Artists on the Outskirts in Olive Kitteridge and Little Fires Everywhere

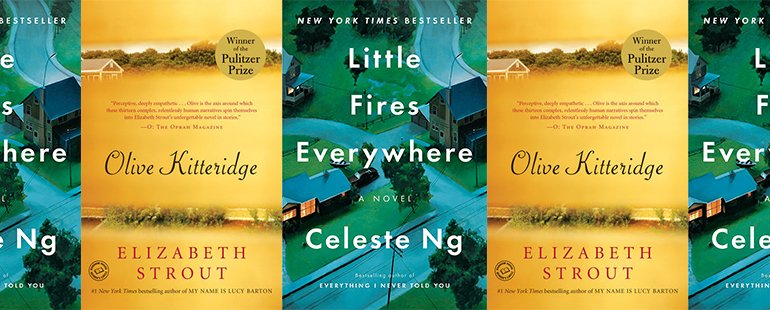

This summer I’ve been reading novels about insular towns. Setting a story in a place where there are unspoken rules of decorum, a neighborhood that seems homogenous to outsiders, or a small town where everyone knows each other is a way to create conflict immediately. Intuitively, the reader knows that surfaces aren’t as they seem, that apparently harmonious interactions between people usually mask the more complicated dynamics underneath. Two novels about tight-knit communities, Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge and Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere, immerse readers in masterfully constructed plots driven by secrets large and small. Narrative tension arises as the reader slowly disentangles the way things are from the way things seem. Though the books are very different in tone and structure, both are interested in the way desire, individuality, and moral intuition are sublimated in communities that have a lot of rules. Strout and Ng (guest editor of Ploughshares’s Summer issue, out today) are interested in characters who live on the outskirts, who reflect the community back to itself, who attract interest even as they inspire unease. Each book introduces readers to an artist on the fringes—in both, an enigmatic, unmarried woman—who plays a variety of roles in the collective imagination, from moral compass to rule-breaker, from foil to mirror.

In Olive Kitteridge, the artist is Angie O’Meara, who plays piano at the town’s cocktail lounge. Strout describes Angie’s relationship to the community in the opening paragraph of the story about her: “the townspeople of Crosby, Maine, had for many years now taken into their lives the cocktail music and presence of Angie O’Meara.” The relationship between townspeople and artist is intimate, personal—the two entities aren’t just adjacent, but intertwined. Angie is familiar to them, and, at the same time, mysterious: her private sufferings are “considered nobody’s business.” Over the course of the story we learn the basic facts of Angie’s life: she “lived in a rented room,” and “did not own a car.” She drinks heavily; she memorizes customers’ favorite songs; she’s had a decades-long affair with a local politician. Angie is also the daughter of a mother who “had taken money from men,” who in the present lives in a nursing home.

Over the course of twelve pages, “The Piano Player” unspools the disappointments and triumphs of Angie’s life. About her affair, she reflects: “people might call her life with Malcolm pathetic.” But Strout portrays her with humanity and integrity. The action of the story is mostly in the past. Strout tells the story of a naturally talented pianist kept home by her mother’s insistence that she be “Mommy’s girl.” In the story’s present-day timeline, an old flame, Simon, surprises Angie at work to tell her that he’s pitied her for years. Simon was once the pianist at the lounge, but was rejected from music school and became a real estate lawyer in Boston. After he leaves, Angie gets back to the piano:

She didn’t know what she played, couldn’t have said, but she was inside the music, and the lights on the Christmas tree were bright and seemed far away. Inside the music like this, she understood many things. She understood that Simon was a disappointed man if he needed, at this age, to tell her he had pitied her for many years [ . . . ] she understood that this form of comfort was true for many people [ . . . ] but it was thin milk.

Simon’s nastiness to her, she reflects, is about him, not her, and she concludes with the cutting observation: “[It] could not change that you had wanted to be a concert pianist and ended up a real estate lawyer, that you had married a woman and stayed married to her for thirty years, when she did not ever find you lovely in bed.”

