3 Chapbook Reviews: Own Your Past, Believe The Present, Anticipate the Future

For August, I read three chapbooks that dealt with ideas of past, present, and future in both overlapping and contrasting ways. They also each somehow dealt with ideas of spaces that became place for the writers, though sometimes these places were more about time than physical geography, hence why the past-present-future themes were more apparent to me when it came to thinking about what they each shared.

The Walls They Left Us by M.J. Gette (Newfound, 2016) won the Gloria E. Anzaldúa Poetry Prize, which is awarded “to a poet whose work explores how place shapes identity, imagination, and understanding.” The poems within it conflate the natural world with human crafts and construction, explore false binaries perpetuated by limited critical thinking, and address issues of colonialism, education, and historiography—yet at the same time, the poems so often seem to be love poems or poems nostalgic for lost love. This love, though, could be for another human or perhaps the sea or the moon or a place.

What is evident in Gette’s ideas of place are sprouting seeds of ecopoetry and the ideas that stasis does not have to mean standing water, that maintenance of a land and its peoples is work. In a longer poem titled “Famine Fields,” Gette addresses “How we think we own the world we inhabit,” (23) a powerful line that is almost a response to the refrain “How does it go?” as though the speaker were asking the words to a song.

The chapbook concludes with a long, more narrative and stream of consciousness inspired poem that details a trip to Aztec ruins and places the narrative of the speaker as a tourist with a connection to the place within historical time, something many other poems at times grapple with. The narrative follows a friend, M., through this poem, who often speaks existentially, “We want to be owned, but we also want to be our own proprietors” (33). The poem looks at the layers of humanity that the setting, its speaker, and her friend exist in as one would look at the rings of a tree, taking everything from the past possible to see into consideration and then turning the mirror on one’s self there and then into its future, where “We don’t know there is an end to things. All we know is that we are looking for one” (35).

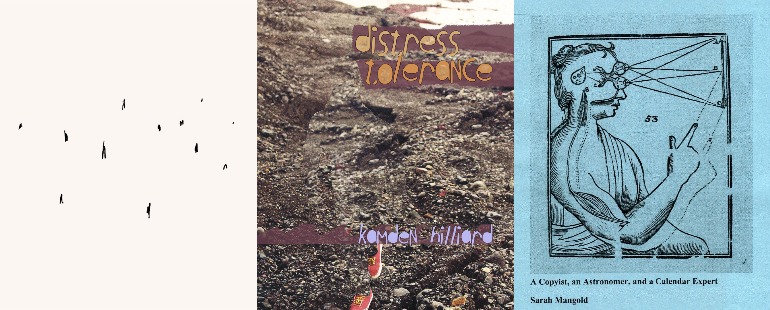

Distress Tolerance by Kamden Hilliard (Magic Helicopter Press, March 2016) concerns itself with identity, often linked to place, though more often connected to one’s place in the world. Hilliard is constantly struggling with how they see themself in relation to others but also how others see them: “i can’t // be dark mostly man and gay because i don’t know who to hate most / and i’m never sure who hates me more” (3). These three not conflicting but difficult bodies to live in under one body make them feel like life is a show or performance of sorts.

On top of the truths we get of Hilliard’s internals struggles with identity, the book is also laced with what it means to contend with trauma: “if trauma is present / then all yeses are henceforth tremulous / and questionable” (6). Turns of phrases like this keep the music in Hilliard’s work, which is often all over the page and sometimes uses non-standard spellings one is more likely to see in text message or online these days. These quirks make the poetry feel alive rather than juvenile or flat, as the omnipotence of the internet is a reality so many of us live with.

James Baldwin is consistently addressed throughout this chapbook almost as a guardian angel or saint of sorts, though a variety of popular culture is referenced, from MTV to Hart Crane to superman. There is something of Allen Ginsberg in these lines as well, especially when they give directives followed by exclamation points, as in “Just Call the Bank”: “i am right and showered in trigger warnings / egg me Bronxville boys! give it to me power me full of evidence and hard / thank you apocalypse!” Where Gette’s strengths were in looking from the past to understand the present, Hilliard is preparing for their future—and preparing us to face ours—with their saints of the past and saints of the present leading the way.

In A Copyist, an Astronomer, and a Calendar Expert (above/ground press, March 2016), Sarah Mangold deals mainly with landscape: clouds, mountains, trees, and how these, though so different from state to state, country to country, render themselves similar in ways that help connect, particularly to each other but also to art, as in “:Originality Is a Working Assumption:” when she writes, “cloud a punctuation / mark torn apart by a miracle: extract saint from common space.” The saint here is birthed by the mark of something common (a cloud) but simultaneously extraordinary (the miracle).

Mangold’s universals are most often found in nature and the idea of it as a system. In “Speak and I shall baptize you,” the poem containing the line that is the chapbook’s title, she writes: “the history of the system is itself a system / rent in human space / liberated from all lawns.” These lines help lead a reader to the understanding that when we look at and try to understand the earth and its creatures—including humans—no matter our expertise, education, or career choice, we can only ever do so from our own present reality.