A Gift of Sorts

This story starts in the tall-walled house of a local poet. Aluminum foil trays of lasagna. Iceberg lettuce. Wool ties, snug dresses. Evidence of an after-party. New arrivals clutch the necks of wine bottles. Out on the dark street, stretched back off a busy thoroughfare, a porchlight illuminates the bumpers of sedans, including my wife’s car, which we both in rode here, and the car of a close friend from grad school. We are all here together to celebrate the visitation of the poet Edward Hirsch. He has just kicked off our annual book festival. He has just read from his most recent collection, titled Gabriel, an elegy to his recently deceased son.

This story starts in the tall-walled house of a local poet. Aluminum foil trays of lasagna. Iceberg lettuce. Wool ties, snug dresses. Evidence of an after-party. New arrivals clutch the necks of wine bottles. Out on the dark street, stretched back off a busy thoroughfare, a porchlight illuminates the bumpers of sedans, including my wife’s car, which we both in rode here, and the car of a close friend from grad school. We are all here together to celebrate the visitation of the poet Edward Hirsch. He has just kicked off our annual book festival. He has just read from his most recent collection, titled Gabriel, an elegy to his recently deceased son.

He always liked to go higher and higher

We’re here he’d say lifting his hand

To the middle of his chestBut we need to go here

He continued on

And raised his hand up to his neck

It is rare in Vermont for so many poets and literary scholars—full profs, associates, assistants, lecturers; writers of various collectives; people with varying aggregates of stories or poems in the digital slush piles of journals—to occupy the same tight space. Talk is intense, merit-based. A hard-laughing post-colonial scholar from the DRC tells of recent hijinks on a New York trip: a famous writer took him out into late-night Harlem then disappeared into the crowd. A new father, a towering David-Wallace-looking figure, describes to me the system he’s developed for interviewing local homeless people for an upcoming collection. At the long wood mess table three women, as if each has access to private knowledge, list to one other the awards and honors bestowed upon Mr. Hirsch. That is how they name him, in the third person, Mr. Hirsch. His books have been fanned across the table. His hand has been gripped, his face thanked. The real, breathing, embodied Mr. Hirsch sits ten feet west at the table’s head, slump-shouldered, quiet, signing the book owned by the woman to his right. Another woman presents to him a copy of her own book, one she wrote, a collection of poems. He sets it beside his paper plate. It is sealed in festive ribbon.

He clung to the couch he held fast

To the chair we dragged him out

Of the closet kicking and screamingFor an after-school ritual he rushed around

The house turning over the furniture

And throwing books at the wallHe pushed over a lamp and tossed pillows

Through the door he nearly broke down

He kicked out the window twice

My wife, a clinician and visual artist, feels out of place here. I know more people and I feel out of place. It is all so sonorous and zealous and fun. We stand with our friend in the dining room’s corner, seven feet to Mr. Hirsch’s side. It’s hard not to lean in, as if gravity has shifted vector suddenly to latitude. Above us hangs the framed portrait of a book by the house’s poet, an exceptional host: jovial, competent. He talks to each person, laughs at each joke. Only once does he make us move so he can squeeze more glasses from the cabinet.

Lord of Misadventure

I’m scared of rounding him up

And turning him into a storyGod of Scribbles and Erasures

I hope he shines through

Like a Giacometti portraitI keep scraping the canvas

And painting him over again

But he keeps slipping away

The woman with the signed book has been replaced by the Wallace figure. He apologizes to Mr. Hirsch, asking what the book is about. Mr. Hirsch says it’s a book about his dead son. Wallace explains that he took care of a sick parent. It was trying, he was young. He promises to read the book. Don’t, says Mr. Hirsch, it’s too sad.

Of course all this time we wonder if we should approach him, standing in the limbo chiseled out for readers in the presence of a writer they admire. It’s a messy confrontation. To reach out is to risk seeming self-involved, celebrity-fawning, desperate. But to say nothing is to risk driving home with the silent sense that something has been left at the house.

