All Rise for the Story: Writing Lessons at Jury Duty

We tell ourselves stories in order to live…We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the “ideas” with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience. — Joan Didion, The White Album

There seemed no crueler fate last November than to be drawn as a potential juror from a roomful of two hundred New Yorkers—all of us cold, sleepy but most of all impatient to return to our daily routines. All morning I waited to hear my name, certain with dread, panicking already about the hours the civic duty would surely engulf. With two jobs, my schedule was already rowdy.

Taking turns, we jurors testified to the details of our lives: occupation, birthplace, highest level of education, whether we’d been victims of violent crimes. Could we be impartial? Would we be fair? We were born in London, Scotland, the Philippines, living in Manhattan’s Harlem, Greenwich Village, Upper West Side. We were clinical technicians, line cooks, and energy traders who had escaped rape in Central Park, were mugged at knifepoint, had been in car accidents. We held a doctorate’s in Physics, two masters in Public Relations. Characters were taking shape. Next to me, a good-looking man in a navy suit blew loud, exasperated sighs. I edged away from his line of breath and lack of curiosity.

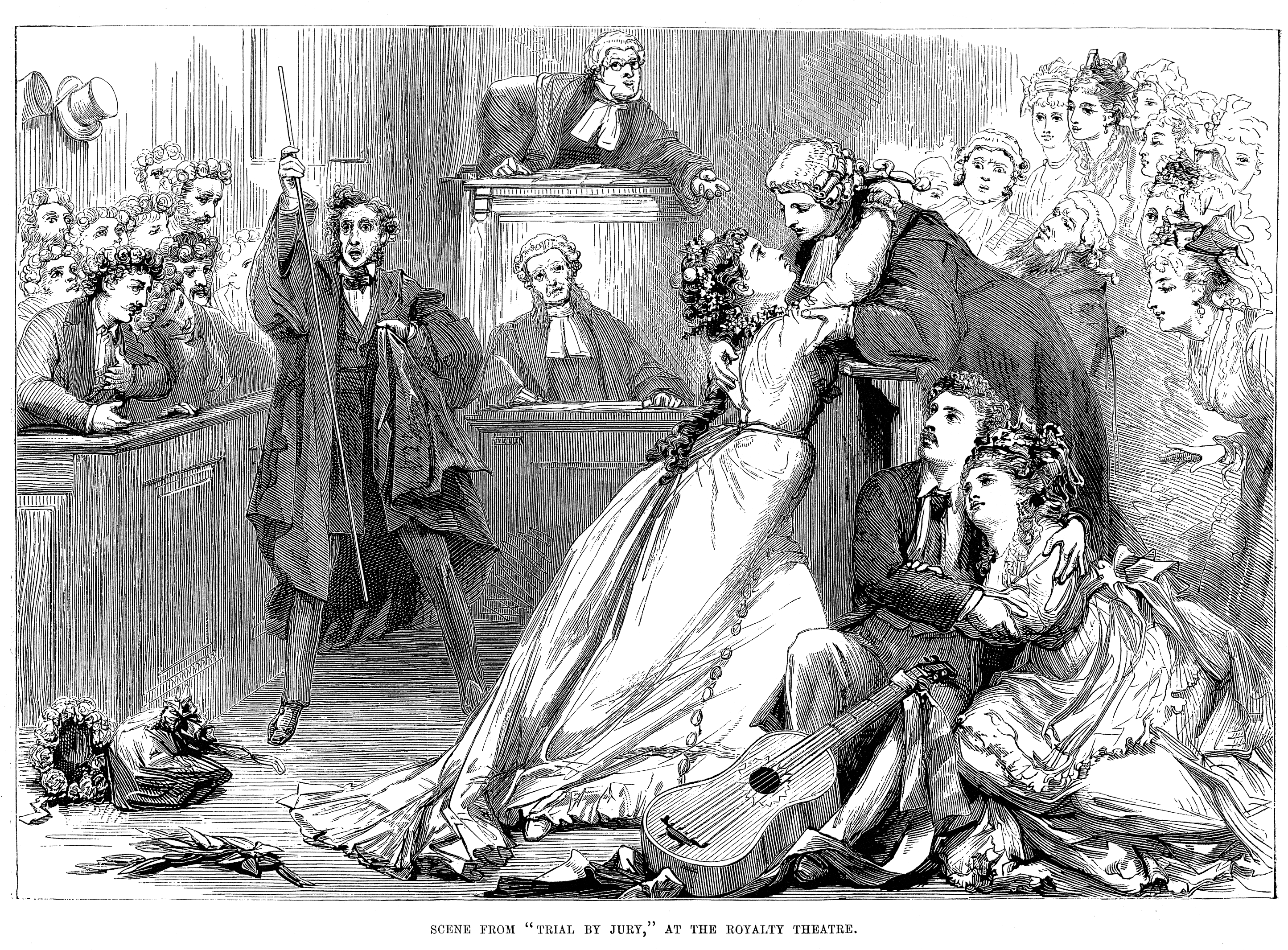

Sure enough I was summoned, screened, and appointed Juror #12 on a twelve-person jury. With what I thought was the unlucky lottery behind me, my four days of service turned out to be fabulous. The ritualistic tedium of the court fascinated me, the stenographer’s verbatim recordings, the sanctimony of due process. But at the root of it, I felt energized and encouraged by the weight and necessity of storytelling in the judicial process. The judge inquired with interest after a juror’s path from law to running a tree nursery, dismissed another who grew up hearing his nurse mother’s accounts of trauma in the ER. But it was the trial itself that served as a real lesson in storytelling.

With the DA’s opening remarks the details of the case emerged: minor fender bender involving an intoxicated defendant and a yellow cab driver. The Defendant, after an attempt to pay off the Cabbie, runs away when Cabbie refuses money and calls the police.

It seemed like a simple enough story, one that might not take so long to resolve after all.

It quickly grew complicated.

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury,” the District Attorney trilled from the rail. “After hearing the details of the case, you will find that the Defendant was inebriated. After hearing the Cabbie’s testimony, you will agree that the Defendant…”

On and on she went like this. We would see. We would realize. And we would convict. Her commands fell on us like a gavel.

Around me, arms began to cross, pupils glazed, eyebrows arched. I could not blame my fellow jurors. How many times have I read a story that tried too hard to convince? I was especially guilty of it when I began writing essays, veering from my intention of an intimate, confiding voice toward a didactic and pestering one.

In “Portrait of the Essay as a Warm Body,” Cynthia Ozick writes, “And what is oddest about the essay’s power to lure us into its lair is how it goes about this work. We feel it when a political journalist comes after us with a point of view — we feel it the way the cat is wary of the dog. A polemic is a herald, complete with feathered hat and trumpet. A tract can be a trap…What is indisputable is that all of these are more or less in the position of a lepidopterist with his net: they mean to catch and skewer.”