The story is full of these sorts of character observations. When Angie sees Henry Kitteridge, who reappears in most of the stories, it’s “like moving into a warm pocket of air.” These observations seem to stem from an openness in Angie’s own personality—openness that alternately manifests throughout her life as naïveté and wisdom. Strout describes her face as one that “revealed itself too clearly in a kind of simple expectancy.” Strangers find “the open gaze of her blue eyes” unsettling. It’s a gaze that searches and reveals, even if the observer herself is flawed, full of her own private sorrows and petty cruelties. She understands the randomness of life and the futility of hierarchies: “[F]or Angie time was as big and round as the sky, and to try to make sense of it was like trying to make sense of music and God and why the ocean was deep. Long ago Angie had known not to try to make sense of these things, the way other people tried to do.” What Angie prioritizes instead of making sense of things is honoring emotion, which is central to her art. This is part of why she continues as a pianist while Simon becomes a real estate lawyer: “deep in her heart she had known even then that his playing lacked—well, feeling.” Angie, with her drinking and her rented room and long affair, has not lived, by the standards of her small town, a sensible life. But she has feelings—and so does her art. It’s Simon’s life, full of suppressed feeling, that Strout suggests is the failure.

In Little Fires Everywhere, Ng also explores the friction between feelings and rules. Like Simon and Angie, who begin with similar goals but whose lives diverge over the course of decades, Ng also positions an artist and non-artist in tension with one another. Elena Richardson, who writes competent but unexciting pieces for the local paper, rents an apartment to Mia Warren, a photographer who’s often on the road. The two women live across town from one another. Elena has all the trappings of conventional success: a big house, four children, a successful husband, and community clout. Mia is unmarried, also a mother, owns almost nothing, and is single-mindedly focused on her art. The two women become entangled—through their children, and on opposing sides of a controversial court case in the neighborhood.

The language of entanglement Ng uses when first describing the families’ involvement with one another is, like Strout’s description of Angie and the townspeople, visceral and intense: “[A]s the weeks went on it worried Mia a little, the influence the Richardsons seemed to have over Pearl, the way they seemed to have absorbed her into their lives—or vice versa.” The fascination seems, at first, to be one of opposites. While Mia and her daughter Pearl move whenever Mia needs new inspiration for her photographs, Elena and her family live according to what’s sensible and sanctioned. Of Elena, Ng writes: “She had been brought up to follow rules, to believe that the proper functioning of the world depended on her compliance.” She builds “a good life, the kind of life she wanted, the kind of life everyone wanted. Now here was this Mia, a completely different kind of woman leading a completely different life, who seemed to make her own rules with no apologies.” Like Strout’s Angie and the Crosby townspeople, Mia makes Elena “uneasy.” And Elena’s reaction to this uneasiness is to remind Mia of her status in the community’s hierarchy: Elena hires Mia to clean her house.

As the novel unfolds, the reader comes to understand that Elena, too, had fiery passions when she was young: for a man she didn’t marry, for a more hard-hitting brand of journalism, for social justice. But rather than follow her unruly feelings, as Mia does, Elena suppresses them. The lives of Strout’s Simon and Angie diverge at the point when he gives up the piano and she doesn’t. Ng’s Mia and Elena diverge when Mia decides to live by her own rules—based mostly on feeling and strong moral impulse—and Elena chooses to abide by those of the external world and the insular neighborhood in which she grew up.

There is a cost, of course, to both ways of living. Mia’s nomadic tendencies leave her daughter feeling rootless, and she’s been out of touch with her own parents for years. But the novel positions Elena’s hubris—her certainty that she knows how to live a correct life, if not one that’s right—as more dangerous. In Olive Kitteridge, Angie ruminates on Simon’s true nature when he dredges up a secret from her past and tries to make her feel lesser. In Little Fires Everywhere, Elena does a similar maneuver, and Mia voices her observations:

Now it was her turn to study Mrs. Richardson, as if the key to understanding her were coded into her face. “It terrifies you. That you missed out on something. That you gave up something you didn’t know you wanted.” A sharp, pitying smile pinched the corners of her lips. ‘What was it? Was it a boy? Was it a vocation? Or was it a whole life?’

As Angie pities Simon, Mia pities Elena. This is one of the roles, it seems, of the artist pitied by a conventional community: to voice the truth about people, the mistakes they won’t admit to themselves. It’s not that Mia or Elena don’t make mistakes, it’s that they have, as Joan Didion put it in a 1961 essay on character, “the courage of their mistakes . . . the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s own life.” What they avoid—mostly—is what Didion calls “alienation from self.” In small communities that in some ways depend on this alienation, the artist on the outskirts is a reminder of how dangerous it is to turn one’s back on self-knowledge, even if a community—and its rules—feels like home.