Something about amputating your arm

Because it bothered you

It was never a wing anywaySomething about amputating your leg

Because it hurts

You will never walk away from this

I sidle up to the vacant left bench of the mess table. My wife, more confident, sits down. After another minute with Wallace Mr. Hirsch turns to our eyes. I thank him for having written Gabriel. He doesn’t hear so leans in, his palm cupped to an ear. What begins is a conversation with a man who is attentive, patient. I explain that I grew up with my own Gabriel, that I love her, that she is still alive. Mr. Hirsch asks my wife about her work, about the frustrations and joys of counseling teenagers; he blesses her. He describes to our friend the otherworldliness of coming home to a shower door lifted clear off its hinges—why would Gabriel do such a thing? Not one of us knows, but together we laugh at the absurdity. What a silly thing to come home to.

I had to stand on a stepladder

To reach him I couldn’t tear myself away

From leaning down and kissing himOn the eyes the forehead the cheeks

The lips colder than ice

The wretched soundStarted coming out of me again

He was there in the coffin

He was not there in the coffin

It doesn’t occur to me on the ride home, or the next morning, recounting the evening with my wife, or, weeks later, rereading Gabriel, or reading Mr. Hirsch’s profile in the New Yorker, written just before Gabriel was published. He tells the profile’s writer, Alec Wilkinson: “I used to believe in poetry in a way that I don’t now. I used to feel that poetry would save us. […] Art can’t give him back to me. It comforts you some, better than almost everything else can, but you’re still left with your losses.”

It finally occurs after revision and revision of this, this small written gratitude to Mr. Hirsch. It’s the honesty, the kindness, the presence—poetry made manifest before us three hardworking apprentices. It was the same way he treated Wallace, the woman with the book, the poet who gave her collection. The same fragile, well-packed gift that in order not to break you must spend so much time unwrapping.

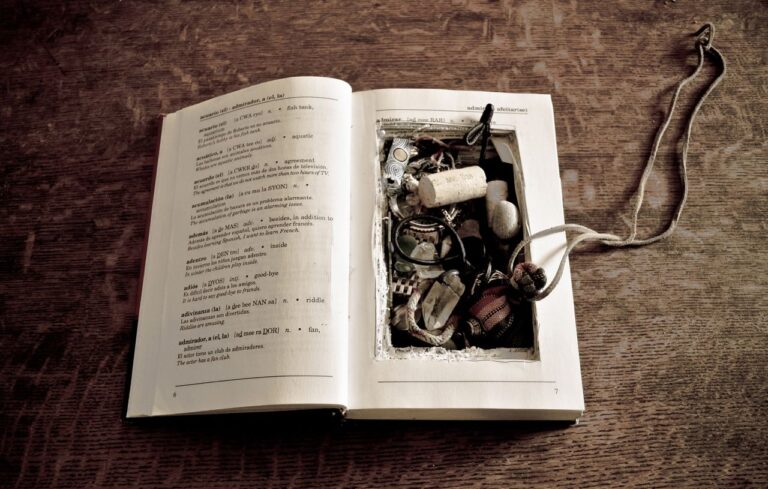

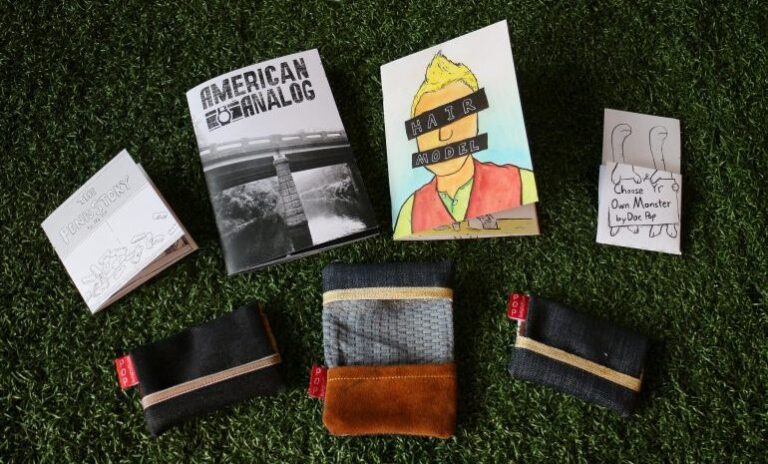

Image: Found poem on collage, by Sarah Kulig