An Interview with writer Yu-Mei Balasingamchow

Yu-Mei Balasingamchow is a fiction and nonfiction writer from Singapore. Her stories appear in the anthologies From the Belly of the Cat (2009) and Let’s Tell This Story Properly: Commonwealth Short Story Prize Anthology (2015), as well as in the journal Mänoa. Her nonfiction work includes Singapore: A Biography (2009), co-authored with Mark Ravinder Frost and commissioned by the National Museum of Singapore. Balasingamchow participated in the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program (IWP), a ten-week annual residency for writers from around the world, in fall 2015.

Xin Tian: Tell me about the residency program.

Yu-Mei Balasingamchow: IWP is very contained—it’s ten weeks, you live on campus together, then everyone goes home. You’re always running into each other in the same place. These experiences help because they’re small and short—you go there, it’s really stimulating, take it or leave it, and then it will never happen again.

I could hear myself think so clearly. You start giving yourself reasons to say yes, rather than no, about what you want to write. Being taken out of the place where you usually write and being placed in this foreign environment is quite idyllic. It doesn’t ask very much of you except just to be there.

IWP asks that you do one public reading at the Shambaugh House or at the Prairie Lights bookstore in town. Some residents read from their native languages, or from newly translated pieces that they worked on with students at the university’s MFA in Literary Translation.

We were also involved in an undergraduate class, International Literature Today (taught by Christopher Merrill and Natasa Durovicova), where students read and ask questions about residents’ work. A few of us spoke to high school creative writing students at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, and at a class at Bard Early College New Orleans, where there are college prep classes for public high school students. In DC, I visited an AP Lit high school class through a PEN American Center school outreach program.

X: What were you working on then?

YB: I wrote an essay there, started a short story, started revising one novel, and did a lot of research for another novel. The second novel has some scenes set in the US, so being in Iowa was a good opportunity to get the research done. I got to interview some university experts in a field which I don’t want to reveal right now.

X: What’s the international response to your work like?

YB: “International response” is a very glamorous term for “what do people outside Singapore think?” The Turkish resident, Birgül Oğuz, said to me early on, “You know, I read your story ‘Grandmother’ and connected with it.” I’d just arrived, everything was still very new, and I thought, “Wow, someone’s read my story and it made sense to her, even though she may not be familiar with Singapore!”

In Singapore, we have lots of hang-ups about whether people will understand our stories or our Singlish. Nobody ever came up to me and said, “I didn’t understand the Singlish in your story.” Not a single person said that.

People have lots of postcolonial assumptions about whether or not stories can travel internationally. I think the “foreign market” is different from the “foreign reader.”

X: How would you define Singapore literature to a US audience?

YB: Singapore literature is literature written in and about Singapore, or by a Singaporean. It’s very simple.

That said, I always told people at IWP that I was speaking only about English-language Singapore literature because I cannot access the Chinese, Malay, and Tamil works much as so little is translated into English. I’m always aware that I’m speaking from one narrow perspective. A Singapore writer who writes in Chinese might come to IWP this year and tell a completely different story about the Chinese-language writing and reading scene.

X: What do you think Singapore literature can gain by its writers being exposed to international markets and writing by purposefully going abroad, such as you did?

YB: It was a reminder for me that there are a lot of people in the world who read outside the North American market, and that there are many ways to write and many things you can write. There was a 65-year-old Cuban writer, Margarita Mateo Palmer, who has been writing for most of her life, lived through the Socialist era and all and moved in her own writing from criticism and essays, to fiction. She’s also aware that she belongs to this long tradition of Cuban literature. We also had writers on the other end of the spectrum who were younger, haven’t been published that much and are still working out how they want to write.

Everyone was trying different things. I think it’s a good reminder that there’s still a lot of art being created without the mindset of “Will this sell in New York or London?”

X: How would you describe your style of writing?

YB: Realist, in the sense that I’m preoccupied with the idea of conveying a Singapore that does exist. Getting authentic detail down is important to me. If I’m writing about Ang Mo Kio Avenue Something, I want to know how long it is, even if it doesn’t go into the story. The details matter.

I don’t want to write about a purely imaginative—in the sense of, say, mermaids—place. Not that there’s anything wrong with writing about mermaids or things which don’t exist, but for me, right now, it’s the real, contemporary world I want to put in my fiction.

It seems important to me to communicate the Singapores that are really here, partly because of the literary culture we had for many years, in which we didn’t have many representations of ourselves. Knowing that you’re from a very small country with few writers makes you all the more want to prove that you exist. To write this thing, and to say, “Life is really like this.”

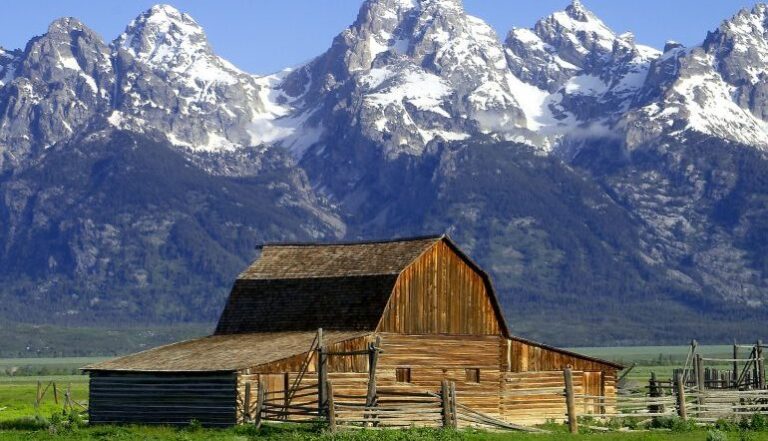

Photograph by Deanna Ng