A Held Breath: Alice Munro’s “Tricks” and Waiting in Literature

I am in the midst of an anticipating season. My first book comes out in a month; my second baby will be born in a little over two. I’m finding that in terms of productivity right now I’m pretty useless. Most of the work for the book is done, and most of the work for the baby is yet to come, but somehow waiting is taking up all of my time.

Narratives that devote space to the state of waiting interest me. In fiction, unlike in life, time is manipulable: the writer has the freedom to compress or expand it on the page, to choose where the story lingers. Fiction doesn’t have to spend time on the anticipation of events, rather than on events themselves; when it does, it’s so the writer can plumb different kinds of depths. The state of suspension and the reflections it enables can change characters, and readers, as much as—more than—the anticipated events themselves. Waiting for Godot is perhaps the classic example, but there are plenty of others. The Death of Ivan Ilyich isn’t about death, but about Ilyich’s reactions to death’s approach. Donna Tartt’s The Secret History isn’t about a group’s murder of their friend so much as it is about the group’s contemplation and planning of murder, and then the wait to see if they’ll be found out.

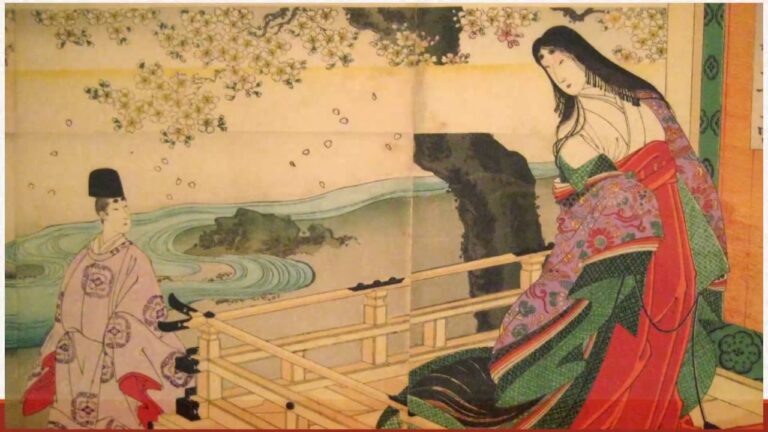

There’s an Alice Munro story I love, “Tricks,” from her collection Runaway, that does a masterful job immersing the reader in anticipation’s effects. Robin, the main character, is twenty-six and has so far led a life that has mostly consisted of waiting. She works as a nurse in a small Canadian town, where she spends much of her time caring for and catering to the querulous demands of her thirty-year-old invalid sister. We learn partway through the story that while she’s very lovely, “Robin had never had a lover, or even a boyfriend. How had this happened, or not happened? She did not know […] A reason might have been that she had not given the matter enough attention, soon enough.” No phase or aspect of her life so far has seemed to merit this kind of attention, because none of it has seemed quite real to her—quite good enough to be real. High school and her nursing training and now her long stretches of devotion to a sister she can’t stand have all struck her as so disappointing and small that they must be only preludes to the real thing.

Robin’s only glimpses of the real, as she sees it, are her once-a-year trips on the train, alone, to see a Shakespeare play in Stratford. She’s been taking these trips for five years when we meet her, and the one-day ritual has come to structure her life:

…those few hours filled her with an assurance that the life she was going back to, which seemed so makeshift and unsatisfactory, was only temporary and could easily be put up with. And there was a radiance behind it, behind that life, behind everything, expressed by the sunlight seen through the train windows. The sunlight and long shadows on the summer fields, like the remains of the play in her head.

I love this passage; this belief that everyday surroundings are only obscuring some deeper kind of truth feels so recognizable to me. I felt this way all the time when I was a kid—that there must be more coming—and I think any state of prolonged waiting is a little like this, too. Whatever the impending event is (even if we don’t really know what it is), it overshadows the present facts, makes them seem flimsy and inconsequential, barely worth considering.

Because this is a story, the dramatic promise that Robin’s plays seem to be making doesn’t just hang there unanswered: one year, after seeing Antony and Cleopatra, she meets a magnetic foreigner, and the world seems to open up in just the way she’s always expected. Preening in front of the mirror in the ladies’ room after the play, she loses her purse, and while she’s walking around trying to figure out how she’ll get home, she bumps into a man named Danilo Adzic—an émigré from Montenegro, out walking his dog. He gives her money for the train, makes her dinner while they wait, and fires her whole self and imagination. By the time her train is due she’s sure the course of her life has changed:

“I think it is important that we have met,” he said. “I think so. Do you think so?”

“Yes. Yes.”

He slid his hands under her arms to hold her closer, around the waist, and they

kissed again and again […]

“We will not write letters, letters are not a good idea. We will just remember each other and next summer we will meet. You don’t have to let me know, just come. If you still feel the same, you will just come.”

The “important” event, so long promised, has occurred. They have made explicit its importance, and decided what the next step will be.

So begins a different kind of anticipation in Robin’s life. The transition to this new wait—the wait for a specific development, instead of a dreamy amorphous future—seems to me the key to this story. The first, vaguer kind of anticipation is mostly a passive state, demanding nothing of Robin, really. It’s a lens through which she can look at her life so that she can better endure it. The second kind, though, is an active process. Robin goes back home, tells her sister nothing of what has happened, and begins spending all of her time learning about Montenegro. Reading about its history, its geography—trying to learn Danilo himself. The idea of him, and of herself with him, is something she curates as she moves through her daily life:

She had something now to carry around with her all the time. She was aware of a shine

on herself, on her body, on her voice and all her doings. It made her walk differently and smile for no reason and treat the patients with uncommon tenderness.

The deepest part of Robin’s self is constantly occupied with a job that has nothing to do with the tasks she completes in a day. She is tending the memory of being with Danilo, and building an imagined future with him, and waiting for the appointment they’ve set for that future’s arrival. This, I think, is the kind of waiting that really consumes.

I don’t want to give too much away about the story’s devastating ending—suffice it to say that the future Robin has dreamed up misses her, and that the importance of Shakespeare’s plays (with all their missed chances, and theatrical errors, and dramatic doublings) to the story’s architecture turns out to be deep. Waiting is perhaps mostly about hope—even when the coming event is a dreaded one, a corollary hope attends the fear, a hope that maybe the event will somehow change course—and Munro reminds us that hope carries risks. That imagined futures can leave us bereft if they don’t arrive, or arrive differently than we expected.

Still, I’m not sure what else there is to do. The piece of myself that’s thinking about the months to come as I move through my day—as I take care of my first daughter, as I keep trying to write new things—is not a piece I know how to turn off. And it’s busy.