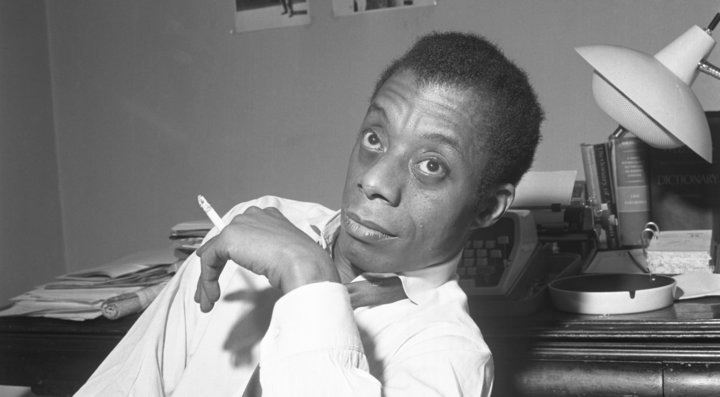

Reading Baldwin after Harvey: Why Climate Change is a Social Justice Issue

In the wake of Harvey, I’m reading the title essay from James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son (Beacon Press) with my freshmen. The first lines go, “On the 29th of July, in 1943, my father died. On the same day, a few hours later, his last child was born.” Someone goes whoooooaaaaa. What does Walter Mercado have to say about this?

Everyone laughs—we need to laugh—or at least everyone who is vaguely familiar with Mercado, a staple in Spanish language homes in Houston. Mercado is a lot of things, but he’s perhaps best known as the guy who captivates everyone’s superstitious tia or ’buelito. He’s possibly the most famous TV astrologer in Latin America. People take him seriously. And I mean really seriously.

Freshmen always have an interesting way of connecting the dots in subconscious ways. While we take a moment to poke fun at Mercado—and by extension our superstitious aunts and ’buelitos—we unpack shades of those same generational rifts that Baldwin explores between himself and his father. But we’re unpacking something deeper too—the imagery of the 1943 Harlem riots which, as one student points out, isn’t unlike the imagery all around us in post-Harvey Houston. Talking about the riots, Baldwin writes:

Sheets, blankets, and clothing of every description formed a kind of path, as though people had dropped them while running. I truly had not realized that Harlem had so many stores until I saw them all smashed and open; the first time the word wealth ever entered my mind in relation to Harlem was when I saw it scattered in the streets.

Moving through Houston today, it’s easy to spot piles of debris—soggy sheetrock, splayed insulation, discarded clothes, crusting blankets, expensive waterlogged furniture baking in the humidity and sun. The debris lines the curbs, waiting to be collected. Seeing it all unpacked, I would have never guessed there was so much stuff in Houston. But there it is. Waiting to be collected, all of that money hauled off to some dump.

Of course, the circumstances between Harvey and Harlem are different, but the fault lines exposed by those events are not.

Concerning Houston, we know now that while the storm largely affected everyone, the poorest (including many people of color) are still the ones left in the shelters. While FEMA assistance is available for those who had the means to own a home, those who didn’t now face the bare-knuckles market that is the newfangled housing shortage. While the financial center of downtown Houston largely avoided catastrophic flooding, unscrupulous land speculators exploited poor brown and black Houstonions who couldn’t afford not to live in floodplains, especially in the vicinity of the Addicks and Barker reservoirs. While documented people had the option of fleeing Harvey or sticking it out at home, undocumented people were either corralled as they tried to evacuate or were otherwise left to their own devices for fear of Border Patrol who maintained a presence near area shelters.

The connective tissue I think my students were trying to articulate between Harvey and Harlem goes beyond just the surface of that image. It goes as deep as what that image represents: a riot as a communal expression of frustration with white control over the black body (and by extension black dignity) through systems of oppression, financial and otherwise.

In Notes of a Native Son, the Harlem riots can be read as the black body asserting its dignity over white capitalism. The catalyst for the riot is the murder of a black soldier by a white policeman. It’s no accident that in the essay, white-owned business are primarily targeted. That obscene amount of wealth in the face of poverty is targeted. The financial order of white landlord/white business owner leeching off the black community is overturned.

Echoes of that frustration ring out in the classroom as we discuss it. And then we get off on another discussion with Harvey in the backs of our minds: Why were homes ever built and sold in those flood planes to begin with? Which banks, businesses, or people owned that land before? Why is flood insurance so expensive? Why was the financial center of downtown designed not to flood, but the rest of the city wasn’t? Why do the reservoirs empty out into the poorest parts of town? How can that much community wealth be wiped out in a matter of days? But more importantly, who were the people who profited?

In these questions we’re talking about Baldwin, but of course we’re talking about dignity. In the context of my class, Latino dignity specifically. And as my students vent, it suddenly dawns on me: that climate change is a social justice issue too.

Currently, Hurricane Maria is bearing down on Puerto Rico as I write this. It’s just the latest superstorm, one of four in the past month alone, that climatologists are measuring as increasingly larger and increasingly more destructive. Harvey alone dumped 33 trillion gallons of water over Houston, enough to cover the entire state of Arizona in one foot of water. And yet there are still those invested in denying that climate change is real. But why? How?

While at once we’re raging against the systems that made our communities vulnerable to the storm, we must acknowledge that climate change denial is systematic in the way it strips dignity from vulnerable communities of color not financially equipped to deal with the fallout of those superstorms. And occasionally, even among climate change believers, the rhetoric of oppression is used to place blame on communities of color for simply being (read existing) in the path of destruction.

When a superstorm hits, news anchors, pundits, and analysts of various stripes go on the scene with their spotless LL Bean boots and cable news TV slickers to ask—in so many words—What did you do that this happened to you?

At first, the questions are familiar: Why did you buy here? Why not evacuate? Are you going to hunker down? And then they become weaponized: Do you not bear any responsibility for your family’s safety? Do you know [are you too dumb to know] that this storm will kill you? How do you think your family feels about that?

In that way it’s easier to say, they brought it on themselves. They deserved it. Which comes from the same place in the heart as denying service (as Baldwin writes about) or denying someone their dignity. An all too convenient diffusion of responsibility too for climate change deniers—this is a socioeconomic/race/class problem, not a climate change problem. Those red herrings conveniently detract from the truth.

Linking back to wealth, it’s obvious but it should be said that energy companies have the most to profit from denial. Historically that’s been the truth. But also, there are systems that have historically contributed to and sometimes benefited from the fault lines exposed in the wake of Harvey. With recovery efforts run by energy czars already underway, it seems as though there’s an inferred emphasis on the recovery of the energy system which is, in effect, an emphasis on the preservation of white wealth tied up on that system. Though that’s an essay for another time.

I think the images of Harlem and Houston are more interlinked than not. Two different catalysts, but one similar struggle for dignity. And I think it’s worth it to ask how brown and black dignities are being considered in light of climate change. It’s time we start thinking, too, about climate change’s systematic denial and what those who deny its existence have to gain.

This piece was originally published on September 25, 2017.