modest dark brown outfit, has done just that. In Hassam’s world, women and children are novel additions to the urban landscape.

The three figures in the painting are echoed in the story by Ned, Matt, and their mother. Matt is clearly the older child, more confident and ready to face the world, while Ned is hanging back, observing. When their father tells Matt and Ned that he has fallen in love with another woman and has no choice but to leave their mother, Matt—who has been studying philosophy at school—responds, “‘You can stay or you can go off with some other lady. There’s always a choice.’” After their father leaves, their mother falls apart and starts heavily drinking. When Ned was younger, he appreciated that his mother “knew what it was like to be a kid.” On that earlier trip to the Common, Ned’s mother, like the woman in the painting and like Ned himself, was an observer: “She was happy watching Matt eat his hot fudge and Ned his butterscotch and stole bites with her spoon.” But now, as Ned is older, “he sort of wished she were more like a grown-up.” He seems to be longing for a parent to shepherd him through these teenage years. Their father—not present on that earlier trip to the Common—has also largely disappeared from Ned’s life since he left his mother. In both the story and the painting, there is an absence of a prominent male figure.

Unfamiliar with the Common, Ned stands near a trashcan under those “amazingly tall trees” and eats a Snickers bar, a heartbreaking evocation of a boy on the verge of becoming a man. A woman approaches him, and Ned notes the woman’s appearance carefully, particularly the shades of red and brown around her: “She wore a rust-colored leather jacket belted at the waist and narrow blue jeans with a flair. Her sunglasses were tinted brown, darker at the top. Each cheek was smudged with a brownish rouge. Sienna, he thought, knowing the color from his oil-painting art class.” This description feels like a very direct link to the painting. First, the woman’s dress is being noted, perhaps in comparison to the woman in the painting. The colors described echo those in the painting, as well, and the palate that Hassam favored during this period in his career. And finally, the fact that Ned is taking not only art classes at school, but specifically an oil painting class, seems very pointed. It makes sense, of course, that he is an artist, someone who, like Hassam, uses his keen eye to watch and record. From his opening description of the trees, Ned has shown his ability to show the world around him in exacting detail.

The woman, after offering to sell him pot, takes him down into the subway—which now runs directly underneath Tremont Street—and then, with a knife, convinces him to go to Charlestown with her. In her apartment, she assaults him. During the attack, as he lies on her pink satin bedspread, he looks out the window and sees the Bunker Hill Monument, the site of one of the first battles in the Revolutionary War. He is too frightened to fight her. Unlike Matt, he doesn’t believe he has a choice to do anything but to let this run its course. He is powerless and alone.

On President’s Day—a child’s world marked by holidays from school—Ned finally tells Matt what happened. Matt is angry and wants justice, but Ned lies and claims he can’t quite remember where the woman lives. His guilt at his inaction is enormous: “He still felt he’d been the one who had allowed it to happen, and no matter how you saw it, it would always be that way.” What the boys do agree on, however, is that they are alone with this information. There is no one they can tell, even though they know they should.

The following day, the boys visit their mother in a rehab facility, the children becoming caretakers for the parent. Ned thinks again of the trees and also of the pink bedspread in the woman’s apartment, having the sensation of the event happening to someone else, in much the same way that he remembers the trees as if from a great distance, looking down. Then the story quickly leapfrogs decades, and we now understand how that day and that year inform who Ned is in the present moment. His mother, better now, is taking care of him.

In this flash-forward, the story redefines the coming-of-age arc: the boy who didn’t have the support of his parents in a time of need is now a man, but a man who got lost in his boyhood. He may have his mother now, but he needed her then. The coming-of-age narrative in the painting is more traditional and more optimistic: the city is developing and changing, the newer buildings on the left exerting pressure on the bucolic park on the right. In the middle lie the woman and the children with the older child venturing out, ready to cross the divide. Updike described the fact that the canvas is almost split in two, like “an open book.”

Twilight, after all, is that divisional moment that sits between day and night. In Hassam’s painting, the sun has just set, the reflected light still glowing pink in the windows and on the snow. There is beauty in the late day landscape. Although the city is pressing up against the Common, nature prevails. For a contemporary viewer, there is also quiet comfort in the familiarity that exists, in the way that things have remained the same. It is a moment that exists across time, an idealized image, perhaps, that romanticizes both the past and the present. It is partially for this reason that the painting is so loved and admired.

In Minot’s story, though, the slip from day to night reveals, instead, the underside, the darkness to come. For Ned, the Common is not a beautiful place—it is a place to buy weed to impress his brother. It is, later in life, a memory of a place and a time laden with pain. Now, his recollections are filled with “spidery branches” and “leafless black skeletons.” In hindsight, we can see how his description of the trees is colored by his assault. And his brother, like the older girl in the painting, has moved on, with a family of his own. Ned is left alone, yet again, returning to his dark memories of the day when everything went awry.

Certainly, in Hassam’s world too, horrible things happened to young boys who weren’t quite ready to take care of themselves, who had sadly been left very alone. But although Hassam wanted to portray the city as he knew it, he was more interested in softening the reality, in showing the beauty in the landscape, in capturing a moment in time. We will never know what happens to his figures when the sun finally disappears. Minot, in choosing to echo the title and certain elements of the painting in her story, seems to correct this, in part, to subtly juxtapose her story with that of Hassam’s painting. She is interested in an unvarnished exploration of the arc of a life, in the way that a simple choice made by a sensitive fifteen-year-old boy can change his life forever.

Minot’s story is heartbreaking, and it stands beautifully on its own. But understanding the connections between the Hassam painting and the story only serves to deepen the meaning of both. The promise of the young girls in the painting is contrasted with Ned’s dark journey into adulthood; the optimism of the romantic past is set against the pessimism of the present. It is difficult, now, to look at the painting without seeing the darkness that lurks within it, or to read the story without yearning for the innocence of youth and an earlier time. The Common in winter, of course, marries the two together across time: the cold snow, the rosy light from the setting sun, and those familiar, ancient trees.

This piece was originally published on January 5, 2021.