A Valentine to the Best American Poetry 1993

Before social media helped readers discover poetry, the world seemed smaller. In the early 90s, when I was a preteen starting to figure out that not all great poets were dead, I had little to go on.

Before social media helped readers discover poetry, the world seemed smaller. In the early 90s, when I was a preteen starting to figure out that not all great poets were dead, I had little to go on.

If there is an equivalent of the artist’s statement in poetry, it’s the ars poetica. Latin for “the art of poetry,” the ars poetica shows up as early as Horace, in 19 BC, and most poets since, it seems, have written at least one.

Many of us who love poetry think of metaphor as being somewhere in its DNA. Without metaphors, somehow, it seems, poetry would not be itself.

I’ve been wired since girlhood, by factors ranging from my Catholic upbringing to low self-esteem, to shrink, to make myself smaller, to avoid bringing attention to myself. Perhaps my comfort with small poems has underpinnings I should interrogate.

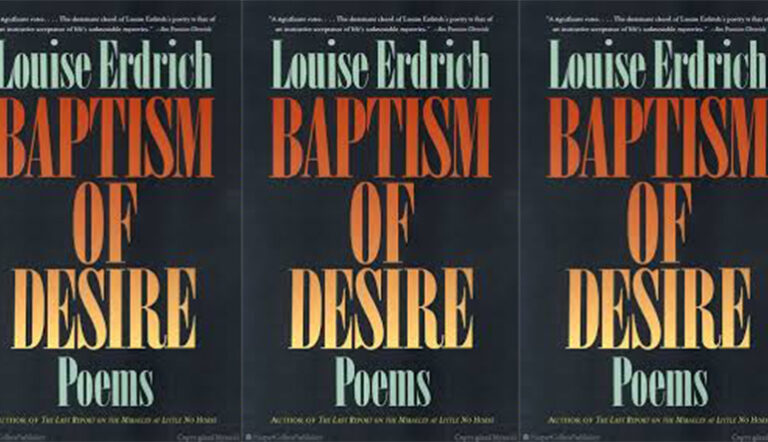

While Louise Erdrich’s fiction investigates the devastating impact that Catholic missionaries had on traditional Ojibwe practices, her poetry collection, Baptism of Desire, investigates a soul that exists in the hybrid space where the two spiritual forces meet.

Whatever the case, it’s certainly true that for most of my reading life, it never occurred to me that poetry could be anything other than beautiful.

Mary Jo Bang’s raucous translation of Inferno, published in 2013, tries to bring us as close as she can to the intrigue of Florence in the 14th century.

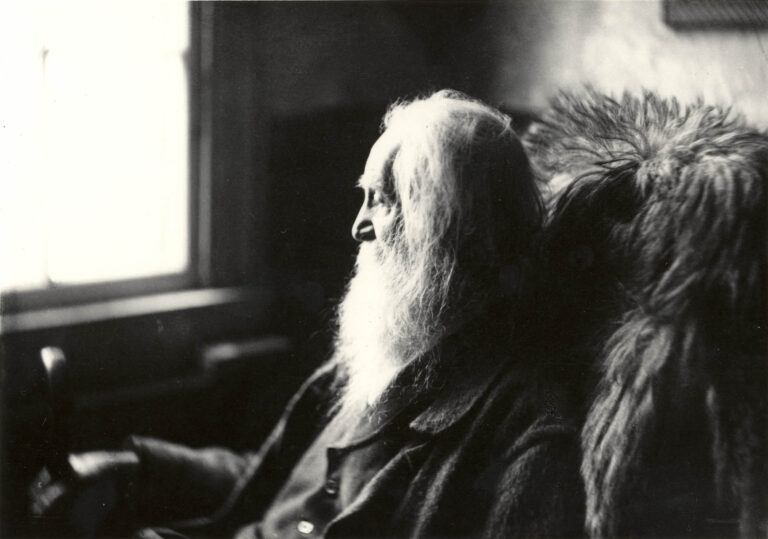

I saw all the things we consider “Whitmanesque”: the energy, the exuberance, the empathy. And one thing that my mother’s serene portrait had not prepared me for—the eroticism.

Perhaps in times like these, when the work of making sense of the world around us gets harder, we need poetry that points toward that difficulty—and that makes that work worthwhile.

No products in the cart.