Readers pull away the moment they detect they are being told how to think, feel, or act. It was no different here: this jury wanted to reach its own conclusions.

The damage done by the DA’s intro was significant. I might have forgiven her desperate urgings, but her remaining arguments were so poorly constructed, rife with gratuitous detail and awkwardly delivered. I imagined her in her office sifting through the minutiae of the case, choosing what to include, what to leave out. A trial lawyer, like a writer, must be skilled in the creation and discernment of a story. Our DA hadn’t edited enough—what did the cold temperature or the fact it was a Saturday night, details she repeatedly emphasized, have anything to do with the incident?

As the DA closed her version of events and the defense attorney began his, I had the off-hand thought that trials are like story slams or an episode of reality competition. I imagined a vogue-off. The intention of the lawyer to win our favor is no secret here—buy my story, don’t buy theirs—, but the telling counts. Respect the listener. Respect form and structure. Don’t pander so artlessly. If the facts are dubious, if witnesses and victims give contradictory interpretations (a quandary called the Rashomon Effect for Akira Kurosawa’s classic 1950 film), it may well be the style of storytelling that ultimately sways jurors. While the DA was heavy-handed and contrived, the defense attorney employed a light, restrained manner. Each of his words, deliberately and calmly delivered, had the feeling of the utmost necessity. His approach reminded me of John McPhee’s gentle yet rigorous style of literary journalism.

In a perfect case of “Show, Don’t Tell” (a rule this writer loves to hate), see Exhibit A. In his cross-examination of the Cabbie the defense attorney had only one request: the Cabbie to come stand next to him. The Cabbie, confused, did as he was asked. “We’re about the same size, aren’t we?” the defense attorney said, facing the jury. He then approached his client, the Defendant, and asked him to do the same. The Defendant, broad and muscular, loomed almost two feet taller than his attorney. “Ladies and gentlemen, I just want to give you this visual. Thank you.”

Expertly, without another word, he planted doubt in our minds, a murk that clouded the testimony we’d just heard from the Cabbie of chasing the Defendant through a subway entrance and physically pulling him back up to the street where he handed him over to the authorities. Ambiguity, omission, mystery, implicated meaning—these are powerful ways to tell a story. The guy knew what he was doing.

We all know well the oath taken in a courtroom, the witness’ promise to tell “the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth,” words dramatized in film, television, stage, and literature for decades. But what if facts, or truth, on their own do not resonate? Studies show that whether we’re told a story or not, our brains instinctively build a story around a set of facts. It’s how we make sense of a set of complicated facts. It’s how we impose order on chaos. Because under the court system’s veneer of civilized order, it’s chaos and the elasticity of factual accuracy that really governs here. So how to tell the truth?